This is one section of Modernizing Behavioral Health Systems: A Resource for States. See the full resource guide.

Delivery systems can avail themselves of a comprehensive array of evidence-based services and models that address the complexities of mental illness and addiction across an individual’s lifespan. Still, access to these approaches is more rare than not and is heavily influenced by inequities.

There is a growing consensus on the significance of adopting a person-centered recovery-oriented approach deeply rooted in the community, reducing reliance on acute care and institutional settings. States are at the forefront of moving the needle toward increasing access to high-quality evidence-based behavioral health services and supports.

The following section highlights essential services in alignment with SAMHSA’s vision for achieving a “good and modern” behavioral health system, the framework and principles of which still hold and can guide current modernization efforts. It includes examples from various states organized by the framework buckets: integrated primary and behavioral health care, crisis continuum of care, in-home and in-community based, and out-of-home and community.

Integrated Primary and Behavioral Health Care

A modern behavioral health system of care is fully integrated into the continuum of health care services, including primary and specialty care settings, and extends into homes and communities to ensure holistic and coordinated support. Foundational work in primary care shows promise for early identification, treatment, and referral to specialty mental health and addiction services. Achieving effective behavioral health integration can be customized through various care delivery models, adapting the implementation to specific patient demographics and local factors. While integrated care hinges on routine screening and assessment, several evidence-based models include a comprehensive team-based and coordinated approach that provide early identification, intervention, and referral to specialty services as indicated.

States have a range of tools and policy levers at their disposal to build capacity for integrated behavioral health approaches. Administrative simplification efforts can streamline processes and reduce bureaucratic barriers, making it easier for providers to coordinate care. Payment and delivery reform strategies can incentivize integrated care models by aligning payment structures and encouraging collaboration between primary care and behavioral health providers. Additionally, the establishment of joint licensure programs can facilitate integrated provider settings by bringing professionals from different disciplines together, promoting a unified and coordinated approach to patient care.

Psychiatric Collaborative Care Model

The Psychiatric Collaborative Care Model (CoCM) is an integrated care intervention with the most robust evidence for high care value and improving outcomes related to depression and anxiety in primary care settings, as well as patient satisfaction, when compared to usual care (see the Institute for Clinical and Economic Review report “Behavioral Health Integration” and the Milliman report “Potential Economic Impact of Integrated Medical-Behavioral Healthcare”).

States have taken a number of strategies to support the adoption of the CoCM through policy initiatives and reimbursement strategies. States such as Texas, Wyoming, and New Jersey are adopting Medicaid reimbursement of collaborative care services and are addressing capacity to transition to CoCM. New York does this by offering provider start-up technical support, training, and enhanced rates that resulted in more than 14,200 Medicaid patients receiving collaborative care in 2022. North Carolina’s comprehensive behavioral health approach included efforts to increase uptake of CoCM through additional training and practice supports and Medicaid rate increases to 120% of Medicare rates for behavioral health providers.

Integration of Substance Use Services and Supports

States can align long siloed approaches to primary care, mental health, and substance use services through integration efforts. People with substance use disorder are more likely than those without to have co-occurring mental illness and commonly develop physical conditions that exacerbate symptoms. Yet, serious gaps exist in treatment for co-occurring disorders (COD). People with COD are significantly more likely to be arrested, with a disproportionate impact on women and Black adults.

In Oregon, House Bill 2086 (2021) directs the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) to reimburse for COD treatment services at an enhanced Medicaid rate based on clinical complexity, provide start-up funding for programs that provide integrated COD treatment, and study reimbursement rates. The OHA has worked with community partners to establish the integrated COD program that includes training, a single payment model for integrated treatment services, and a specialty credential for providers.

The New Hampshire Governor’s Commission on Alcohol and Other Drugs’ updated action plan includes a multi-pronged approach to increasing access to interventions for people with co-occurring disorders with a special focus on youth. The commission was created in the New Hampshire Legislature in 2000 (NH RSA Chapter 12-J), which established the Alcohol Fund, directing a part of proceed from sales of alcohol to prevention, harm reduction treatment, and recovery services. An action plan dashboard tracks targets.

In West Virginia, the Department of Health and Human Resources (DHHR) received a $3 million grant from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to expand its existing Drug Free Mom and Baby Model, which provides coordinated care for pregnant individuals with a history of opioid use. Services are provided by community health workers, peers, and medical providers, including OB-GYNs for up to one year postpartum. Services include medication-assisted treatment.

Additional Resources

- The University of Washington’s AIMS Center provides multiple resources and models, including linkages to the latest CMS guidance on Collaborative Care Model G-codes and billing.

- The “HHS Roadmap for Behavioral Health Integration” summarizes key elements of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services’ development of policy solutions to enhance behavioral health integration.

Behavioral Health Integration for Children and Youth

Behavioral health integration for children and youth involves their unique needs, which encompass developmental milestones, age-appropriate communication, and specialized health care services tailored to their growth and well-being. Best-practice integrated behavioral health care approaches for children and youth depend on the regular use of screenings, assessments, and referrals to ensure they have access to the complete spectrum of behavioral health services as mandated by the Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) benefit in Medicaid (see the “Center for Medicaid and CHIP Services Information Bulletin”).

Models such as Integrated Care for Kids (InCK) and Maternal Opioid Misuse (MOM) offer states opportunities to integrate behavioral health care for individuals with complex needs that span health care and social service systems. North Carolina’s InCK program, led by Duke University and the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, brings together partners from Medicaid, behavioral health, child welfare, juvenile justice, education, Title V, mobile crisis, and more to coordinate care and address the health and social needs of children in five counties. By promoting coordination of clinical care and the integration of essential services, such models hold the potential to enhance the quality of care and lower costs for those affected, such as pregnant and postpartum Medicaid beneficiaries with opioid use disorder. Insights from the first-year evaluation of the CMS MOM model highlight both the challenges encountered during implementation and the benefits of various forms of support, such as peer recovery services. This state-driven innovation program in seven states (Colorado, Indiana, Maine, New Hampshire, Tennessee, Texas, and West Virginia) aims to enhance the integration of maternity care with behavioral health and opioid use disorder treatment.

In Massachusetts, the state’s Children’s Behavioral Health Initiative (CBHI) provides a continuum of care for children, youth, and families in home- and community-based settings, stemming from a class-action lawsuit filed on behalf of the state’s population of children with severe emotional disturbances. CBHI began in 2009 as an expansion of the state Medicaid program, and its services are covered by MassHealth for MassHealth members under the age of 21. The suite of services includes in-home behavioral health services, family support and training, intensive care coordination, therapeutic mentoring, and mobile crisis intervention services. The program requires primary care providers to conduct behavioral health screenings and standardizes the Child and Adolescent Strengths and Needs (CANS) assessment tool for all state clinicians. Outcomes and progress are measured through CANS assessments every 180 days (six months) or when the clinical presentation changes.

Other approaches include:

- Healthy Steps is a comprehensive pediatric primary care program that integrates behavioral health support into routine well-child visits. It focuses on early detection, assessment, and intervention for developmental and behavioral concerns, promoting healthy child development through a collaborative approach involving pediatricians and mental health professionals. It is operational across 231 hospitals and medical practice sites in the U.S. New York and New Jersey have expanded state appropriation funding to expand access to Healthy Steps as a critical piece of their multi-pronged behavioral health strategy. State Medicaid authorities can use the Healthy Steps Return on Investment tools to examine the program’s impact on the state budget and outcomes.

- The Nurse-Family Partnership (NFP) pairs registered nurses with low-income first-time mothers during pregnancy and continues with regular home visits until the child’s second birthday. This evidence-based model emphasizes maternal and child health, providing support, education, and guidance to promote positive parenting practices and improve child outcomes. NFP is being used in communities in 40 states. As noted in NASHP’s “State Medicaid Innovations to Support Home Visits” blog post, Alabama extended its NFP program statewide as a targeted case management benefit under its Medicaid program.

- Help Me Grow is a system designed to identify developmental and behavioral concerns in young children and connect families with appropriate services. It acts as a centralized hub for information and resources, ensuring that children receive timely and tailored interventions to address their specific needs, supporting their healthy growth and development. In 2017, the Ohio Senate passed Bill 332 to establish Help Me Grow as Ohio’s evidenced-based parent support program. Additionally, the legislation required Help Me Grow to use only evidence-based, innovative, or promising home-visiting models to improve maternal and child health, prevent child abuse and neglect, encourage positive parenting, and promote child development and school readiness. In Alabama, state funds support implementation in all 67 counties through regional partnerships with local agencies and centralized telephone access. In Florida, a Florida State University Help Me Grow study found that every dollar invested in the program returns approximately $7.62 in total economic output.

- TEAM UP for Children is a collaborative care model that combines pediatric primary care with on-site mental health services for children and adolescents across the child developmental years. This approach brings together a team of pediatricians, child psychiatrists, and behavioral health providers to offer comprehensive care, ensuring that children receive timely assessment, treatment, and support for both physical and mental health needs. A Massachusetts-based study of TeamUP on the impact in underserved communities led to the inclusion of TeamUP in the state’s “Roadmap for Behavioral Health Reform” and the provision of preventive behavioral health services to MassHealth members under 21 years old without requiring a diagnosis.

Additional Resources

- District of Columbia: 0–5 is a developmentally based system for diagnosing mental health and developmental disorders in infants and toddlers. DC: 0–5 Manual and Training. Integrating DC:0-5 into State Policy and Systems

- The following resources on the Nurse Family Partnership model provide reference information that can aid in planning and implementation efforts:

- The Healthy Steps Evidence Summary provides valuable insights into the program’s impact and effectiveness.

- The Child Health and Development Institute includes resources and training on Adolescent Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral for Treatment (A-SBIRT), an evidenced based practice designed to engage youth and families in detecting substance us risk.

Psychiatry Consultation-Liaison Programs

A well-replicated approach to specialty consultation, Project ECHO has been adapted for behavioral health with the goal of increasing primary care capacity to deliver behavioral health care to patients within their own practices. It provides education and training for screening an assessment of behavioral health needs. It is worth noting that 2023 CMS guidance changes allow federal matching funds for interprofessional consultations. States can submit amendments or waivers to implement this, making it easier to support the ability of primary care providers to consult with specialists such as psychiatrists or psychologists when treating patients with behavioral health needs.

The state of Ohio has invested in multiple Ohio Project ECHO efforts across its system to address the needs of adults and children, including the Ohio Systems of Care (SOC) Project ECHO for Youth Involved with Multiple Systems. Since its inception, the Ohio Systems of Care Project ECHO have held 172 sessions, with 1,235 unique participants participating nearly 7,000 times. Survey results indicate that 73 percent of participants reported directly applying knowledge from the ECHO sessions into their practice.

Nebraska dedicates opioid crisis grant funding to Project ECHO programs tailored for both adults and children, with a specific focus on Project ECHO addiction treatment within pediatric health care settings.

Chronic pediatric psychiatry shortages spurred national uptake of psychiatric consultation models, including Massachusetts Child Psychiatry Access Program (MCPAP), now used in over 40 states, and the Pediatric Mental Health Care Access program run by the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration.

In Massachusetts, MCPAP, funded primarily through a state appropriation of over $4.6 million a year to the behavioral health authority, ensures the availability of psychiatric consultation to all primary care clinicians in the state regardless of insurance status of the youth and their family. MCPAP is required to submit encounter data to the Massachusetts House and Senate Ways and Means Committee on the number of consultations, face-to-face consultations, and referrals made to specialists on behalf of children with behavioral health needs, as well as an overview of MCPAP’s care coordination efforts and recommendations for services. The most recent program recommendations and data focused on the need for more specialty providers for children and youth with complex behavioral health conditions.

Screening and Assessment

Screening and assessment for behavioral health needs are indispensable components of behavioral health integration and availability in multiple settings and are essential for early identification and treatment planning. States can play a role in supporting and advancing these critical aspects of care, emphasizing the value of collaboration, education, and policy development.

The Screening, Brief Intervention, and Referral to Treatment (SBIRT) approach is an evidence-based and cost-effective way to identify and intervene with individuals with or at risk of substance use disorders in various community settings, including primary care and emergency room settings. At least 38 states offer Medicaid reimbursement for SBIRT. Originally SAMHSA grant-funded, Pennsylvania SBIRT (PA SBIRT) leveraged the Systems Transformation Framework to guide its implementation efforts. SBIRT Oregon was developed by the state to support education, training, and billing information to support providers. New Hampshire has broadened the reach of SBIRT, extending it to various sites and populations, including dentists, perinatal providers, and adolescents, and targeting alcohol and marijuana use in women.

To address the needs of transitional-aged youth (ages 16-25), the Connecticut Department of Children and Families and the Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services will join other stakeholders are part of the Connecticut Treatment Expansion and Enhancement (CT-TREE) initiative; a SAMHSA funded $2.7 million program that is implementing SBIRT and multidimensional family therapy for transitional aged youth in federally qualified health centers in the eastern part of the state.

Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) is a Medicaid benefit providing comprehensive and preventive medical, dental, vision, and behavioral health services for children and youth age 21 and younger in three buckets: screening, diagnostic, and treatment services. States may bolster behavioral health screening and assessments to expand early identification. In West Virginia, the HealthCheck children and youth benefit fulfills the state’s EPSDT requirements and supports the medical home approach to care. The state strengthens outreach and training for EPSDT by employing nine community-based regional program specialists who offer education and technical support to Medicaid providers to ensure compliance with the guidelines.

In Louisiana’s Coordinated System of Care (CSoC), youth are assessed using the Child and Adolescent Needs and Strengths (CANS) Comprehensive tool and the Independent Behavioral Health Assessment to determine clinical eligibility. These assessments occur within the first 30 days of referral and every 180 days thereafter. The wraparound agencies in CSoC oversee this process, ensuring timely and qualified assessment administration by licensed mental health professionals with CANS certification. Guidance is made available via the CSoC Standard Operating Procedure Manual.

Additional Resources

- CMS’s “SBIRT Services” booklet discusses eligible providers, covered services, documenting and billing SBIRT services, and dually eligible Medicare-Medicaid patients.

- CMS’s Birth to 5: Watch Me Thrive! efforts to ensure children receive developmental and behavioral screening.

First Episode Psychosis

Research on the effectiveness of early treatment of serious mental illnesses has led to state efforts to support the adoption of evidence-based practices and innovative models that emphasize low-dose antipsychotic medications, cognitive behavioral psychotherapy, family education/support, and vocational/educational recovery. Coordinated specialty care (CSC) has been well-documented in research and is operated in all 50 states. CSC employs a collaborative team of health care experts and specialists to collaborate with individuals and includes a strong emphasis on involving family members to the greatest extent possible.

New York City’s Supportive Transition and Recovery Team (NYC START) program is a free suite of services using the Critical Time Intervention model offered to young adults between ages 16 and 30 who are hospitalized for a first-episode psychosis. All New York City hospitals are required to report admissions meeting criteria for the START program to the health department within 24 hours. Referrals are made electronically through the NYCMED portal, after which NYC START staff will contact the hospital to provide information on how the program can be offered to eligible patients. Participants must opt into services, which are offered from the time of hospitalization through the first three months of discharge.

Additional Resources

- SAMHSA maintains an Early Serious Mental Illness Treatment Locator that includes CSC programs in the U.S. The SAMHSA evidence-based resource guide series titled First-Episode Psychosis and Co-Occurring Substance Use Disorders also provides valuable implementation information distilled from the research literature.

- The publication “Coordinated Specialty Care for First Episode Psychosis: Cost and Financing Strategies” provides an overview, including data on CSC program costs, financing methods, case studies on cost reimbursement, funding options, trends in costs, and an evaluation of Medicaid and private insurance coverage with identified barriers.

Crisis/Urgent Care: 988, Mobile Response, and Stabilization Services

To enhance community-based services and supports and reduce unnecessary use of acute care and institutional settings, states are prioritizing building a continuum of crisis services and supports based on the SAMHSA National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crisis Care, which include crisis call centers, mobile mental health teams, and facility-based care. States are ensuring that individuals in crisis receive the compassionate and timely support they need, ultimately contributing to improved outcomes and well-being.

State Actions to Build the Behavioral Health Crisis Continuum

A robust continuum of behavioral health crisis services is essential for timely interventions in cases of acute mental health and substance misuse needs. States play a vital role in building these systems, guided by national standards.

This resource provides insights into state innovations, offering delivery and payment strategies, funding approaches, and connections to community-based services, with ongoing updates to reflect the evolving landscape of state initiatives.

988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline

States have made significant strides in advancing the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline since it was signed into law in October 2020: More than 50 percent of states have enacted legislation designating 988 as the national emergency number for mental health and crisis services (see NASHP tracker “State Legislation to Fund and Implement the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline”). Furthermore, states have concentrated efforts on improving crisis call center infrastructure and bolstering the workforce to modernize behavioral health crisis care.

In Virginia, the state established a regional crisis call center approach with a $9.8 million investment, integrating public and private resources to provide comprehensive care and allowing private crisis providers to bill Medicaid or other insurance. States also continue to invest in specialized warmlines that compliment 988 and are tailored to the unique needs of specific populations. States that include Connecticut, Missouri, Oregon, Pennsylvania, Texas, Virginia, and Wyoming fund crisis specialists trained to understand the distinct culture, values, stressors, and experiences of agriculture workers. In New Mexico, the state’s Peer-to-Peer Warmline works in conjunction with the New Mexico Crisis and Access Line. Staff triages calls, offering an option to be connected to either a peer or a clinician, and connects people accordingly. Washington supported the development of the nation’s first crisis line dedicated to serving American Indian and Alaska Natives (AI/AN). When calling 988, AI/AN individuals will have an optional “off-ramp” to connect with the Native and Strong Lifeline, where calls are answered by Native crisis counselors who are Tribal members and descendants closely tied to their communities. The Native and Strong Lifeline counselors are fully trained in crisis intervention and support, with special emphasis on cultural and traditional practices related to healing.

CMS guidance also supports time-limited enhanced Medicaid federal match for administrative costs associated with operating state crisis access lines (50/50 match) and information technology system costs (90/10 match). This provides states with additional options to modernize behavioral health crisis care.

Mobile Crisis Response

States are taking various measures to expand the availability of mobile crisis response, including using Medicaid payments for qualifying community-based mobile crisis intervention services provided by the American Rescue Plan Act. This improves states’ capacity to deliver prompt and personalized assistance to individuals experiencing a crisis. CMS has approved Medicaid state plan amendments in Wisconsin, Indiana, Massachusetts, and Washington, DC.

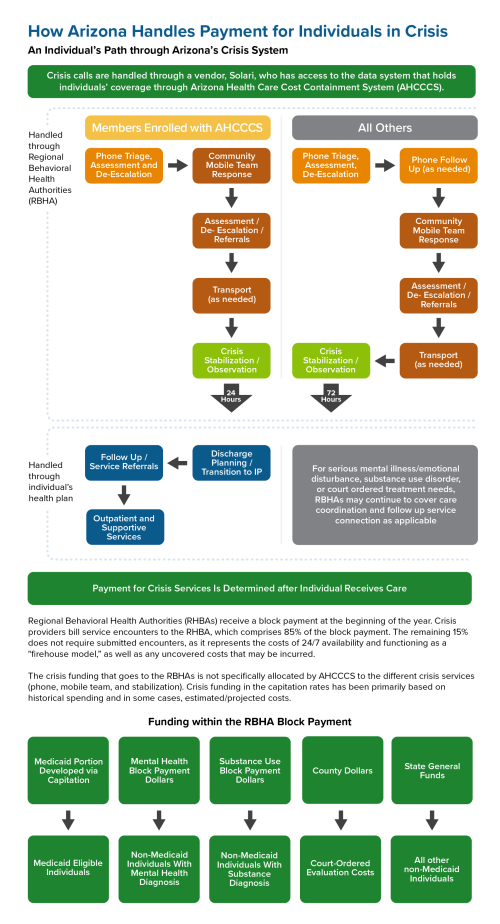

As noted in NASHP’s resource on the crisis continuum, Washington and Arizona created regionally based systems to cover more territory in a timely manner and provide financial support to mobile crisis response in less densely populated areas. Crisis response is available in both states regardless of insurance status and is run through managed care.

In response to a survey of county-level crisis administrators, Wisconsin addressed staffing and enhanced access needs by redesigning Medicaid billing codes to align with the Crisis Now framework. Changes include introducing a mobile crisis teaming response option, broadening the types of providers eligible for Medicaid reimbursement, and adding three new billing codes. These updates offer more detailed data for improvement and regional variation tracking.

States such as Indiana are leveraging the Mobile Integrated Healthcare-Community Paramedicine provision as part of its mobile crisis services strategy by bringing care into patients’ homes and facilitating connections with facility-based providers through telehealth. Through an advisory committee, allowable Medicaid funding, and leadership support, this approach is helping high-need individuals, including those with mental health and substance use disorder needs, be directed to appropriate non-emergency department sites for behavioral health services.

Crisis Response for Children, Youth, and Families

Mobile Response and Stabilization Services (MRSS) is a child and family crisis intervention model that provides crisis intervention services where a child and their family are experiencing the crisis — whether at home, school, or another community location — usually within one hour. MRSS operates within a 988 system and includes crisis intervention, up to eight weeks of stabilization services to support connection to community services to address the child’s needs, and continued intervention to maintain the child in their home.

Emergency Department Boarding

“Boarding,” in which admitted children and youth are kept in emergency department (ED) hallways or other temporary areas until inpatient beds become available, is a challenge that states and communities are grappling with as part of the children’s mental health crisis.

Interventions such as MRSS and other interventions noted here can help mitigate the problem by providing timely and specialized crisis intervention in the community, preventing unnecessary and prolonged ED stays for children and youth in crisis. In addition, states are exploring a range of solutions, including triage protocols to facilitate ED diversion, increased access to telepsychiatry, and more.

See “Practical Solutions to Boarding of Psychiatric Patients in the Emergency Department” for additional policy considerations.

In Oklahoma, the children’s mobile response and stabilization system includes rapid community-based mobile crisis intervention for children, youth, and young adults ages 25 and younger who are experiencing behavioral health or psychiatric emergencies. Services are accessed through two toll-free call lines available 24/7 supported by the state that provide a warm transfer to the local mobile response teams. Twelve contracted agencies provide mobile response services in all 77 counties Oklahoma counties. As with all MRSS models, the child, youth, or family define the crisis and receive a face-to-face or telehealth visit from 60 minutes to 72 hours after contact, unless declined by the family. Oklahoma’s mobile response team includes peer support specialists, care coordinators, and a licensed clinician. Additionally, up to eight weeks of stabilization services can be provided.

Connecticut’s mobile response, named Mobile Crisis Intervention Services (MCIS), provides face-to-face mental health crisis stabilization and follow-up services to all residents, regardless of payer, through a statewide network of 14 provider sites. MCIS is accessed by calling the state’s 211 or 988 lines. Mental health professionals respond in person within 45 minutes or less. In addition to funding mobile response services, Connecticut has also established a Mobile Crisis Intervention Services Performance Improvement Center (PIC) to support the collection and analysis of data, implement quality improvement activities, and support providers to enhance their clinical competencies and delivery of MCIS. Detailed reports are published quarterly, along with monthly dashboard reports.

New Jersey’s MRSS program — funded via the Medicaid Rehabilitation Option, state general revenue, and third-party liability coordination — has been highly effective in maintaining children in their home. Data demonstrate that 95–98 percent of children receiving MRSS remain in their current living situations, including children in foster care. Notably, New Jersey has expanded use of MRSS to include a proactive intervention for youth removed from their homes and placed into foster care. An MRSS worker is dispatched within 72 hours of the foster care placement, meeting with the child to address the trauma they are experiencing from the removal and meeting with the foster parents to provide strategies to support the youth.

Crisis Receiving and Stabilization Facilities

These facilitates offer a no-wrong-door approach to individuals of all ages, clinical conditions, and ability to pay, helping first responders and walk-in referrals avoid unnecessary acute or institutional care by providing referrals for medical treatment or specialized withdrawal management when necessary. A series of NASHP resources describe state efforts to improve access to crisis-receiving and stabilization facilities, including case studies on New York and Wisconsin.

Arizona’s “no wrong door” policy in crisis care includes 24/7 walk-in urgent care, 23-hour observation, and various arrival pathways, such as direct-field escorts, mobile crisis teams, walk-ins, or transfers from emergency rooms. The state’s model relies on a braided funding approach that prioritizes services and needs over payment considerations, seamlessly integrating resources from multiple sources.

States such as Virginia operate crisis stabilization units (CSU) to re-direct children from out-of-home services. It is important to note that CSU is different from the crisis stabilization services noted in the MRSS model above, though in many states CSUs are connected to the MRSS service. CSUs are 24/7 services in which the child stays at a facility to receive clinical care for a short period, often just a few days. These brief stays are achieved through emphasis on family-based interventions, care coordination, and engagement of clinical services to rapidly return the child to their home setting.

Oklahoma has four Children’s Recovery Center (CRC) urgent recovery clinics — and plans to open an additional nine in 2024–2025 — that are accessible 24/7 and aimed at the assessment and immediate stabilization of acute symptoms of mental illness, alcohol and other drug use, and emotional distress. The clinics use a family-style model of crisis intervention, diversion, and de-escalation in which most stays are less than 24 hours. If there is no way for the young person to remain safe with a plan in their community, services also include facilitation and coordination of transfer to crisis center, acute care hospital, or residential care for those assessed as needing a higher level of care.

In New York, Children’s Crisis Residence services encompass community-based crisis resources, such as crisis hotlines, mobile crisis intervention, and various components of children and family treatment and support services, along with comprehensive psychiatric emergency programs. For children in crisis requiring short-term higher-level care, the Children’s Crisis Residence offers an expanded benefit, providing the necessary support to ensure a more successful return home for both children and their families.

Peer-Operated Respite

Peer-operated crisis and respite programs provide individuals with alternatives to clinical settings, emphasizing recovery through a wide range of supports provided by individuals with lived experience. In New York, fully peer-run organizations like People USA, collaborate with the state to expand access to peer-run wraparound crisis services, including forensic mobile crisis teams, crisis stabilization units, and voluntary short-term crisis respite. This model has generated health care system savings and criminal justice system cost-avoidance.

In Georgia, Peer Support and Respite Centers, distinct from traditional mental health programs, provide 24/7 peer support in free respite rooms for up to seven nights every 30 days, with these services defined in the state’s behavioral health provider manual.

Massachusetts funds respite services that provide temporary short-term, community-based clinical and rehabilitative services that enable a person to live in the community as fully and independently as possible. Respite services are delivered in both site-based (24/7) locations and as a mobile service. The availability of community respite capacity increases emergency departments and psychiatric inpatient providers’ ability to discharge patients to the next treatment level, provides alternatives to hospitalization, and provides additional settings for clinical assessments.

Additional Resources

- The NASHP brief “The Rural Behavioral Health Crisis Continuum: Considerations and Emerging State Strategies” presents considerations and emerging state strategies for bolstering the rural behavioral health crisis care continuum at each level of care as defined by SAMHSA.

- The SAMHSA advisory “Peer Support Services in Crisis Care” outlines emerging state strategies to enhance the rural behavioral health crisis care continuum at each level defined by SAMHSA, providing insights for policymakers and practitioners in rural mental health services.

- The National Empowerment Center maintains a list of peer respite resources. State health officials may find this list useful in identifying and understanding available peer respite services, facilitating informed decision-making and strategic planning for mental health supports within the state.

- SAMHSA’s National Guidelines for Behavioral Health Crisis Care Best Practice Toolkit addresses program design, development, implementation, and ongoing quality improvement. It can aid mental health authorities, agency administrators, service providers, and local leaders in structuring crisis systems that effectively meet community needs.

- Mobile Response and Stabilization Services best practices for youth and families is available through the National Technical Assistance Network for Children’s Behavioral Health’s resource center.

In-Home and In-Community Based Services

Integrating mental health services within trusted community infrastructures extends clinic-based behavioral health care to communities in which people live, work, and thrive. With broad access, they reduce barriers to prevention and intervention.

States are actively modernizing their systems to better align with the core principles of community-based care, emphasizing the least restrictive environments and the highest potential for resilience and recovery. There are growing number of promising and evidence-based interventions policymakers and other invested parties can prioritize and customize to their needs, fostering a future in which in-home and community-based services are readily accessible and incorporated into daily life.

Certified Community Behavioral Health Centers (CCBHCs)

CCBHCs is a comprehensive model for community-based integrated, cost-effective, and high-quality mental health and substance use services in compliance with established federal criteria and reimbursement. States are employing various Medicaid options, such as the Section 223 CCBHC Medicaid Demonstration, State Plan Amendments (SPAs), and Medicaid waivers, to facilitate the establishment of CCBHCs. Efforts in more than 24 states involve significant work in building the necessary infrastructure, including rate methodology, application process, needs assessments, and implementation of a range of regulations and evidence-based practices.

In 2021, Kansas became the first state to pass legislation identifying the CCBHC model as a solution to the substance use and behavioral health crises. In 2022, Kansas received SPA approval from Medicaid for its CCBHC model and aims to implement CCBHCs in all 26 existing community mental health centers. All Kansas CCBHCs must use evidence-based practices of care including assertive community treatment (ACT), and a value-based payment model.

Missouri, the first state with an approved Health Home State Plan Amendment (in 2012) designed both primary care health homes and behavioral health care homes with notably improved health outcomes and reduced cost of care. Building on this model, the state was one of eight CCBHC demonstration states selected to pilot the new per-member per-month payment approach. A year-five impact report (2022) found the state had achieved reduced hospital cost and emergency department use, increased access to care and increased medication-assisted treatment uptake.

Fully Integrated Primary and Behavioral Health Care Settings

In a fully integrated setting, states that allow providers to be dually licensed in behavioral health (mental health and/or substance use) and primary care, and allow for same-day billing under Medicaid, enable providers to effectively use ACT services within a comprehensive model of care, as exemplified by Cherokee Health Systems in Tennessee.

In Florida, Medicaid Mental Health Targeted Case Management services provide case management to adults with a serious mental illness and children with a serious emotional disturbance to assist them in gaining access to needed medical, social, educational, and other services. This service is one of the minimum covered services for all Managed Medical Assistance plans serving Medicaid enrollees.

Massachusetts’s Integrated Care Management Program is an enhanced care management program offered to Primary Care Clinician Plan members with complex medical, mental health, and/or substance use disorders.

Assertive Community Treatment (ACT) is a team-based, outreach-focused intervention delivered through multi-disciplinary care teams offering more intensive services for people with serious mental illness (SMI) and/or co-occurring substance abuse. ACT has been shown to be effective in reducing homelessness and improving mental health and reducing unnecessary acute and institutional. Similarly, Critical Time Intervention as a care coordination model for people with SMI transitioning from institutional care to community settings is a best practice for successful transition to community and avoidance of poor outcomes such as homelessness. The vast majority of state Medicaid programs cover ACT, and providers have explored modified versions of this fidelity-based model to accommodate underserved populations while retaining key ingredients.

For example, the Montana Assertive Community Treatment program (MACT) is a service for individuals with “severe disabling mental illness” and who meet additional criteria and who require supports to maintain independence in their community. The service was approved as a State Plan Amendment in 2020 and received initial grant funding from the Montana Healthcare Foundation.

Intensive Outpatient Program (IOP) services play an increasing role in the modern behavioral health continuum of care, offering specialized services that address a range of mental health and addiction issues while allowing patients to continue to live at home. Furthermore, the integration of telehealth, hastened by the COVID-19 pandemic, has significantly enhanced the accessibility and flexibility of IOPs.

As of 2022, 34 states cover intensive outpatient treatment services in their Medicaid program. Starting in 2024, new Medicare Hospital Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) rules offer expanded payment options for IOPs across various settings, including hospital outpatient departments, community mental health centers, federally qualified health centers, opioid treatment programs, and rural health clinics. As states explore strategies to modernize the continuum of care, there is an opportunity to align their Medicaid program.

Substance Use Services and Supports

To address the evolving overdose crisis, states are developing strategies to increase access to evidence-based practices for substance use disorders (SUDs) in communities.

Access to Medication for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) is a critical component of addressing opioid overdoses driven by the presence of fentanyl in the illicit drug supply. Given the high potency of fentanyl relative to that of other opioids, demand is expected to increase for methadone — the most potent opioid replacement therapy. A shift to decriminalize SUDs and expand harm reduction have challenged the overregulated model of service delivery, which is framed as a barrier to care.

Missouri’s Medication First approach, modeled on the Housing First concept, provides a low barrier alternative to opioid use disorder treatment. Funded through State Opioid Response grants, this cost-effective application of an interim treatment model has led to quicker access to methadone and improved retention. Rates established for providers of the Medication First approach were developed to also cover ancillary services.

Similarly, the state and partnering providers have modernized the state’s Comprehensive Substance Treatment and Rehabilitation (CSTAR) service model. This initiative focuses on aligning rates with American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) levels and close gaps in payment through establishing daily rates to match increasing levels of service intensity. The state’s commitment to ongoing technical assistance and training underscores its importance in enhancing the quality and accessibility of SUD treatment services.

Contingency Management

The increasing presence of methamphetamine and other stimulants in overdoses, coupled with a relative dearth of treatment options for stimulant drug misuse, has revived focus on a long-standing intervention. Contingency management (CM) is an evidence-based treatment that reinforces individual positive behavior change consistent with meeting treatment goals, including abstinence and engagement in treatment, through the provision of motivational incentives. Multiple studies conducted over the past 30+ years demonstrate that CM is an effective intervention for SUDs, including for stimulants linked to methamphetamine, amphetamine, and cocaine.

Several states have created access to CM through State Opioid Response (SOR) grant funds. Kentucky used SOR funds to implement CM using a digital therapeutic app but received permission from SAMHSA to exceed incentive limitations to increase fidelity to the model.

Montana is using SOR funds to implement a pilot program for CM based on the TRUST clinical model. The state is exceeding incentive limitations using a braided funding approach, receiving approval from SAMHSA for this arrangement. In addition, Montana has received CMS approval for coverage of contingency management as a Medicaid service as part of the state’s HEART Section 1115 demonstration initiative.

In 2021, California’s 1115 Research and Demonstration Waiver request to include contingency management in the state’s Medicaid program was approved. While contingency management was tested in California using other sources of funding, it is the first state to receive federal approval of contingency management as a benefit in their Medicaid program.

Washington received approval for CM as a Medicaid covered benefit for eligible beneficiaries as part of its 2023 1115 renewal.

Recovery Services and Supports

Over the past 25 years, SAMHSA has made significant investments in the development, support, and implementation of recovery support services (RSS) throughout the U.S. From the Recovery Community Support Program, which began in 1998, to the current State Opioid Response grants, states have implemented these federal programs to spread access to RSS to individuals in need. More recently, states are more routinely engaging people with lived experience and peer support specialists in developing strategies and solutions and have increased investments in multiple forms of recovery support. A comprehensive review of state funding for RSS can be found in the Technical Assistance Collaborative’s 2023 report.

Additional Resources

- Transforming the Role of Opioid Treatment Programs by the Technical Assistance Collaborative includes recommendations for transforming substance use disorder (SUD) treatment services to encompass patient-centered access to methadone treatment alongside a comprehensive range of recovery support services. This includes recommendations for transforming substance use disorder (SUD) treatment services to encompass patient-centered access to methadone treatment alongside a comprehensive range of recovery support services.

- How States Are Leveraging Payment to Improve the Delivery of SUD Services — This toolkit examines Medicaid payment strategies used by four states to leverage provider payments to improve access, quality, and outcomes for substance use disorder treatment for Medicaid beneficiaries.

- Statutes, Regulations, and Guidelines, SAMHSA provides information of federal and state laws, regulations, clinical guidelines, and other resources related to the use of FDA-approved medications like methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone in medication-assisted treatment for opioid use disorders.

Social Drivers of Health: Evidence-Based Interventions

Addressing social drivers of health outcomes as a priority is a powerful and cost-effective intervention for people with serious mental illness and/or substance misuse that preserves dignity and supports community connectivity. In particular, supportive housing and supported employment enjoy a strong evidence-base and are linked to positive outcomes.

Permanent Supportive Housing, or a Housing First approach, is an evidence-based intervention that prioritizes providing permanent housing for people experiencing homelessness, combined with voluntary health, behavioral health, and other supportive services. It emphasizes individual choice and control, affordability, quality, and integrated community-based housing settings.

NASHP’s Health and Housing Resources provide lessons learned and practical strategies for state policymakers, including how states are leveraging Medicaid authorities to support housing-related services and foundational information for essential cross-sector approaches to health and housing strategies.

Louisiana’s permanent supportive housing program, established post-Hurricane Katrina, is a gold-standard cross-sector initiative that addresses housing and health care needs. It targets a diverse group, including individuals with disabilities and those at risk of homelessness or institutionalization, through partnerships with the Louisiana Department of Health (Medicaid provider and primary funding source) and the Louisiana Housing Corporation/Housing Authority (housing providers and subsidy administrators). The program combines various funding sources, such as Community Development Block Grants, state/federal vouchers, Medicaid, Ryan White HIV/AIDS funds, and Veterans Affairs resources. Evaluation outcomes from 2009 to 2018 include an 88 percent stable housing rate, a 68 percent reduction in homelessness, a 59 percent income increase, 26 percent fewer ED visits, 12 percent fewer hospitalizations, and a 23 percent rise in behavioral health services.

Several states are leveraging CMS equity framework and 2022 guidance to address health-related social needs through 1115 waivers to reform access to health related social needs for Medicaid enrollees (with housing at the leading edge). Others are using 1915(i), Home- and Community-Based Setting (HCBS) rules or working through Medicaid managed care partnerships such as in California’s CalAIM initiative.

Recovery Housing is a recovery support service designed by people in recovery specifically for those starting and sustaining recovery from substance use issues. For many individuals, recovery housing is a critical component of the continuum of care for substance use disorders. A “recovery house” is a broad term describing a sober, safe, and healthy living environment that promotes recovery from alcohol substance misuse and associated issues. A recovery house provides a safe and healthy living environment that fosters improvement of physical, mental, spiritual, and social well-being. Many states such as Indiana and Pennsylvania have enacted legislation that makes the receipt of state and local funds dependent on meeting certain quality standards. Pennsylvania includes that licensed recovery houses that receive funds or referrals from a federal, state, or other county agency may not discriminate against individuals who receive MOUD or any other form of treatment.

The Missouri Department of Mental Health Division of Alcohol and Drug Abuse determined grant eligibility by evaluating survey responses that gauged how much support recovery house operators provide to residents on medication-assisted treatment (MAT). Operators whose responses indicate that they are not supportive of individuals on MAT do not qualify for funding. Many states, such as Rhode Island and Kentucky, serve as the certification and oversight body for recovery housing, working to certify houses to meet the national standards for different levels of recovery residences. Oxford Houses are an example of a Level I recovery residence, California Sober Living is an example of a Level II recovery residence, and therapeutic communities that combine social model recovery and clinical services are examples of Level IVs.

Michigan used a multifaceted approach to double the available beds by encompassing state-specific training, onboarding the use of a recovery capital assessment instrument, and allocating opioid litigation settlement funds to support the acquisition or long-term lease of recovery residences in underserved areas.

States are also using the National Opioid Settlement Fund to invest in recovery housing. Indiana is issuing grants for qualified community organizations to purchase, build, renovate, or otherwise sustainably buy a suitable structure for a recovery residence certified by the state’s Division of Mental Health and Addiction. Wisconsin is using $2 million of opioid settlement to fund the Recovery Voucher grant program.

Supported Employment helps people with serious mental illness work in regular, competitive jobs. Employment is a major driver of improved quality of life and health outcomes, and most people with serious mental illness want to work. The Individual Placement and Support (IPS) model of supported employment is an evidence-based initiative that helps individuals find jobs with competitive pay in integrated community-based settings and provides supports to ensure success in the job. Recent data from across the country show the growth of successful competitive employment across 343 agencies that provide IPS services.

Washington State, under its Medicaid Section 1115 demonstration waiver, received approval for the Foundational Community Support program, which includes supportive housing and supported employment for eligible Medicaid members. A preliminary evaluation found that supported employment was associated with significant improvements in employment, earnings, and hours worked. It prioritizes Medicaid members with significant barriers to finding stable housing and employment and who meet specific medical risk factors such as chronic homelessness, complex behavioral health and co-occurring substance use needs, and disability or long-term care needs. Services for eligible members include employment assessment and planning, job development, job search, career advancement exploration, negotiation with employers, job coaching, benefits education, and asset development.

To address the overwhelming impact of substance misuse in the state, New Hampshire became the first state to create the Recovery Friendly Workplace (RFW) initiative. The mission of the RFW initiative is to promote individual wellness by creating work environments that further mental and physical well-being of employees, proactively preventing substance misuse, and supporting recovery from substance use disorders in the workplace and community. Employers receive a special designation from the state and are provided resources such as toolkits, training, connection to resources, and support for supervisors and employees. The RFW is funded by the U.S. Department of Labor Dislocated Worker Grant, the State Workforce Innovation Board Governor’s Discretionary Funds, and other state funds. The state allocated a one-time $1 million appropriation to the Community Development Finance Authority to administer grant funds to nonprofit organizations to deliver programming through the RFW initiative.

School-Based Behavioral Health Approaches

States are taking into account numerous considerations and adopting a wide range of strategies to bolster behavioral health services for children in school. In 2014, CMS advised states of their opportunity to cover all health services delivered to Medicaid-covered students. Half of the states have expanded Medicaid reimbursement in schools, with 17 receiving SPA approval. Pennsylvania and Iowa are implementing other approaches, including hiring dedicated behavioral health professionals in schools for service provision, expanding access to school-based health centers, and developing streamlined referral points to seamlessly connect students with necessary behavioral health services. These multifaceted approaches demonstrate the commitment of states to ensure that students have access to the mental health care they need.

Opportunities to reach more youth and offer services where most youth spend the majority of their time have led to integrative collaborative models in school settings. The Montefiore School Health Program in New York provides an interdisciplinary approach to health care, addressing both physical and mental health, as well as community-based strategies to engage families in wellness. As noted in the NASHP blog post “States Take Action to Address Children’s Mental Health in Schools,” more than 38 states have enacted nearly 100 laws focused on supporting schools in their role as one of the primary access points for pediatric behavioral health care

- California’s Children and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative (CYBHI) is part of the Governor’s Master Plan for Kids’ Mental Health and brings together collaborators to address a wide range of strategies.

- Wisconsin’s vision for comprehensive school mental health is encapsulated in the Wisconsin School Mental Health Framework. The framework outlines six key components of a Comprehensive School Mental Health System (CSMHS) and offers guidance for implementation, emphasizing a trauma-sensitive approach to ensure holistic student well-being and academic success.

- Handle with Care, an innovative service initiated in West Virginia, is designed to support children who have experienced traumatic events. Law enforcement agencies, schools, and behavioral health providers collaborate to ensure that students who encounter trauma receive the necessary school- and community-based supports, promoting their mental well-being and academic success.

Additional Resources

- “School Medicaid Expansion: How (and How Many) States Have Taken Action to Increase School Health Access and Funding” provides a summary of the actions each state took, along with related state documents and other resources that may be helpful to states working to increase access to and funding for physical, behavioral, and mental school-based health services.

- “Advancing Comprehensive School Mental Health Systems: Guidance From the Field” provides insights and guidance to assist local communities and states in developing high-quality comprehensive school mental health systems to support students.

- The NASHP blog post “States Take Action to Address Children’s Mental Health in Schools” highlights trends in state laws enacted to support children’s mental health through schools.

- “Best Practices in School Mental Health for At-Risk Youth and Paths to Treatment” is a PowerPoint presentation by Sharon A. Hoover of the University of Maryland School of Medicine National Center for School Mental Health. It addresses strategies to incorporate mental health as part of state and local school safety planning and budgeting.

- The NASHP report “How State Medicaid Programs Serve Children and Youth in Foster Care” examines state Medicaid delivery systems for children and youth in foster care (CYFC), focusing on the structure, selection of service delivery models, utilization of specialized Medicaid managed care programs, and provision of services, including enhanced services availability for CYFC.

- “Fostering School-Based Behavioral Health Services: Innovative and Promising Models, Policies, and Practices From Across the Nation” includes state-specific examples that can inform state planning efforts.

- “State Medicaid & Education Standards for School Health Personnel: A 50-State Review of School Reimbursement Challenges” provides recommendations and highlights promising practices and recommendations for states.

Wraparound

Wraparound is an intensive holistic approach to care coordination designed for youth with complex needs, including children, youth, families, and communities, to allow them to remain safely in their community. Wraparound models vary widely, but common services include case management, counseling, crisis care, special education services, caregiver support, psychiatric consultation, health services, legal services, residential treatment, and respite care.

The Wraparound program in Nevada (Wraparound In Nevada for Children and Families (WIN)) is a statewide community-based implementation approach providing a tiered care coordination approach to serving children and youth with severe emotional disturbances and complex behavioral and mental health needs. The model’s tiers are split between high-fidelity wraparound services for children and youth with more severe needs and FOCUS Program services for children, youth, and families just entering the child service system.

Child Specialty Managed Care Approaches

State Medicaid agencies are increasingly providing services to children and youth through managed care approaches. Several states have designed and implemented child and youth-specific Medicaid managed care approaches, such as Ohio’s Resilience through Integrated Systems and Excellence, a specialized managed care system for children and youth with complex behavioral health needs. Other states have developed cross-system managed care approaches that include Medicaid, child welfare, and/or juvenile justice. These states include New Jersey, West Virginia, and Washington. NASHP resources on state innovations include the report “How State Medicaid Programs Serve Children and Youth in Foster Care,” two maps, and an accompanying chart that highlight key characteristics of states’ Medicaid managed care programs that serve children and youth with special health care needs. Efforts such as these support states in developing targeted solutions to address their most compelling child and family policy issues, including reducing out-of-home treatment.

Individuals who have received diagnoses for both a mental health disorder and an intellectual or developmental disability frequently encounter challenges to accessing high-quality services and supports, in part due to poor alignment of systems, financing, and services. There is a pressing demand for comprehensive, collaborative, and interdisciplinary integrated approaches, encompassing various disciplines, to effectively provide holistic support for these individuals.

As part of New Jersey’s fiscal year 2024 efforts, the state will invest $100 million for home- and community-based services and dedicate funding for direct support professionals (DSPs) to obtain a national intellectual/developmental disabilities and mental illness (IDD/MI) dual diagnosis specialist certification to enhance training for DSPs supporting individuals with IDD/MI. The initiative will complement new state funding to launch a START program that will establish new community crisis prevention and intervention services. It follows a range of efforts over the past five years, including funding for additional community-based emergency beds and the creation of community-based and acute behavioral stabilization programs that expand the array of services available for individuals with developmental disabilities and complex behavioral and mental health needs. States such as Pennsylvania are adding competency-based certifications requirement into their Section 1915(c) Home- and Community-Based Services Medicaid waiver program rules that at least one staff person must have required certifications or degrees to provide enhanced levels of service to help ensure that these enhanced services are performed by qualified individuals. The range of long-term supports and services used by individuals with intellectual and developmental disabilities can vary significantly.

Out-of-Home Services

Out-of-home interventions vary based on acuity and chronicity of illness and challenges with functioning in routine daily living. Often “out-of-home” options are residential or institutional settings such as hospitals, jails/juvenile detention, nursing homes, and rehabilitative and residential settings of care. While they should be an option of last resort, when out-of-home options are necessary, they should be person-centered, trauma-informed, and least restrictive as possible with a prevention, resiliency, and recovery philosophy. Opportunities for continuous assessment and a transition to less-restrictive settings are paramount. This approach aligns with SAMHSA’s commitment to recovery, resilience, and dignity.

Out-of-Home Services and Interventions for Children and Youth

Specialized programs and facilities have been designed to address the unique needs of children and youth facing mental health and substance abuse challenges. These services can encompass children’s mental health residential services, youth substance abuse residential services, and therapeutic foster care. For more detailed information on these services, their availability, and the best practices surrounding children’s mental health and substance abuse care, please refer to specialized resources and agencies that focus on pediatric and adolescent mental health, child welfare, and substance abuse prevention and treatment. These resources can offer in-depth insights and guidance on how to best support the specific needs of children and youth facing these challenges.

When states strategize service coordination across various agencies and payers, they can harness the power of comprehensive frameworks, such as the following two frameworks, to bolster their initiatives:

- SAMHSA’s “National Guidelines for Child and Youth Behavioral Health Crisis Care” offers a framework that states and localities can use when establishing or expanding crisis safety nets for youth and families, promoting standardized and effective crisis response.

- The Building Bridges Initiative offers a framework for child welfare providers, enhancing outcomes for children, youth, and families in both residential and community-based settings.

In New York, a child-specific crisis residence program developed as part of the Children’s Medicaid Transformation offers enhanced resources for children in psychiatric crisis within the Medicaid system. Accessible through both Medicaid managed care and fee-for-service, this expansion facilitates easier access during a child’s psychiatric crisis. The programs detailed in the state’s manual are part of the crisis stabilization/residential supports component within the crisis intervention services authorized under the Medicaid State Plan.

Olmstead

Over 20 years ago the Olmstead v. L.C decision established that unjustified institutionalization of individuals with disabilities by a public entity is a form of discrimination under the Americans with Disabilities Act — a pivotal 1999 United States Supreme Court ruling. States continue to respond to (or build upon the successes from) Department of Justice settlements that require the shift to more community-based care. Implications for the Medicaid program are detailed in this MACPAC brief. Various Medicaid approaches are employed by states to implement and support these shifts. In Georgia, the Olmstead settlement and the strategic goals continue to inform state planning efforts to avoid institutional placement when appropriate and to integrate eligible individuals into the community at a reasonable pace. The state website highlights early successes. Spurred by this work, Georgia was the first state to receive CMS approval to reimburse peer support as a statewide mental health rehabilitation option service. Delaware resolved its Olmstead settlement in late 2016 with significant reforms in place, including a 92 percent increase in Medicaid-eligible people receiving community-based services. In addition, mobile crisis and walk-in centers are diverting 70-90 percent of individuals from more restrictive settings, such as hospitals and jails. Ongoing opportunities exist to use an Olmstead framework to reduce the significantly disproportionate number of people with mental illness in the criminal justice system. Through Nevada’s Department of Health and Human Services Aging and Disability Services Division, the state undertook a comprehensive planning process to create a new Olmstead plan for the division. Planning efforts included a steering committee, a detailed multi-year timeline, research, and public engagement, all culminating in the release of a new plan in November 2023. The plan includes established goals and objectives and will be used as a management tool to track progress. Arizona elected to develop an Olmstead plan, and, since 2001, has worked across its health and human services and economic security departments to continue updating and implementing the plan. The most recent plan (2022) incorporates Medicaid innovations such as the Housing and Health Opportunities demonstration waiver, new standards to support integration into community of choice under the Home and Community Based Settings Rules, and the Behavioral Health Continuum of Care.

States are increasing accountability and safety measures to improve the quality of out-of-home services (including incorporation of trauma-informed care). For example, in Montana, Senate Bill 4 requires that each mental health facility publish policies and procedures that define the facility’s guidelines for detecting, reporting, investigating, determining the validity, and resolving allegations of abuse or neglect.

Additional Resources

- “Olmstead at 20: Using the Vision of Olmstead to Decriminalize Mental Illness” examines new policy developments promote community integration.

- SAMHSA Olmstead v. L.C. Resources offers guidance for planning and implementing community integration initiatives. This includes a 2023 report that examines the most recent litigation involving community integration of people with mental illness.

- A 2023 U.S. Department of Justice blog post notes state efforts.

Inpatient Substance Use Treatment Services

States play a critical role in hospital- and community-based inpatient substance use disorder (SUD) services by overseeing and regulating facilities to ensure they meet established standards for safety, quality of care, adherence to evidence-based practices, and transition to community-based outpatient treatment and recovery support options.

This approach ensures a comprehensive and sustained recovery journey, regardless of whether someone starts in a hospital or community setting. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Office of the Assistant Secretary for Planning and Evaluation compendium on “State Residential Treatment for Behavioral Health Conditions” provides comprehensive insights into how each state regulates and funds services in residential mental and substance use disorder treatment settings, highlighting the diversity in their approaches. States are leveraging licensure and Medicaid policies to enhance the regulation and oversight of residential SUD treatment.

States such as Minnesota continue to codify required alignment with ASAM criteria. Recognizing the increased overdose risk associated with inpatient detoxification, Connecticut was an early adopter of offering medication induction to treat opioid use disorder as an alternative to abstinence-based medical withdrawal in inpatient centers. The state authorized both freestanding detoxification facilities and inpatient general/acute hospitals to bill standard detoxification codes, whether the goal was withdrawal to abstinence or withdrawal management to medication induction, eliminating the barrier of inadequate compensation for care. While not a state initiative, integrated provider models offer insights that can inform state efforts. SSTAR, a Federally Quality Health Center (FQHC) and CCBHC in Fall River, Massachusetts, collocates inpatient detoxification and crisis stabilization services with outpatient SUD and physical and mental health services. The program provides the full continuum of care for SUD including MOUD, all on the same campus, facilitating seamless transitions from detox to MOUD.

In the past five years, the Medicaid landscape has changed to reflect a growing need for temporary inpatient care for people with more intense service needs. 2017 CMS guidance provided an opportunity for states (through 1115 demonstration waivers) to waive the institutions for mental diseases (IMD) exclusion and receive federal financial participation in Medicaid payments for IMD services — defined as a hospital, nursing facility, or other institution of more than 16 beds with a primary focus on care of people with mental illness. Currently, 37 states have obtained or are in the process of seeking an 1115 waiver of the IMD payment exclusion for SUD treatment. Requirements include states indicating how inpatient and residential care will fit into a robust continuum of care. Subsequently, the Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment for Patients and Communities (SUPPORT) Act introduced a new state plan option that has since expired in September 2023.

Settings of Incarceration

A significantly disproportionate number of incarcerated individuals are dealing with a mental illness and/or substance use disorder. Approximately 40 percent of the jail and prison population have a mental illness, and approximately 60 percent have a substance use disorder. For youth, the situation is even starker: Over half of youth in correctional settings have a substance use disorder and 70 percent have a mental illness. For years, states have used the Sequential Intercept Model to divert people at different points of entry into the criminal justice system to more appropriate community-based services and supports. Providing access to health care and wrap-around support services during the reentry process is pivotal to improving outcomes, reducing recidivism, and reducing costs.

The Kentucky Judicial Commission on Mental Health was established in August 2022 by Supreme Court Administrative Order 2022-42. The commission is charged with exploring, recommending, and implementing transformational changes to improve systemwide responses to justice-involved people with mental health challenges, substance use issues, and/or intellectual and developmental disabilities. More than 1,000 people attended the Commission’s Mental Health Summit in Louisville to inform this effort. Through the commission, the state undertook a comprehensive approach to identify resources and service gaps within the criminal justice system. It conducted a Statewide Sequential Intercept Model Mapping workshop, resulting in key recommendations. They included positioning courts and conveners and leaders; engaging multi-sector partners to develop training programs; enhancing data-driven decisions, including a “Behavioral Health Data Elements Guide for State Courts”; creating a statewide public health model for a behavioral health continuum of care; and meaningfully incorporating people with lived experience in implementation efforts.

In the past year, the federal policy landscape shifted to catalyze new opportunities for cross-sector strategies to reduce criminalization of people with mental illness and substance use disorder. For the first time since 1965, Medicaid is being authorized to cover some health services pre-release from incarceration. The Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2023 included new provisions for justice-involved youth, including a requirement for pre-release screening and diagnostic services in accordance with the EPSDT requirements and the option to provide Medicaid/CHIP coverage to youth in public institutions who are pending disposition of charges with federal financial participation (which had previously been prohibited under the “inmate exclusion”). In addition, CMS provided guidance encouraging states to apply for new Medicaid Reentry 1115 demonstration waivers. Waivers in California and Washington have been approved, and more waivers are pending.

Forensic Hospital Settings

Specialized forensic hospital units within a psychiatric hospital or mental health facility are specifically designed to treat individuals with mental health issues who may have been found not guilty by reason of insanity, deemed incompetent to stand trial, or require mental health treatment while incarcerated. Modern state forensic systems should enhance public safety, promote recovery, reduce recidivism, and foster a compassionate approach to justice. States are struggling with several forensic challenges, including wait times for defendants referred for behavioral health services related to competency to stand trial (CST). A Behavioral Sciences & the Law research article noted wait times for CST evaluations range from 55 days to 11 months in some states.

Restoring Individuals Safely and Effectively (RISE): Colorado’s Jail-Based Competency Restoration Program is a promising practice that allows some defendants, who may not require hospital level care, to receive competency restoration services while living in the community, instead of an institutional setting such as a jail or hospital.

In Utah, the Utah Substance Use and Mental Health Advisory Council is being tasked with studying and informing the state on potential regulations and laws for individuals in the custody of the Department of Corrections. Individuals with lived experience are being added to advisory councils in Connecticut. In Washington, legislation is attempting to improve timely competency evaluations and restoration services to people with behavioral health disorders. This includes the proposal of a state contract for 60 beds to address the needs of misdemeanor and lower-level felony cases currently on the forensic admission wait list.

Additional Resources

- The National Center for State Courts “Leading Change Guide for State Courts” and “Reports and Recommendations” provides recommendations to assist state courts in their efforts to more effectively respond to the needs of court-involved individuals with severe mental illness.

- The “Behavioral Health Data Elements Guide” offers a structure for state courts to gather and analyze data, aiming to enhance their ability to address the requirements of court users with behavioral health conditions.

- The Health and Reentry Project acts as a resource for information on reentry issues and a linkage for ongoing cross-sector engagement.

Nursing Homes

Of the nearly 1 million people in nursing homes, over 30 percent have a psychiatric diagnosis of anxiety or depression. Nursing homes, along with jails and prisons, are a primary setting of care and support for people with serious mental illness in the absence of community-based alternatives. Some estimates show that Medicaid enrollees with schizophrenia are four times more likely than those without to spend time in nursing homes, which are not set up to serve the complexities of this population. The National Academies of Medicine report on improving nursing home quality recommends a number of improvements to address behavioral health and social drivers of health needs, including interdisciplinary care planning, behavioral health strategies included in emergency response, and workforce and quality measures.

States are pursuing several approaches to support community-based alternatives. Texas initiated a Money Follows the Person (MFP) Behavioral Health project in 2008, with the aim to help adults with severe mental illness in transitioning out of or avoiding placement in nursing homes. An evaluation of this initiative revealed favorable results and high participant satisfaction. These transitions are facilitated through grant funding, bolstered by Federal Medical Assistance Percentage enhancements, and carried out in coordination with the Texas Department of Housing and Community Affairs.