You are viewing one section of the Public Health Modernization Toolkit. Please check out the other two sections:

Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic pushed public health systems across the United States to their limits, with historic underinvestment, a depleted workforce, and legacy data systems hindering the ability of policy and health care leaders to understand and respond to the spread of the virus. However, while the pandemic revealed gaps in the U.S. public health system, the COVID-19 pandemic also served as an inflection point and policy laboratory for how public health can more meaningfully engage and partner with health care system partners and impacted communities in crafting effective responses to shared health challenges.

Sustaining partnerships catalyzed by the pandemic and applying lessons learned to other health challenges will require parallel efforts: First, promoting sustained investment in public health system capacity, as envisioned in many of the published frameworks and recommendations that have guided the broader vision of a strengthened and modernized public health system.[1] Second, fostering joint efforts among health care system partners and public health to drive action on common priorities. When aligned with state Medicaid and other health and human services efforts, state leaders can play a leadership role in advancing whole-person care and community investment approaches that more effectively and efficiently leverage the resources of each sector.

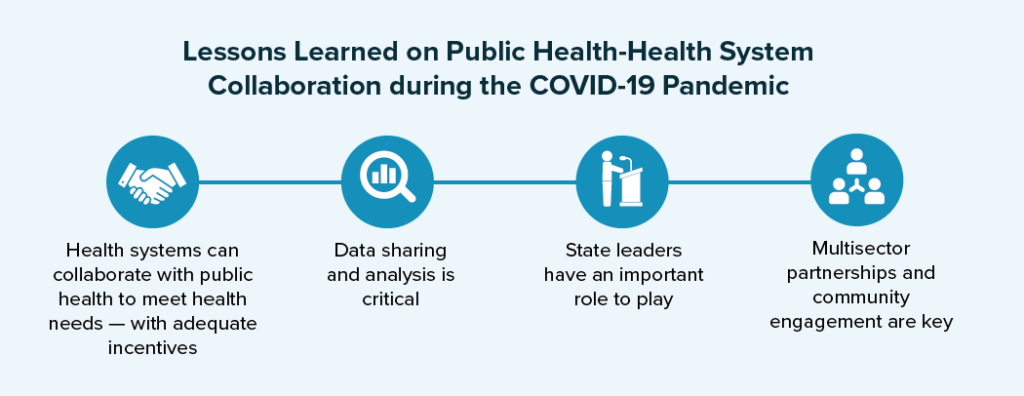

As policymakers look beyond the immediate public health emergency, strengthening collaboration between public health and health care system partners is critical to a modernized public health system that is robust, interconnected, and capable of promoting the health of all communities. Although efforts to modernize public health systems predate the COVID-19 pandemic, lessons learned from successful community and cross-sector partnerships in pandemic response (see Lessons Learned on Public Health-Health System Collaboration during the COVID-19 Pandemic) underscore the need to further integrate these systems toward common goals. Public health can be a leader in advancing these collaborative efforts by bringing together health care delivery systems, human and social service partners, and community leaders to drive informed collective action and community investment approaches toward improved population health.

A Framework for Advancing Collaboration between Public Health and the Health Care System

While there is no “one size fits all” approach to fostering collaboration among public health and broader health care system partners, state leaders can look to a number of principles and strategies that can bolster collaboration across a variety of settings. The National Academy for State Health Policy’s (NASHP) Public Health Modernization Toolkit builds on efforts to strengthen public health by providing state policymakers with a menu of strategies and innovative practices for aligning public health and broader health care system efforts around key public health priorities. It starts concretely with strategies for high burden, high-cost health conditions that are priorities for both sectors.

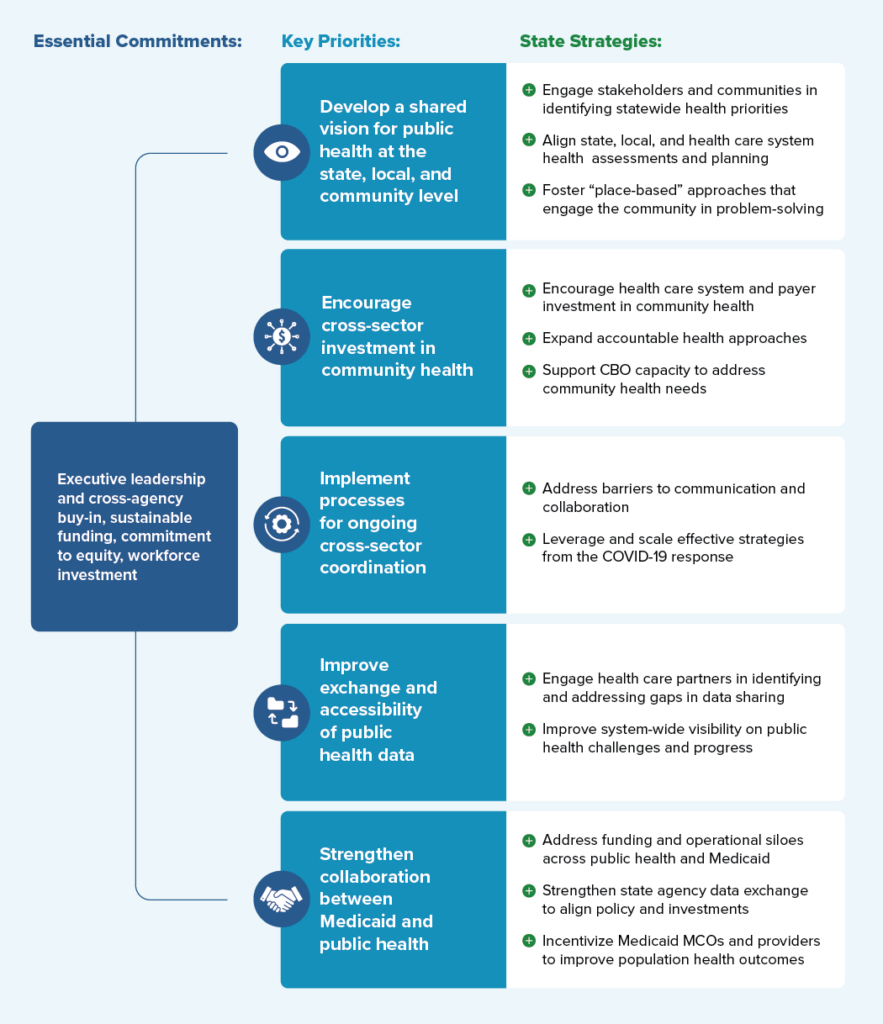

Drawing on interviews with cross-agency state leaders and public health experts, local leaders, and scientific and grey literature, this toolkit provides a framework for understanding essential commitments, key priorities, and policy strategies for fostering collaboration among public, private, and community partners to improve population health outcomes. Figure 1 displays a consolidated overview of the “Framework for Public Health-Health Care System Collaboration.” Specific examples taken from a variety of states will be examined in greater detail throughout the toolkit.

Figure 1: Public Health-Health Care System Collaboration Framework

Why Collaboration between Public Health and the Health Care System Matters

Throughout the history of public health in the U.S., advances in scientific knowledge related to infection control, nutrition, and sanitation have fueled improvements in overall population health. As state and local governments took increasing responsibility for public health in the 20th century, public health achievements such as vaccinations, workplace protections, and flouridation of drinking water have contributed to dramatic increases in life expectancy. In contrast to population-based interventions and upstream prevention that have traditionally been the realm of public health, the U.S. health care system — a fragmented system of public and private insurers and providers — that emerged in the latter half of the 20th century has primarily focused on the provision of individual clinical services.

Several shifts have prompted a rethinking of how public health and health care systems engage one another to promote overall health. First, although some state and local public health agencies continue to serve a “safety net” role in providing clinical services to areas that lack provider capacity, there has been a trend away from public health providing direct health care services and toward reliance on local health care infrastructure to fulfill that need. Second, despite the continued threat of infectious diseases, non-communicable diseases such as heart disease, cancer, and injury (e.g., drug overdoses, vehicle accidents) have overtaken infectious diseases as the leading causes of morbidity and mortality in the U.S. Third, the growing recognition of the role of social determinants of health in driving health outcomes and health care costs has led to increased health care delivery system investment in upstream prevention activities and community investment traditionally in the realm of public health. Through a new health equity framework from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) and newly approved Medicaid authorities to address health-related social needs, states are partnering with health care systems to advance both individual and population-based health outcomes and strategically invest in community. These shifts present a significant opportunity for cross-sector alignment and optimization.

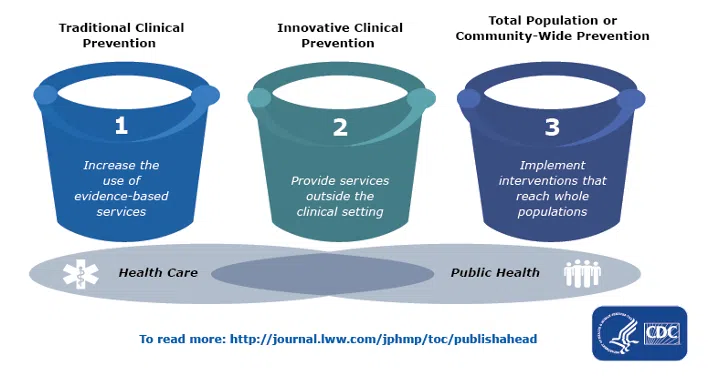

Finding common priorities between public health and health care systems to prevent and mitigate the burden of high-priority, modifiable, and costly conditions (e.g., diabetes and heart disease) is at the heart of the role of governmental public health envisioned in Public Health 3.0 and John Auerbach’s “Three Buckets of Prevention” (see Figure 2) and is exemplified in efforts such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC’s) 6|18 Initiative.

Figure 2: Three Buckets of Prevention

In particular, public health and health care system partners have shared interests in working together within the innovative clinical prevention domain (Bucket 2) to better align health care and public health, create cost-efficiencies, and bolster the unique contributions from each sector.

While public health and health care systems may have real and theoretical incentives for partnering on community-focused interventions, implementing these efforts in practice can be challenging across the state health landscape. Each state has a complex ecosystem of agencies and partners that play a direct role in individual and community health, including state-level health and human services agencies, Medicaid programs (and their managed care partners), behavioral health agencies, commerce and economic security, workforce departments, housing agencies, departments of insurance, state employee and retiree health plans, commercial insurers, local health departments, commercial and nonprofit health care systems, health care providers, community health centers and other safety net providers, tribal health organizations, area health education centers in rural areas, faith-based partners, and community-based organizations (CBOs). Additionally, public health and health care systems have differing missions, incentives, and cultures that may complicate collaboration. The fragmentation and variability of public health structures across states (where public health governance structures can be centralized at the state level, decentralized, or mixed), as well as variation in the level of clinical work and service delivery performed by public health agencies at the local level, can make implementing uniform approaches to addressing community challenges difficult. Taken together, the unique public health and health care infrastructure in each state may offer both strengths and weaknesses in the ability to respond to health challenges. State leaders will need to build on existing systems, cultivate trust, and engage partners in developing solutions to fit each state’s unique infrastructure and needs.

Endnotes

[1] High-level frameworks and recommendations include Public Health 3.0, the Commonwealth Fund Commission on a National Public Health System’s “Meeting America’s Public Health Challenge: Recommendations for Building a National Public Health System that Addresses Ongoing and Future Health Crises, Advances Equity, and Earns Trust;” the Bipartisan Policy Center’s “Public Health Forward: Modernizing the U.S. Public Health System;” the Public Health National Center for Innovation’s Foundational Public Health Services; the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Essential Public Health Services.