Section 3a of the RAISE Act State Policy Roadmap for Family Caregivers

This section of the RAISE Act State Policy Roadmap focuses on state opportunities to support services for families caring for older adults and adults with disabilities. Family caregivers are the major providers of long-term services and supports(LTSS), with an estimated economic value of unpaid contributions totaling approximately $470 billion in 2017.

The COVID-19 pandemic heightened reliance on family caregivers. Although states can promote family caregiver services through licensure, regulation, and outreach, the most powerful policy lever that states have to increase access is funding key services and supports.

How States Assist Family Caregivers

Under the Older Americans Act, states fund family caregivers services and supports, which include:

- Information about available services

- Assistance in gaining access to the services

- Individual counseling, support groups, and caregiver training to assist caregivers in making decisions and solving problems

- Respite care to temporarily relieve caregivers

- Supplemental services, on a limited basis, to complement the care provided by family caregivers

These services can reduce caregiver depression and stress so caregivers are able to provide care longer, thereby avoiding or delaying the need for costly institutional care.

Medicaid is the largest source of public funding that can be leveraged to support family caregivers. States can support family caregivers through a range of Medicaid authorities and state plan amendments.

States widely use 1915(c) waivers to provide a range of home and community-based services (HCBS) to targeted populations in Medicaid. Those services can include caregiver education, counseling, and training as well as adult day and respite care. States may also incorporate family caregivers into self-direction options within Medicaid waivers, where states can allow care recipients to select, manage, and pay their service providers, which can include family caregivers.

The 1115 demonstration waiver authority allows states to provide greater access to services for family caregivers. Some states use this authority for Medicaid managed LTSS programs to give managed care organizations greater flexibility with program benefits. Medicaid services, however, are targeted to care recipients, and the provision of family caregiver services must be in aid of the care recipient.

States can utilize other resources for family caregivers such as federal funding, including the National Family Caregiver Support Program and state general revenue dollars. Given limited resources, states often blend and braid funds from multiple funding sources for family caregiver services.

The pandemic has highlighted the need to support family caregivers, and recent federal funding is supporting state momentum to increase family caregiver services. States have a strong rationale to do so:

- Investment in family caregiver supports can lower overall state spending on LTSS. Washington state’s 1115 waiver program, the Medicaid Transformation Project, has demonstrated both cost-savings and improved outcomes from its two caregiver support programs (more details are below).

- Family caregiver supports can be a component of states Medicaid rebalancing strategies, helping loved ones remain in home and-community based settings — while potentially reducing costly hospital and nursing home services.

- Family caregivers can help ease the current LTSS workforce crisis. States are actively looking for ways to address extreme direct care workforce shortages and invest in family caregivers, as evidenced by the uptake of Medicaid self-direction programs through Appendix K waivers authorized during the public health emergency, and a range of state investments in family caregiving using the enhanced HCBS federal match funded through the American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA).

State Challenges

While supporting family caregivers can help lower costs and improve care, states face barriers in providing a range of supports for families:

- Inadequacy of dedicated resources: Funding for family caregiver supports is very limited, and few resources are specifically designated for family caregivers. Medicaid, the largest public payer for LTSS, focuses on beneficiaries — who are primarily low-income families and people with disabilities —— rather than family caregivers. The Older Americans Act funds services for family caregivers, although significantly less than Medicaid. The National Family Caregiver Support Program provides grants to states through Title IIIE of the Older Americans Act. States receive funding to help family caregivers provide care at home based on their share of the population age 70 and over. The Act provided dedicated funding for family caregiver supports totaling $189 million in FY 2021, with an additional $145 million in supplemental pandemic funding. Older Americans Act programs leverage around three dollars of non-federal money for every one dollar of federal funding in a state, which far exceeds the program’s matching requirements.

- Lack of data: The involvement of a family caregiver is not uniformly captured in medical records or documented via claims or administrative data. Moreover, many family caregivers do not self-identify as such, and rather see themselves as a committed parent, child, or spouse. As a result, it can be difficult to assess and quantify not only family caregivers’ needs, but also the underlying support they provide to states’ systems of care for older adults and people with disabilities. States are increasingly using family caregiver assessments to create a more nuanced picture of family caregiver needs. Public health surveys such as the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s (CDC) Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System’s (BRFSS) optional family caregiver module can also provide statewide data. However, these tools are not used routinely.

- Reaching underserved populations: States face additional challenges supporting caregivers from traditionally underserved communities whose members come from diverse racial, ethnic, and linguistic backgrounds, live in rural areas, or are LGBTQ. Resources published by the Diverse Elders Coalition found that over half of diverse caregivers had difficulty translating health-related information into their primary language; that people from racial and ethnic minority communities are less likely to self-identify as caregivers; and that “families of choice” within the LGBTQ community were often not recognized within care systems. Geographically, caregivers in rural areas provide 8 more hours of care a week on average compared to those in suburban or urban settings, and these caregivers have more difficulty finding paid providers and services. These and other barriers can create access challenges both for providers hoping to deliver services, and for diverse caregivers seeking out such services.

In spite of these challenges, states are increasingly supporting services for family caregivers by leveraging key resources (Medicaid, federal grant funding, state dollars), and implementing these resources in ways that maximize benefits to caregivers and align with other state goals and programs.

Recommendations and State Strategies

RAISE Family Caregiving Advisory Council Recommendations: Services and Supports for Family Caregivers

Goal 3: Family caregivers have access to an array of flexible person- and family-centered programs, supports, goods and services that meet the diverse and dynamic needs of family caregivers and care recipients.

- Recommendation 3.1: Increase access to meaningful and culturally relevant information, services, and supports for family caregivers.

- Recommendation 3.2: Increase the availability of high-quality, setting-appropriate, and caregiver-defined respite services to give caregivers a healthy and meaningful break from their responsibilities.

- Recommendation 3.3: Increase the availability of diverse counseling, training, peer support, and education opportunities for family caregivers, including evidence-informed interventions.

- Recommendation 3.4: Expand caregiver support programs and services that maintain the health and independence of families by increasing access to housing, safe living accommodations, food, and transportation, and by reducing social isolation.

- Recommendation 3.5: Encourage use of technology solutions as a means of supporting family caregivers.

- Recommendation 3.6: Expand the use of vetted volunteers and volunteerism as a means of supporting family caregivers.

- Recommendation 3.7: Improve the support of family caregivers during emergencies (e.g., pandemics, natural/human-caused disasters).

- Recommendation 3.8: Increase the prevalence and use of future planning to ensure family members have the needed supports in place throughout the life of the person receiving support.

- Recommendation 3.9: Increase and strengthen the paid LTSS and direct support workforce. (See Section 3b of the RAISE State Policy Roadmap for workforce strategies.)

State Strategies and Promising Practices

1. Medicaid

States have great flexibility, particularly with Medicaid 1115 and 1915(c) waivers, to provide education, training, and counseling to family caregivers who provide increasingly intense and complex care. Over 46% of caregivers provide medical and nursing tasks, with new research indicating greater physical and mental health challenges for caregivers providing these complex services. With many individuals confined to their homes due to the COVID-19 pandemic, reliance on services and supports provided by family caregivers has been greater than ever.

What Types of Training and Counseling Supports Does Medicaid Cover for Family Caregivers?

State training and education, which can include a range of topics and modalities:

- Specified medical equipment

- Medical treatment

- Personal care assistance

- Medications

- Performance of instrumental/activities of daily living or body movements

- Disease pathways or specific conditions

Counseling and other supports, such as:

- Financial support for attending caregiver-related training programs

- Support groups

- Non-psychiatric counseling services

- Caregiver coping skills building

- Consultation services

States require these services to be included in care recipients assessments and/or care plans to be covered.

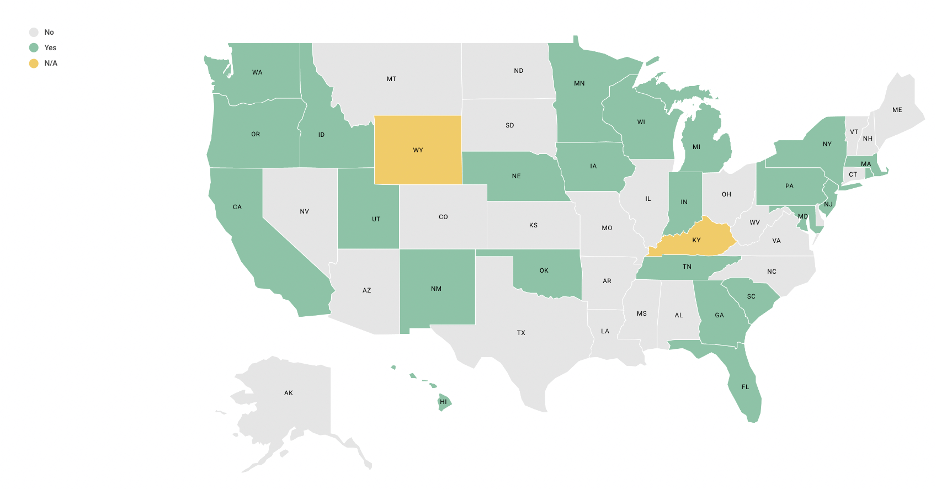

A NASHP environmental scan of states’ Medicaid 1915(c) home and community-based programs for older adults and adults with physical disabilities found that 24 states provide some form of education, training, or counseling to family caregivers.

Family Caregiver Education, Training, and Counseling in Medicaid HCBS

Leverage new funding and flexibility within Medicaid

Recent federal funding represents an historic level of investment in HCBS due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Through ARPA, states may draw down an additional 10 percent federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) for HCBS delivered through March 2022. State plans for spending these additional ARPA dollars provide a window into state priorities moving forward: notably, 30 states propose to use some of this funding to support family caregivers through respite care (12 states), training and education (17 states), and payments to family caregivers (7 states). While this funding is significant, it is short-term and must be spent by the end of calendar year 2024.

State ARPA spending plans represent a significant investment in family caregivers and the care they provide. These plans, which will be updated quarterly, include a range of innovative supports:

- Indiana proposes a caregiver support grant for technology to reduce caregiver loneliness and funding for a gap analysis of family caregiving services.

- Connecticut plans to incorporate supports for caregivers of those with Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias into permanent initiatives. These supports include caregiver assessment, training, respite, care coordination, and the Care of Persons with Dementia in their Environments (COPE) evidence-based support model. The return on investment will be measured via reducing early Medicaid usage, need for paid caregivers, and unpaid caregiver burnout, as well as improving care recipients’ quality of life.

Since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic, CMS has allowed states greater flexibility within state 1915(c) waivers through Appendix K amendments. This policy flexibility resulted in a range of temporary enhancements for Medicaid enrollees and their caregivers during the public health emergency. A NASHP scan of Appendix K amendments found that many states are allowing family caregivers to provide services and receive reimbursement when a hired aide is not available. Six months after the end of the public health emergency, states’ Appendix K amendments are set to end. States will need to assess these flexibilities to determine if they should remain in place for Medicaid beneficiaries and their families.

Reduce overall Medicaid spending and improve care: Washington’s 1115 waiver

Washington’s waiver programs provide additional services to families and are establishing data to better document the return on investment for these programs. The state has successfully reached caregivers of individuals not yet eligible for Medicaid through two programs: Medicaid Alternative Care (MAC) and Tailored Supports for Older Adults (TSOA). MAC supports caregivers of Medicaid-eligible individuals not using Medicaid, and TSOA supports caregivers of individuals not eligible for Medicaid but likely to eventually need Medicaid LTSS. Caregivers of individuals who qualify for these programs are screened using the Tailored Caregiver Assessment and Referral (TCARE) protocol, a tool to assess caregiver needs, and given financial support according to their level of need. Caregivers can spend this money on a wide range of services and supports, including respite, home delivered meals, minor home repairs, training and education, specialized medical equipment, and health maintenance supports, like adult day care and counseling. MAC and TSOA are run under Washington’s Medicaid Transformation project 1115 waiver.

As part of the requirements for its 1115 waiver, Washington has evaluated program cost and quality: a preliminary analysis of key health metrics shows that Medicaid enrollees with families engaged in the program saw a decrease in emergency department visits, hospitalizations, and enrollment in Medicaid HCBS compared to baseline measures. Moreover, surveys conducted with 430 TSOA caregivers and 22 MAC caregivers found high levels of satisfaction with services and a sense of being involved in the support they received.

Washington’s 1115 demonstration waiver was funded by a Delivery System Reform Incentive Payment (DSRIP) initiative which CMS is phasing out. The state is funding a one-year extension (year six) through local intergovernmental transfer funds, which is the plan going forward for a five-year renewal as well.

Support State Rebalancing Efforts

State Medicaid efforts aim for a balance of spending on services in home and community-based settings compared to institutional settings. These rebalancing initiatives are a key focus for states as they navigate current fiscal constraints and envision their future Medicaid service systems. Supporting family caregivers can be an effective rebalancing strategy, as the care they provide allows for a greater number of individuals to remain at home and in the community. Recent research indicates that unmet training needs of caregivers correlated to greater acute care utilization for Medicare home health beneficiaries. Bolstering supports for family caregivers allows for these caregivers to meet the needs of those they serve.

Examples of states that are providing more comprehensive supports to family caregivers through 1915(c) waivers include:

- Georgia’s Structured Family Caregiving program. As part of its 1915(c) Elderly and Disabled Waiver, Georgia provides targeted caregiver supports to unpaid caregivers who live with the Medicaid beneficiary. Services include training, care coordination, and a per diem stipend. Training includes health education, telephonic counseling, and active coordination with care management. The family caregiver receives a minimum of 8 hours of training each year and has the support of other care team members, a health coach, and a registered nurse. Caregivers may qualify for stipends if they are related to the beneficiary biologically and are willing and able to provide care for the beneficiarys assessed needs. Caregivers do not receive stipends for care for a spouse or a minor child.

- Florida’s 1915(b)/1915(c) MLTSS program requires managed care organizations to offer a family caregiver training program as one of several quality enhancements, along with fall prevention in-home and information on end-of-life issues and advanced directives. This program addresses the multilayered financial, emotional, and physical elements of caregiving and outlines the resources available to caregivers in crisis. As described in the waiver, this includes instruction about treatment regiments and other services such as use of equipment specified in the plan of care as well as updates to maintain the care recipient at home. Moreover, Florida managed care organizations are required to establish adequate provider capacity with at least two respite providers serving each rural and urban county of the region.

Address Workforce Shortages through Medicaid Self-Direction

All states use at least one Medicaid self-direction option, which allows beneficiaries to select and pay for direct care aides, including family caregivers, to provide personal care. The extreme shortage of direct care workers is well documented; self-direction can be one strategy for states to both support families and ease workforce shortages in LTSS. State policymakers also note that self-direction can help address disparate access to care in underserved communities, by allowing Medicaid enrollees to choose caregivers from their own cultures and communities or who speak the same language. A NASHP study outlines opportunities and innovations for states to pay family caregivers through their Medicaid self-direction programs.

- California: Extensive use of self-direction as an alternative to out-of-home care. Created in 1974, the In Home Supportive Services (IHSS) program serves over 600,500 low-income older adults and people with disabilities. This Medi-Cal self-direction program allows family caregivers to provide care in the home and receive payment from Medicaid. IHSS is comprised of four programs that each offer special eligibility provisions with a range of personal care, paramedical, and chore services. The first, the IHSS-Residual, provides personal care services for individuals not fully Medi-Cal eligible through a combination of state and county dollars. The second and most utilized program, the Personal Care Services Program, offers services for individuals who are fully Medi-Cal eligible but do not qualify for the Community First Choice Option (CFCO). The third option, the IHSS Plus Option, allows spouses to be eligible providers. The last program, CFCO, is a state plan benefit that provides tailored in-home services and supports for individuals who would otherwise need a nursing facility level of care. This CFCO option also gives states an additional six percent Federal Financial Participation.

- Colorado: Expanding the scope of practice for family caregivers. Colorado’s In-Home Support Services (IHSS) is a participant-directed service delivery option provided in three of its 1915(c) waivers. IHSS is available to both children and adults; parents and other family members are permitted to work as paid attendants. The Medicaid beneficiary or their Authorized Representative may direct their services by hiring, recruiting, training, and scheduling their caregiver (attendant). Attendants are employed by a licensed home care agency that provides 24-hour back-up services, access to a nurse, and Independent Living Core Services. Colorado’s legislature waived the nurse practice act for IHSS; certification and/or licensure is not required for attendants to provide skilled services to the Medicaid beneficiary. The IHSS Agency’s registered nurse provides training and completes skills validation for attendants specific to the beneficiary’s unique health care needs.

Medicaid Supports for Family Caregivers

A NASHP report, Medicaid Support for Family Caregivers, is featured in the RAISE Report to Congress and provides additional information for state policymakers on Medicaid state plan and waiver authorities that can be used to assist family caregivers.

2. Federal Funding

Leverage the Older Americans Act for Those Most in Need

Since 1965, the Older Americans Act has provided funding for services to older people age 60 and older through state agencies on aging, local area agencies on aging (AAA), tribes, and service providers. States can access the Acts funds for Aging and Disability Resource Centers (sometimes called No Wrong Door systems) that provide information and referral to family caregivers and the people that they care for.

Administration for Community Living (ACL) guidance highlights prioritizing low-income older adults, including low-income minority older adults, those with limited English proficiency, and those living in rural areas. States may also identify additional priority populations based on state needs. An example of outreach is incorporated in Colorado’s

State Plan on Aging, which includes an objective of conducting outreach in the principal language spoken by Tribal communities in areas where at least 1% of the population age 60 and older is Native American, or where at least 5% of the state’s Native American population over age 60 lives in the area.

The Act also provides dedicated funding for family caregiver supports through the National Family Caregiver Support Program (NFCSP) that provides grants to states based on their share of the population age 70 and over. States are required to provide a 25 percent match for NFCSP dollars, but they have flexibility to use NFCSP appropriations across different service categories, including counseling, respite, supplemental services, access assistance, and information services. States vary greatly in how they spend this funding. They can tailor it to meet the needs of family caregivers in their states and to blend it with other funding sources.

NFCSP funding, however, is a relatively small amount of money, so states often leverage it with other funding sources. South Carolina, for example, uses its NFSCP funds (80%) to pay for respite services for family caregivers caring for someone age 60 and older as well as older relative caregivers (age 55+) who are caring for a disabled adult or a child (not their own). South Carolina utilizes Lifespan Respite care grant funds (described below) to pay for respite for caregivers of younger populations and to promote respite knowledge and accessibility. It also utilizes the state’s No Wrong Door system to promote access to respite care.

Apply for Other Federal Resources

The Lifespan Respite Care and Alzheimer’s Disease Initiative Programs are funded by ACL and offer grants to states to support people in need and their family caregivers.

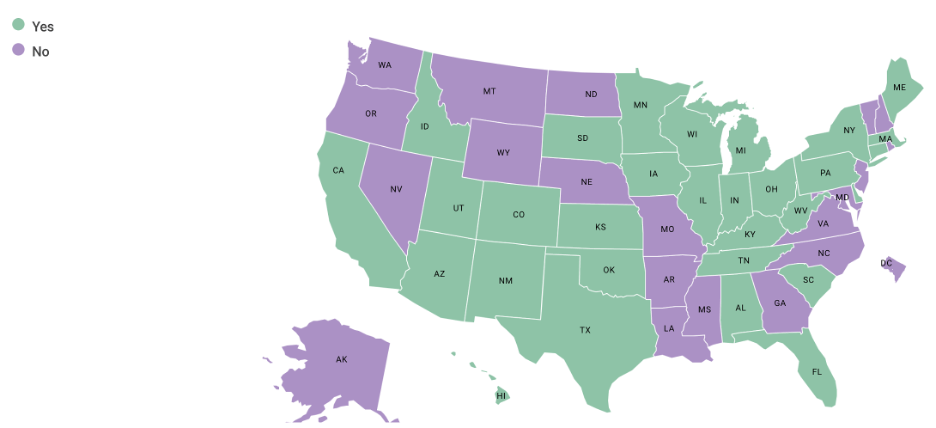

The Lifespan Respite Care Program grants require states to build or enhance coordinated systems of community-based respite care, provide respite services, train and recruit respite care workers and volunteers, provide information to caregivers about available respite and support services, and assist them in gaining access to services. Qualifying state agencies must work in concert with an Aging and Disability Resource Center and commit to collaborate with their state’s respite care coalition. Since 2009, 37 states and the District of Columbia have received Lifespan Respite Grants.

Created in 2018, the Alzheimer’s Disease Programs Initiative (ADPI) grant program funds states, communities, and Tribal entities to support HCBS for those with Alzheimer’s Disease and Alzheimer’s Disease Related Dementias (AD/ADRD). This grant also supports the creation of public and private cross-sector partnerships to meet the needs of individuals with AD/ADRD and their caregivers. As of 2020, over 37 states and the District of Columbia have received ADPI grants to specifically support diverse racial and ethnic communities.

States have used these grant funds in a myriad of ways to address the particular strengths and gaps within their states:

- Montana: Dementia care navigators. Montana’s Department of Public Health Services Senior and Long-Term Care utilized ADPI funds to train Aging Disability Resource Center/Area Agency on Aging personnel to beDementia Care Navigators. These Navigators utilize an evidence-informed tool, the Alzheimer’s Navigator®, to assess care needs, provide care consultation, and disseminate service referrals for individuals with AD/ADRD and their caregivers. Additionally, Montana utilized the ADPI grant to expand the respite voucher program in its pilot grant areas and include more allowable items in their assistive technology services, including weighted blankets and robotic pets.

- New York: Expanding respite workforce and service access. The state has established a robust, cross-sector service directory. The NY Connects Resource Directory, which is part of New York Connects’ No Wrong Door system, provides statewide information and assistance to individuals across age and disability types, their caregivers, and professionals. One of the New York State Office for the Aging’s objectives for its 2020-2023 ACL Lifespan Respite Grant cycle is a grant program to test a new respite training curriculum for respite providers. New York is currently piloting an online respite worker training that embeds ARCH’s Respite Care Professional Core Competencies (see text box below for more information) that will result in respite training certification and the development of a respite provider directory. Additionally, six mini grants were awarded to organizations across the state to train volunteer respite workers using an in-person training curriculum.

- South Carolina: Coordinating respite care funding. In 2013, the state issued a plan with an environmental scan of respite care services and recommendations for sustainable lifespan respite. In 2018, this State Committee on Respite published An Update on Sustaining South Carolina’s Family Caregivers through Respite. As a result, they have secured recurring state appropriations for respite vouchers for caregivers. State funds for respite increased in FY2018 to $2.4 million as a recurring line item for respite and $900,000 for respite for families caring for someone with Alzheimer’s disease or a related disorder. These amounts have remained stable. South Carolina has also utilized grant funds for educational purposes, including the development of respite informational videos, infographics, and a physician-directed caregiver identification/assessment tool. South Carolina’s mini-grants to six churches developed “break rooms” for respite for family caregivers in their congregations/communities. Through an ACL funded project, South Carolina Department on Aging has partnered with the Women’s Missionary Society of the African Methodist Episcopal Church to offer caregiver education and respite to families living with dementia in 16 rural counties. The leadership and state plan have helped with the coordination of respite funds from several programs—the State Voucher Program, Alzheimer’s Disease, Family Caregiver Support, and Lifespan Voucher Programs—to ensure access to families across the lifespan.

Respite Workforce: Promoting Best Practices and Building State Capacity

NASHP, in partnership with the ARCH National Respite Network and Resource Center and with support from ACL, are collaborating on a three-year project to promote best practices and build state capacity for respite care. The goal of this project is to support and foster state and national efforts, including those of the RAISE Advisory Council, to increase access to respite for family caregivers by:

- Developing, testing, and scaling a respite workforce recruitment, training, and retention program

- Hosting a state summit on family caregiving

- Conducting state scans on respite and direct care workforce policy activity

- Featuring case studies and promising practices

Demonstration sites in Arkansas, Illinois, Kansas, Massachusetts, Montana, Nevada, New Mexico, New York, Oklahoma, South Carolina, and Wisconsin are piloting the respite workforce recruitment, curriculum, and evaluation.

More information can be found at NASHP’s RAISE Family Caregiver Resource and Dissemination Center website.

3. State Funds

While entirely state-funded programs are constrained by state budget capacity, these programs can be more closely tailored to the needs of residents of that state and provide additional examples of state innovation.

- California: Caregiver Resource Centers. In 1984, the state legislature established California Caregiver Resource Centers (CRCs) throughout the state. These 11 centers provide uniform services: family caregiver assessments, information, care navigation, training, counseling, respite care, and legal and financial consultation. They serve caregivers of persons with adult-onset cognitive impairments, with the majority reporting Alzheimer’s and related dementias, followed by stroke, Parkinson’s disease, head injuries, and other impairments. In FY 2019-20, the legislature secured an augmentation of $15 million per year to enable the CRCs to implement multiple technologies in order to expand and scale many of its services and report to the state Department of Health Care Services. In FY 2020-21, the CRCs served over 16,000 caregivers, of which 6,000 were first time service users with the remaining 10,000 as returning clients. The state general fund is providing $10 million for these services for FY 2022-2023. Each center operates as a nonprofit and is also funded by county contracts, private grants, and donations. Many of them also receive funding from the Older Americans Act and its Family Caregiver Support Program.

- Minnesota: Focus on local/community needs. Minnesota supports HCBS through its Live Well at Home grant program, which is funded by the state and administered by the Department of Human Services. Live Well at Home grants are given to local organizations that work to promote healthy aging at a community level by helping older adults remain in their homes. Organizations can apply for grants to advance these goals through caregiver supports and through other measures that facilitate caregiving (e.g. helping with daily tasks, providing rides and meals, modifying homes, and providing other supports to older adults). Minnesota funds on average 40-50 organizations throughout the State for a total of $8.1 million. For the 2022 grant cycle, 17 of the 42 total grantees specifically mention caregivers in their main focus, with supports including respite, caregiver training, caregiver emotional support, and care coordination. The funded organizations cover all of Minnesota’s geographic regions. Grantees vary in size and in the primary community they serve, with some focusing on service to veterans, people with unstable housing, and people of different cultural groups.

- New York: Supporting people with dementia and their caregivers. With legislative approval, the Alzheimer’s Disease Caregiver Support Initiative is funded at $25 million annually with state funds to promote early diagnosis and provide education, care consultation, and a plan for medical and social services. Teaching hospitals and regional providers receive funding to improve medical care and social services for people living with Alzheimer’s disease and their caregivers.

- North Dakota: Addressing need in rural areas. Prompted by North Dakota’s high percentage of residents living in frontier counties and rural areas with limited access to direct care workers, theService Payments for the Elderly and Disabled (SPED) program allows payments to family caregivers for services including personal care, homemaker services, and chores (including snow removal and heavy cleaning). SPED is funded entirely by state general funds, which allows North Dakota to determine eligibility Eligible individuals do not need to live with their caregiver to receive most SPED covered services. SPED also covers home modifications, case management, and respite. Financial eligibility is based on countable income and assets. Some eligible individuals may have a cost share based on a sliding fee schedule. Individuals eligible for Medicaid are first referred to Medicaid. Participants must have liquid assets, which excludes the value of one’s home among other considerations, under $50,000 to qualify.

Dementia and Caregiving

The Alzheimer’s Association and CDC’s Healthy Brain Initiative State and Local Public Health Partnerships to Address Dementia: The 2018-2023 Road Map (Road Map) charts a course for state and local public health agencies and their partners that prepares all communities to act quickly and strategically by stimulating changes in policies, systems, and environments. The Road Map provides an agenda of 25 actions that support dementia risk reduction, early detection of dementia, preventable hospitalizations for those with dementia, and caregiving for those with dementia. In addition, the CDC through the Building Our Largest Dementia (BOLD) Infrastructure Act funded the University of Minnesota in 2020 to establish the first Public Health Center of Excellence (PHCOE) on dementia caregiving. This PHCOE was established to promote dementia caregiving as a public health issue, gather and translate evidence and best practices, and provide technical assistance to health departments to support changes to systems, environments and policies that support the important role of dementia caregiving. The CDC through BOLD also funds 23 state, local, and tribal cooperative agreements with public health departments to promote a statewide, comprehensive approach to address dementia and to align their activities with the Road Map.

Key Takeaways

- Given the more than 53 million family caregivers, funding for supports and services that are specifically targeted for them is very limited, so states blend funding from the different federal, state, and local sources.

- States do not have an adequate supply of direct care workers to meet the needs of older adults and people with disabilities. Funding family caregiver supports and services, especially Medicaid consumer-directed programs, can be an effective policy strategy to expand workforce capacity to enable people to live in the community.

- While this roadmap focuses on specific family caregiver services, successful family caregiving assumes a well-integrated, person- and family-centered care system that integrates the caregiver into care processes and health care systems.

- States need better data to monitor, track, and evaluate the impact of government-funded services and supports for family caregivers. A NASHP review of about 800 recommendations from 27 key family caregiving reports found that standardized quality of care and quality of life measurements — particularly pertaining to HCBS and family caregiver outcomes — and evidence-based interventions are evolving.

- Family caregivers are generally a safety net of support. In addition to funding, states can play a critical role reaching underserved caregivers — especially in multicultural or immigrant communities and with family caregivers from non-English-speaking backgrounds — allowing more family caregivers to access the programs and services featured in this section of the roadmap.

About This Roadmap

The purpose of this roadmap is to support states that are interested in developing and expanding supports for family caregivers of older adults by offering practical resources on identifying and implementing innovative and emerging policy strategies. Although families care for people across the lifespan, the focus of this roadmap is on policies, programs, and funding for family caregiver of older adults.

NASHP created this roadmap with guidance from policymakers and leaders from across state government, using the RAISE Act goals and recommendations as a framework. Congress enacted the Recognize, Assist, Include, Support and Engage (RAISE) Family Caregivers Act in 2018, which created an advisory council to develop the country’s first national Family Caregiver Strategy. With support from The John A. Hartford Foundation and in coordination with the U.S. Administration for Community Living, NASHP’s RAISE Family Caregiver Resource and Dissemination Center aims to support states as they develop policies to address family caregivers.

The RAISE Family Caregiving Advisory Council recently published its five goals and 26 recommendations which highlight ways that states can better support family caregivers. In alignment with the Council’s work, the roadmap is organized into the following sections as a series:

Section 1: Public Awareness and Outreach to Family Caregivers

Section 2: Engagement of Family Caregivers in Healthcare Services and Systems

Section 3: Services and Supports

Section 4: Financial and Workplace Security for Employed Family Caregivers