The Basics: Why Do States Need New Capacity to Address Consolidation?

Why Address Consolidation?

Evidence suggests that vertical integration and growing consolidation in health care leads to higher hospital and provider prices and higher total spending — all while having little to no impact on improving quality of care for patients, reducing utilization, or improving efficiency. A 2021 study also found that mergers that significantly increase hospital concentration result in slowed wage growth for hospital workers. Beyond the consolidation of providers, there is also increasing concern about the consolidation of carriers, pharmacy benefit managers, and other entities within the health care payment chain. There is growing interest across states to lower health care costs by addressing this consolidation and vertical integration as a root cause for rising health insurance premiums and greater out-of-pocket consumer costs. Additionally, state officials have shared concerns that consolidation can have important access and quality implications that state officials want to monitor more closely.

How to Address Consolidation

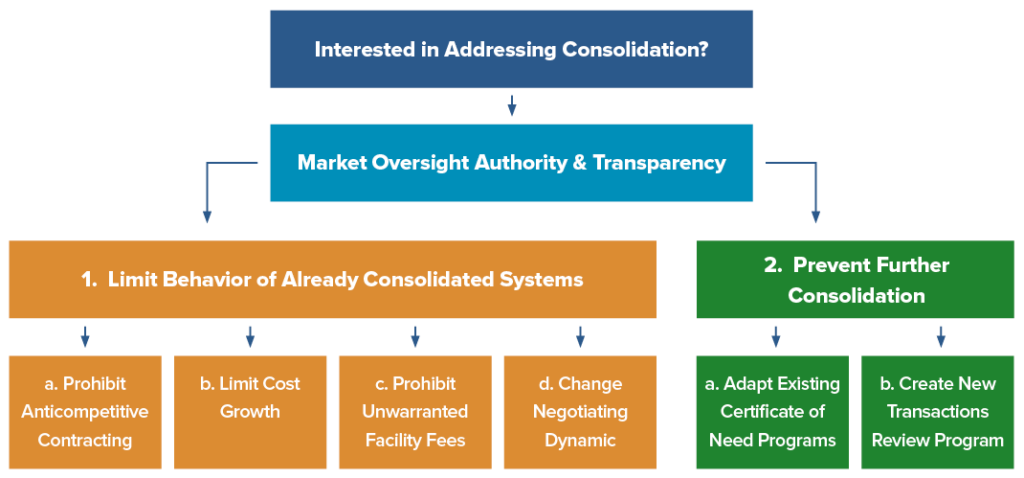

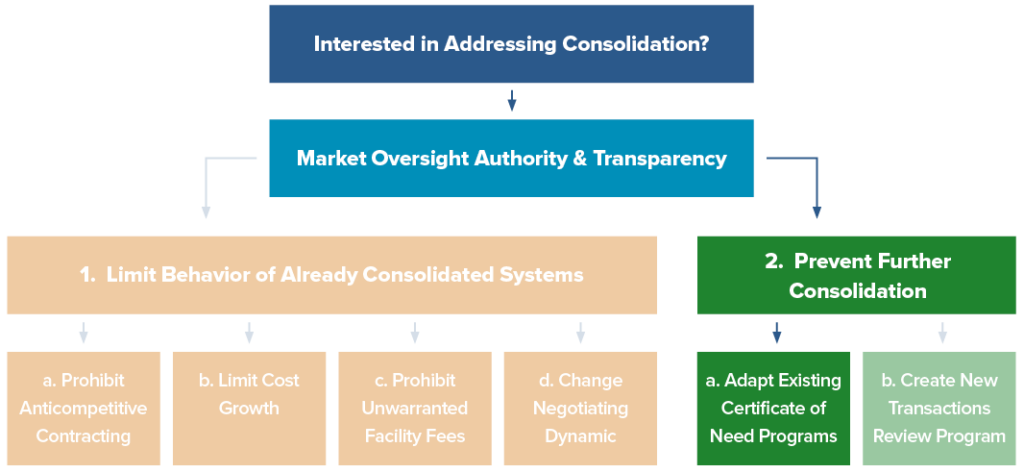

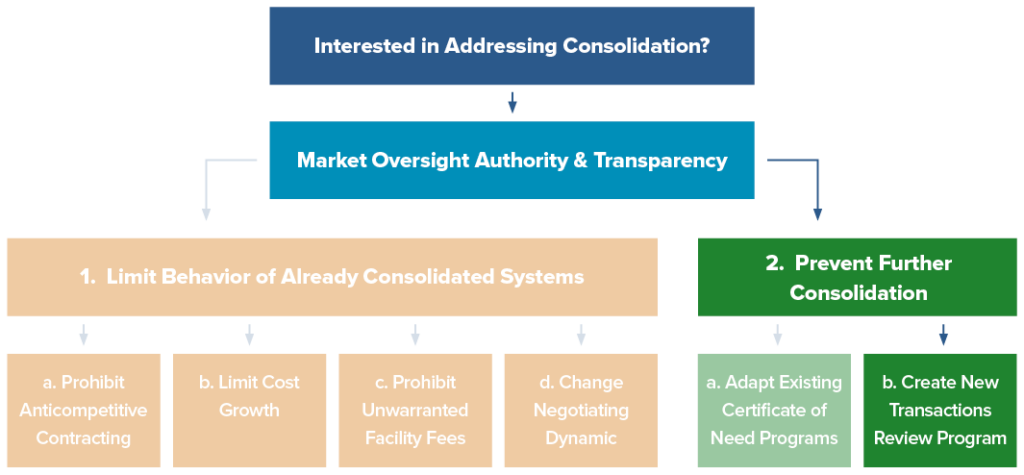

Addressing consolidation could take the form of: 1) limiting the anticompetitive behavior of already consolidated systems and/or 2) preventing further consolidation. Either of these efforts will create or build upon existing market oversight authority and be enhanced by robust transparency programs. NASHP developed a series of model legislation that can help states gain better oversight over consolidated systems — addressing the first branch in the graphic below. Prohibiting anticompetitive contracting terms, limiting unwarranted facility fees, limiting cost growth, and changing the negotiating dynamic between insurers and hospitals are all mechanisms to contain costs, recognizing that the market is largely concentrated and integrated across levels. Beyond trying to limit existing consolidated systems, states can prevent further consolidation via the second branch in the graphic below: giving an office or agency broader authority to review proposed transactions and, when appropriate, stop or modify the transaction to protect consumers.

What about Existing Federal and State Authorities?

A variety of state and federal offices already have some oversight over consolidation and health care transactions. Federal authorities have historically focused on horizontal mergers, or mergers involving two hospitals in the same geographic area, using anti-trust laws. However, health care consolidation increasingly occurs through transactions that evade this oversight. In particular, physician practice acquisitions by hospitals, health plans, or private equity investors are typically too small to be reported to federal antitrust agencies under the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act.

Under existing state law, state attorneys general can file lawsuits alleging a transaction violates state or federal antitrust laws. However, to block a merger, a state attorney general must expend significant time and resources to convince a court that the merger will “substantially lessen competition.” Because this can be so resource intensive, attorneys general can typically only challenge the largest, most problematic mergers. Additionally, state attorneys general may not be aware of all proposed mergers or transactions, particularly for smaller scale transactions. Many state officials report they are unaware of smaller mergers and acquisitions that over time can cause significant changes across their health care markets.

In addition to filing lawsuits, states have some existing authority to review changes in the health care market, particularly under certificate of need (CON) programs that require a hospital or health system to obtain approval from a state agency or board before expanding, discontinuing, or dramatically changing health care services. However, state programs may need further authority and resources to be effective at blocking or modifying concerning mergers.

Policy Building Blocks: How to Build Effective State Oversight of Consolidation

What Does Strong Pre-Transaction Review Look Like?

Whether bolstering an existing certificate of need program or creating a new market oversight office, state efforts to review transactions should grant a state office or agency with additional authority to review the impact of consolidation on health care costs, among other factors. When building capacity for new oversight, state officials should consider:

- Establishing an administrative review process in which health care entities are required to provide notice of proposed transactions. In many cases, state officials may not be aware of an ongoing transaction, making it difficult to challenge on the state level or to alert federal antitrust enforcers. Establishing a notice requirement allows state officials to more effectively oversee cumulative, smaller transactions that may amass market power over time.

- Providing authority to approve, reject, or place conditions on proposed transactions with an explicit eye toward overall health system and individual consumer costs. Creating an administrative review process allows states to examine and challenge transactions based on broader criteria than anti-trust laws. For instance, state officials can more easily impose conditions on a transaction, such as maintaining access to emergency services, through an administrative review rather than through antitrust litigation. Although states could avoid costly legal proceedings, this type of review may still be resource and time intensive.

- Covering health care transactions at values below the federal threshold and all types of consolidation, including horizontal, vertical, or cross-market. Requiring all providers to give notice to an office overseeing health care costs or to the attorney general means that state officials will at least be aware of and able to track ongoing consolidation and its implications. State policymakers may choose to narrow which types of transactions are subject to a streamlined versus more robust review process, but a baseline notice and review requirement ensures state officials are aware of even smaller changes to the local health care market.

- Ensuring state authorities have access to and expertise with appropriate data and analytics. State reviewers should be able to conduct a thorough review of the impacts of the proposed transaction on health care prices, overall state spending, and market functioning, including equity and quality outcomes for patients. As seen below, some states, such as New York and Oregon, consider the equity impacts of a transaction. The state should also be able to request data (e.g., revenue and volume shares, historical expansion, discharges, physician staffing, etc.) and other information (e.g., internal policies, organizational charts, and term sheets) from merging entities. The data and review requirements could be refined based on state priorities, but states could look to Massachusetts, Connecticut, Oregon, and New York for examples.

- Establishing a sustainable funding stream for the state to conduct its own analysis of proposed transaction impacts. State reviewers should have reliable funding to cover their work or the costs of a state-selected consultant to help with analysis. Otherwise, the agency may rely on fees from merging entities to pay for analysis, which may not be sufficient to fund regular agency functioning. Relying on merging entities to hire outside consultants could lead to biased or conflicting information.

- Including the authority for post-transaction monitoring and follow-up reports on approved transactions. State officials may want to monitor the effect of an approved transaction on the market and for compliance with any imposed conditions. This could include the authority to contract with consultants to monitor compliance. Additionally, states could require reporting from the health care entities at certain intervals after a transaction to watch for other cost, quality, or access impacts that may necessitate further policy action.

How Can States Consider Equity Impacts of Transactions?

New York

- How will access improve and disparities be reduced, particularly for medically underserved groups (MUGs)?

- How will utilization of care by MUGs be impacted?

- Will the applicant meet its uncompensated care, community services, and civil rights obligations?

- Will care be provided to low-income publicly insured, and MUGs?

- How physically accessible (via transportation) will care be?

- How will communication barriers be addressed for patients with limited English-speaking and speech/hearing/visual impairments?

- How will architectural impairments be addressed for patients with mobility impairments?

- Will quality improve or be maintained?

Oregon

- How will access improve and disparities be reduced, particularly for medically underserved groups (MUGs)?

- How will utilization of care by MUGs be impacted?

- Will the applicant meet its uncompensated care, community services, and civil rights obligations?

- Will care be provided to low-income publicly insured, and MUGs?

- How physically accessible (via transportation) will care be?

- How will communication barriers be addressed for patients with limited English-speaking and speech/hearing/visual impairments?

- How will architectural impairments be addressed for patients with mobility impairments?

- Will quality improve or be maintained?

How Can States Establish Greater Pre-Transaction Review?

Weighing these responsibilities and core competencies, states may consider a few places within state government to build out the responsibility to oversee proposed health care transactions rather than creating something new. States with existing certificate-of need programs might expand their current program or choose to establish a new program focused exclusively on market oversight.

Bolstering Existing State Certificate of Need Programs (Path 2a)

Why Start with CON?

CON programs may be an appropriate starting point to build capacity to review proposed transactions. CON programs were originally designed to, and many still do, receive some notice of proposed changes to the health care market and have the infrastructure to receive and process applications from health care entities. This means state CON offices may be well-positioned to take on more oversight work.

However, CON offices will likely need greater authority and resources to be truly effective. Borne out of an interest in health planning, CON programs traditionally have been more focused on the distribution of health care services, rather than on the affordability of care or impact of market changes on cost. Each state CON program varies by what type of provider activity triggers a mandatory review and which activities might require approval by a state CON board or office.

Considerations for Expanding CON

If a state is interested in expanding the authority of a CON program, it should consider making changes to the program, including:

- Establishing additional resources for the CON office, which could include creating a more sustainable funding stream, hiring additional staff support, providing authority to collaborate with other state agencies, and paying for access to new data sources

- Ensuring an explicit focus on cost and affordability of care, which could be combined with other explicit focuses such as health equity

Creating sufficient oversight authority over transactions, including the ability to reject, approve, or approve and place conditions. The office should also be able to conduct post-transaction reviews.

Potential Challenges to Building Off CON

While CON programs are a natural starting point for building state capacity to review problematic health care transactions, it would require a state to pivot older, at times pared-down programs (i.e., some CON only focus on long-term care nursing facilities), to focus on a new purpose. CON programs may be politicized in some places, and interested groups may be opposed to traditional CON programs, creating challenges for establishing a reformed version with increased oversight authority. Additionally, a CON program will only be successful in overseeing proposed transactions if it has access to and expertise in analyzing the health care market and cost data submitted by health care entities. Building those capabilities can be very challenging because of resource constraints. In a few states, this expertise may reside in another agency.

Finally, CON programs have traditionally had different goals in reviewing changes to the health care market other than lowering health care costs and slowing down consolidation efforts. After the initial goals for CON programs were outlined by the federal government, programs evolved to focus on goals such as ensuring public participation in the development of new health care facilities; preserving or improving the quality of care; and addressing the maldistribution of resources in a state. States may want to maintain some of these goals while building on or shifting traditional CON programs.

Example of State CON Program

Massachusetts has one of the most robust CON programs, called a “determination of need” (DoN). Providers must file a DoN application with the Department of Public Health (DPH) when they plan to make substantial capital expenditures, make substantial changes in services, change ownership, or make other specific operational changes. DPH can then approve or reject applications. DPH’s review capacity is supplemented by the Health Policy Commission’s (HPC) ability to review and comment on DoN applications as a party of record. The HPC also has a separate process for reviewing proposed provider affiliations, discussed below. The HPC is an independent state agency charged with monitoring health care spending growth in Massachusetts. Through HPC’s work monitoring spending growth for the state’s cost growth benchmark, the agency has established strong data analysis capabilities and insight into the Massachusetts health care market.

In one recent example, Massachusetts used the DoN process to analyze the spending impacts of a proposed health system expansion, renovation, and improvement. In early 2021, Mass General Brigham (MGB) filed DoN applications for three substantial capital expenditures, totaling $2.3 billion, including the expansion and renovation of Massachusetts General Hospital and Brigham and Women’s Faulkner Hospital, as well as the creation of three new ambulatory sites across the state. In its public comment in the DoN process, the HPC found that the expansions were likely to increase yearly commercial health insurance spending in Massachusetts by $46 million. Two of the applications were eventually approved with conditions, and MGB withdrew one proposal after DPH staff recommended that the application was “not consistent with the Commonwealth’s goals for cost containment.”

Establishing a New Office or Program Focused on Health Care Market Oversight (Path 2b)

Why Create a New Program?

As an alternative to expanding an existing CON office, states may consider creating an entirely new office or a new program within an existing separate state agency to oversee transactions. States may be interested in establishing a new program to review transactions if the state no longer has a CON program in place or if another agency or office has experience regulating the health care market.

For example, in some states, there may be an agency that is a centralized place for health policy development, strategy, and cost oversight. Additionally, there may be an office that has access to data tools to analyze the impacts of a transaction but that does not have the same application and transaction review process in place as a CON program. In these cases, policymakers may want to leverage these existing capacities but task the agency with new oversight responsibilities.

Considerations for Creating a New Program

NASHP’s model legislation to improve market oversight grants state attorneys general and state health officials with overarching authority on cost, such as a health cost commission, and the authority to review, place conditions on, and block potentially harmful consolidation of health care providers[1] in their state. The model legislation creates a comprehensive review process for transactions that have the potential to reduce access, increase costs, or otherwise are not in the public interest.

The model addresses gaps in federal antitrust enforcement because it would require state review of health care transactions at values below the Hart-Scott-Rodino Act threshold and apply to all types of consolidation, including horizontal, vertical, or cross-market. The model is designed to answer key questions for a transaction oversight program, including:

- Which hospitals or providers are covered?

- What does the state’s review process entail?

- How is the review process funded?

- What approval authority does the attorney general possess?

- What kind of enforcement or post-approval monitoring is necessary?

Additionally, if a state with an existing CON program creates an alternative oversight office, state policymakers may wish to consider how these programs communicate or identify and manage instances of potential overlap. Regular cross-team check-ins and information sharing can foster coordination and limit redundancies, particularly where staffing is limited and multiple reviews may be required of merging entities. States can also leverage the creation of a new oversight agency as an opportunity to update CON rulemaking.

Examples of State Transaction Oversight Programs

Massachusetts law requires any provider organization making material changes to its operations or governance structure to report to the state’s Health Policy Commission (HPC) for review before completing the transaction. Such changes include mergers, acquisitions, contracting affiliations, joint ventures, affiliations between a provider and a payer, the formation of a new contracting entity, and strategic clinical affiliations. The HPC examines potential impacts of the transaction on costs, market functioning, quality, access, and equity for Massachusetts consumers. While the HPC lacks the authority to block or condition a transaction, it is empowered to conduct a cost and market impact review (CMIR) of transactions likely to significantly affect costs or market functioning and can refer its CMIR report to the attorney general or other state agencies for further action on behalf of consumers.

In 2021, the Oregon legislature passed a law that gives the Oregon Health Authority the ability to review and block many mergers of health care providers and other health care entities that have the potential to negatively affect access to health care in the state. Through the newly created Health Care Market Oversight program, the agency ensures that future health care consolidation supports statewide goals related to health equity, lower costs, increased access, and better quality. Some states already have an administrative process to review transactions involving health care providers. For example, the Office of Health Strategy in Connecticut must approve transfers of ownership of hospitals and large physician group practices, among other transactions. Best practices from these states and others are included in the NASHP model act.

Alternative Approaches to Health Care Market Transparency

As discussed, one benefit from health care market oversight programs is transparency and insight into changes in local health care markets that may affect access and affordability. Given this need, some states have proposed and/or enacted legislation to require reporting on health care transactions without the added authority to review and approve or reject a proposal. While this gives less authority to a state agency, it could be an important first step in an iterative approach to addressing health care consolidation.

Nevada has a limited CON program focused exclusively on new facilities proposed in rural areas. In 2021, the legislature enacted two bills to provide state officials more insight into changes to, and specifically consolidation of, the health care market. Nevada AB 47 requires physician group practices of two or more physicians to notify the attorney general and insurance commissioner at least 30 days before a “reportable health care transaction.” The information will be held confidential, but the attorney general can investigate, if appropriate. Nevada SB 329 requires hospitals and physician groups to notify the Department of Health and Human Services of any merger, acquisition, or joint venture no later than 60 days after a transaction is finalized. The department does not have the authority to stop a transaction, but this measure may provide greater transparency.

Legislators in Florida proposed a similar bill in 2021. Although not enacted, this measure would have required entities to report certain information to the attorney general if a health care transaction would create a monopoly. The notice requirements would have provided a mechanism for the Office of the Attorney General to review transactions before they occurred to determine whether a proposed transaction had antitrust implications and, if warranted, pursue action to prevent coercive monopolies from forming in the health care market.

Most recently, New York’s enacted budget includes a new requirement for health care entities to provide 30 days of notice to the Department of Health of certain “material transactions,” including acquisitions, affiliations, mergers, and the formation of joint ventures. While the state will not have the authority to reject or modify transactions, it will give the Department of Health the ability to collect data and assess changes to the market with health equity in mind, consistent with the state’s CON program review criteria.

Complementary Tools and Policy Limitations

NASHP’s model to improve health care market oversight, created with diverse state guidance and input, is a valuable strategy to reduce harmful health care consolidation and limit the associated cost and quality impacts for consumers. While improved transaction oversight is one tool to lower health care costs, health care markets are largely already consolidated across the U.S. To fully address rising health care costs, states may consider additional complementary policy tools, particularly policies that seek to curb the anticompetitive behavior of already consolidated powerful health systems.

NASHP has other model legislation on using insurance rate review to control costs, increase hospital financial transparency, prohibit unwarranted facility fees, and limit anticompetitive provider contracting. As seen below, identifying the right policy tools requires first identifying which “cost drivers” should be addressed. Establishing greater oversight of health care transactions is one potential tool in state toolboxes. As these issues are interwoven, these different policies complement one another and can be used together to combat the many contributors to high costs.

Endnotes

1. In NASHP’s model legislation, “health care provider” means any person, corporation, partnership, governmental unit, state institution, or any other entity qualified or licensed under state law to perform or provide health care services. Health care services includes supplies, care, and services of medical, behavioral health, substance use disorder, mental health, surgical, optometric, dental, podiatric, chiropractic, psychiatric, therapeutic, diagnostic, preventative, rehabilitative, supportive, or geriatric nature. States could structure definitions of provider and health care services depending on targeted level of oversight.

Acknowledgements

This brief was developed with support from model legislation and white papers coauthored by Katherine L. Gudiksen, PhD, MS, The Source on Healthcare Price & Competition, and Erin Fuse Brown, JD, MPH, Center for Law, Health & Society at Georgia State University College of Law.

This policy brief and the accompanying model legislation were produced with support from Arnold Ventures.