Members of his congregation kept going to the hospital with diet-related issues, Reverend Dr. Heber Brown, III, realized.

“I got tired of praying and hoping they made it and walked out,” Reverend Brown realized. And then…

“I got tired of praying and hoping they made it and walked out,” Reverend Brown realized. And then…

“God gave us an idea and vision to be proactive on the issue of health in our congregation,” Rev. Brown explained to us yesterday on Day 2 of Real Chemistry’s Health Equity Summit.

This was the seed for the Black Church Food Security Network, planting a pragmatic vision for health and well-being weaving together local food, civic empowerment, economic development, and faith.

“We had a little piece of land in front of our church,” the Reverend realized. “God gave me a vision to use land to start growing what we needed to foster and encourage physical health in our congregation.”

Those 1,500 square feet of land now yield about 1,200 pounds of produce every year including broccoli, tomatoes, herbs, summer squash, and watermelon, among other nutritional food from Mother Earth.

That front-yard garden made a difference at the Pleasant Hope Baptist Church of Baltimore. The plants grew, then once mature were cleaned in the church kitchen and provided to members of the community. That church kitchen often included the food grown in meals cooked there.

That front-yard garden made a difference at the Pleasant Hope Baptist Church of Baltimore. The plants grew, then once mature were cleaned in the church kitchen and provided to members of the community. That church kitchen often included the food grown in meals cooked there.

And the community members saw first-hand how growing their own food fostered health in their church and neighborhood.

“That was the primary vision,” Rev. Brown said. But “God gave another vision.”

Here’s where Dr. Brown’s community organizing skills evolved one vision into three.

It was all about scale. “If we were able to experience this kind of benefit and blessing getting closer to our food source at this one church, what if we could get multiple churches to grow food on the land that they owned?” he wondered.

Thus emerged the Black Church Food Security Network, growing from one church to many.

It’s important to place this story in the context of what was happening in Baltimore at the time: the Network evolved in the middle of the Baltimore uprising which followed the death of Freddie Gray.

As the Washington Post reported, “Baltimore was added to a growing list of cities — Ferguson, Mo., and New York among them — in which Black people died at the hands of police, unearthing years of simmering distrust and animosity.”

The Pleasant Hope Baptist Church was located at the “epicenter of demonstrations,” Rev. Brown said. During this time, people in the community went hungry: grocery and food stores were shut, and schools closed for a time (so students could not access the important breakfast and lunch nutrition programs so important to children’s health in many communities).

The Pleasant Hope Baptist Church was located at the “epicenter of demonstrations,” Rev. Brown said. During this time, people in the community went hungry: grocery and food stores were shut, and schools closed for a time (so students could not access the important breakfast and lunch nutrition programs so important to children’s health in many communities).

Rev. Brown called on his farmer friends to truck food into Baltimore, and they loaded up the church bus and drove food around the city in the midst of the uprising.

From one church garden planted five years ago, to today — a connection grown between farmers, Black churches, and the community with three programs all addressing health and wellbeing:

- Operation Higher Ground. This is the church garden initiative, focused on African-American congregations and the land they own for growing gardens. The program consults with churches, many of whom have congregation members who grew up in the south or have family roots there farming together on the land. Rev. Brown has seen the program awaken “warm, fuzzy feelings about growing food” hearkening back to peoples’ family histories. “We are helping people in the north flash back to a time when we grew our own food,” he realized.

- Farmers’ Markets. On Sunday’s after prayer services, the Pleasant Hope Baptist Church hosts mini-farmers’ markets – “think farmers’ market inside a church,” from “soil to sanctuary.” Typically, after church congregants go to eat somewhere, Rev. Brown told us. The mini-market is set up in the fellowship hall or multipurpose room, featuring produce and gifts and “goodies from Black farmers and business owners.” This market is an experience mashing up the market goods, a DJ, music and dancing, food demonstrations, and of course, fellowship.

- The Arc Initiative. Rev. Brown conjured up Noah for this third pillar, as in “building an ark.” This program supports co-creating community-led food systems that are hyper-local, in touch and in tune with the character of local communities as the Reverend described. This is the scaling of Operation Higher Ground, to other Black churches in other towns.

Together, the mission of the three programs is to anchor with other Black churches in partnership with Black farmers….a group that has been discriminated against and kept from opportunities, long marginalized and overlooked, Rev. Brown called out.

In the future, he envisions the mesh of the food system with the health system. The pandemic has stretched the food system to its fragile limits, dependent on corporate food conglomerates whose supply chains were broken in the public health crisis.

The key learning: in this moment, to create small local food systems and, in the Reverend’s words, “nourish a dynamic food environment that interlocks with other food systems from other communities.”

For example: “What if the Baltimore food system connected with the Philly area food system, the Brooklyn system, and up and down the interstate?”

Ultimately, that is the vision to move forward: not one Big Food conglomerate system but smaller ones led by those most directly impacted by food insecurity and food apartheid, Rev. Brown described.

That’s the power to help lean into to a healthier community for all of us, he envisions.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: At the basis of health are basic needs, social determinants, that set the stage for each of us humans: education, clean environments (air, water, housing), safe neighborhoods, financial and job security, and of course, food that’s nutritious, accessible, and affordable.

Health Populi’s Hot Points: At the basis of health are basic needs, social determinants, that set the stage for each of us humans: education, clean environments (air, water, housing), safe neighborhoods, financial and job security, and of course, food that’s nutritious, accessible, and affordable.

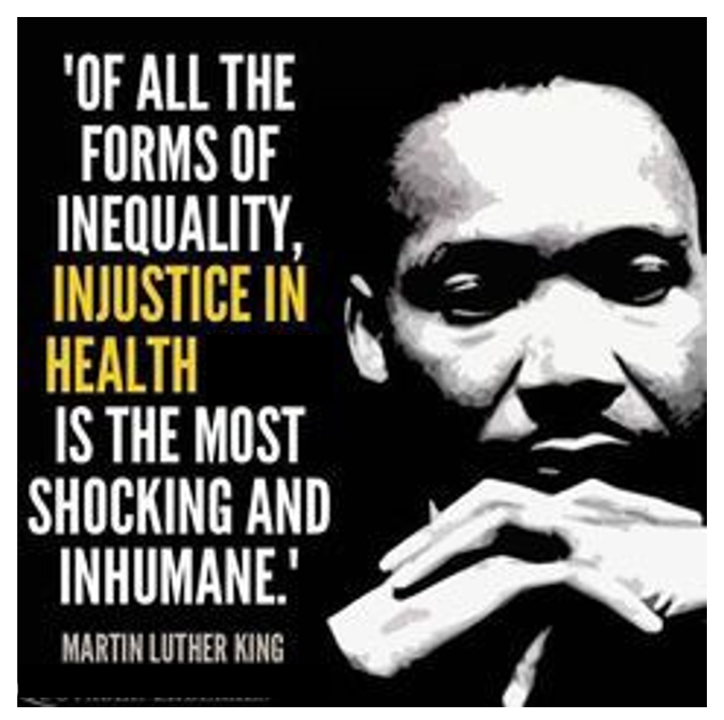

As we approach the next Martin Luther King, Jr., Day, we reflect on this voice for the Civil Rights Movement calling out racial discrimination in State and Federal Law.

Among the many forms of inequality, “injustice in health is the most shocking and inhumane,” King said in a press conference before a speech he gave on March 25, 1966 at the second convention of the Medical Committee for Human Rights (MCHR).

This statement is often quoted with the words “health care” instead of “health.”

While health care services contribute to peoples’ overall well-being, it is those social determinants — education, clean water, food — that contribute even more mightily to one’s overall, holistic health.

Following the death/murder of George Floyd in 2020, Dr. Donald Berwick wrote about The Moral Determinants of Health in JAMA.

In this impactful essay, Dr. Berwick (the brilliant mind behind the Triple Aim and other health care innovations) explained that health for all in American will not happen….

“Unless and until an attack on racism and other social determinants of health is motivated by an embrace of the moral determinants of health, including, most crucially, a strong sense of social solidarity in the US. ‘Solidarity’ would mean that individuals in the US legitimately and properly can depend on each other for helping to secure the basic circumstances of healthy lives, no less than they depend legitimately on each other to secure the nation’s defense. If that were the moral imperative, government—the primary expression of shared responsibility—would defend and improve health just as energetically as it defends territorial integrity.”

Reverend Heber Brown is a living call-to-action for the Moral Determinants of Health, delivering and scaling food security for his local community and others in his growing garden of solidarity for health.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful.

I'm in amazing company here with other #digitalhealth innovators, thinkers and doers. Thank you to Cristian Cortez Fernandez and Zallud for this recognition; I'm grateful. Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.

Jane was named as a member of the AHIP 2024 Advisory Board, joining some valued colleagues to prepare for the challenges and opportunities facing health plans, systems, and other industry stakeholders.  Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.

Join Jane at AHIP's annual meeting in Las Vegas: I'll be speaking, moderating a panel, and providing thought leadership on health consumers and bolstering equity, empowerment, and self-care.