Selecting the Right Policy Tool to Lower Costs

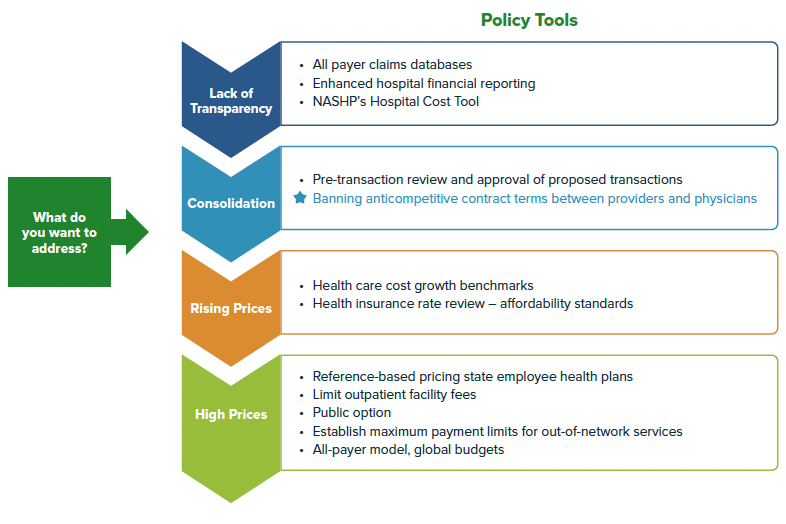

Efforts to make health care more affordable can target several problems that lead to high and rising hospital costs. Hospital and physician costs make up the majority of medical expenditures in the U.S. and rising hospital prices directly contribute to higher insurance premiums and make care less affordable for consumers. As seen below, identifying the right policy tool requires first identifying which “cost driver” should be addressed – this could be the lack of transparency in costs and pricing or the unchecked growth in hospital prices. As these issues are interwoven, these different policy tools complement one another and can be used together to combat the many contributors to high costs.

One of these contributors, hospital consolidation, has played an outsized role in making health care less affordable for consumers and employers. Evidence suggests that consolidation leads to higher hospital and provider prices and higher total expenditures – all while having little to no impact on improving quality of care for patients, reducing utilization, or improving efficiency. In many states, hospital markets are already consolidated so it’s not enough to try to prevent consolidation from occurring through pre-transaction review. The National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP)’s Model Act to Address Anticompetitive Terms in Health Insurance Contracts is one policy tool to target the negative impacts of consolidation and give states authority to limit already dominant health systems from abusing their market power. Essentially, by prohibiting anticompetitive contracting, a state will be helping payers, including employers on behalf of their employees, navigate a consolidated health system to achieve lower costs without affecting access to care.

Goals of Prohibiting Anticompetitive Contracting

Prohibiting anticompetitive contract terms will help level the playing field for negotiations between insurers and large health systems, allowing insurers to negotiate lower in-network prices and design networks with the highest quality, lowest cost providers. Without these prohibitions in place, health systems may leverage their “must-have” providers to restrict insurers’ ability to design high-value provider networks.

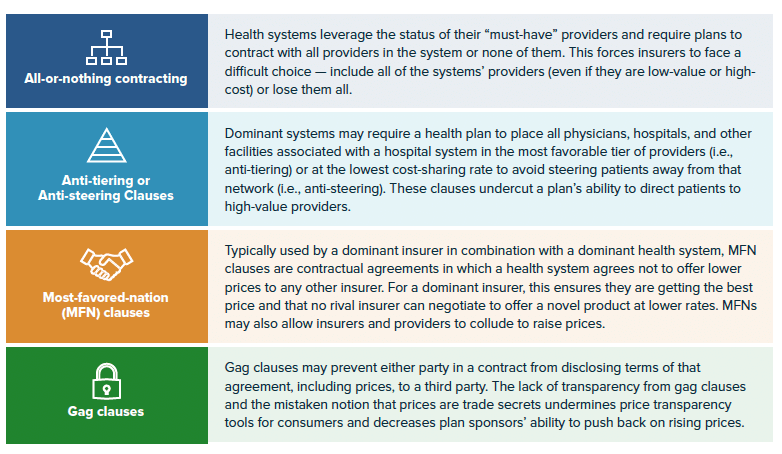

Due to existing requirements on insurers known as network adequacy, certain providers may be deemed a “must-have” or a facility or doctor that must be in-network for a health plan to meet existing requirements. Some providers may also be considered “must-haves” because of the providers’ reputation to entice employers and consumers to enroll their plans, an insurer must include those providers in-network. Knowing this, large consolidated systems can “tie” certain providers to “must-have” facilities, essentially demanding an insurer include other, often more expensive providers in-network. In some cases, health systems may demand all of their providers are in-network (all-or-nothing) or are included in the most preferred tiers (anti-tiering), meaning they are very accessible even if they are expensive. These various anticompetitive contracting terms mean that insurers and third-party administrators, often working on behalf of self-funded employers, are limited in their ability to negotiate lower prices or to develop innovative programs to improve quality or access.

NASHP’s model bill prohibits four types of anticompetitive contracting terms: all-or-nothing contracting, anti-tiering or anti-steering clauses, most favored-nations (MFN) clauses, and gag clauses. The chart below details how each contract clause may be used. The model also gives a state’s insurance commissioner or attorney general the ability to add other clauses through regulation that may result in anticompetitive effects. This flexibility is important as dominant health care entities’ contracting strategies may evolve to protect their market share and raise prices in response to these prohibitions.

As of June 2022, several states have introduced NASHP’s model, and several others had already prohibited some of these anticompetitive contracting terms. In 2021, Nevada enacted a law to prohibit all-or-nothing contracting, joining Massachusetts which has prohibited these clauses in limited or tiered-network plans for more than a decade. Nevada and Massachusetts also restrict the use of anti-tiering or anti-steering clauses. Seven states have banned gag clauses and 19 states have restricted the use of most-favored-nation clauses, although the language varies by state.

Understanding Impact: Examples from New York and California

New York

Most recently, in 2022, New York enacted the Health Equity and Affordability (HEAL) Act, which prohibits the use of most-favored-nation clauses and gag clauses. The New York law was supported by the 32BJ Health Fund, the organization that provides health insurance for members of Local 32BJ, the New York City branch of Service Employees International Union (SEIU).

32BJ become involved in the push for the HEAL Act due to concerns around anticompetitive contracting with New York Presbyterian during the 2021 plan year. During contract negotiations, New York Presbyterian tried to use anticompetitive contracting terms to force the fund to end an innovative maternity program that delivers high-quality pre and post-natal care at specific partner hospitals. These hospitals agree to provide services for as low as $40 in total out-of-pocket costs for members. In addition, the proposed contract terms would have forced the fund to eliminate joint replacement and bariatric surgery programs it established to provide care for as low as a $0 copay for members. Additionally, the prices paid by the 32BJ Health Fund to New York-Presbyterian are more than three and a half times, or roughly 358%, the price that Medicare pays for the same care at the same hospitals.

As a result, 32BJ severed ties with New York Presbyterian altogether, choosing to design networks without the health care system rather than give into their contracting demands. In addition, this spurred the fund to work with the legislature on the HEAL Act. While excluding an entire health system was an option for 32BJ, many self-insured employers that are smaller or in areas with fewer competitor hospitals would not be able to use this same strategy.

California

Impact of Anticompetitive Contracting in Northern CA

- 70% higher inpatient prices

- 15-55% higher outpatient prices depending on specialty

- 35% higher insurance premiums

- $575 million in damages per settlement

Further, Sutter demanded anti-tiering and anti-steering provisions which meant insurers could not guide members to lower-cost facilities that were also in-network. Sutter also included gag clauses in its contracts which meant that the employers that were responsible for paying for employees’ covered services could not request the estimated price of services before being billed.

As a result of these anticompetitive contract terms and Sutter’s market dominance, researchers at the University of California found that inpatient prices were 70% higher, outpatient prices that were 17 – 55% higher, and insurance premiums for Affordable Care Act (ACA) plans were 35% higher in Northern California than Southern California. Even after adjusting for possible wage differences between Northern and Southern California, procedure prices were 20 – 30% higher in Sutter-dominated Northern California. Therefore, Sutter’s dominance allowed the system to charge high prices, which directly affects consumer’s access to affordable care and coverage.

In the state case (UEBT v. Sutter), Sutter settled with the California Attorney General’s office rather than go to trial. The health system agreed to pay $575 million in damages and the settlement terms prohibit the system from enforcing any of these anticompetitive contract terms in future agreements. While the California Attorney General was able to hold Sutter accountable for these terms, it took a number of years and vast resources to do so. In the federal case (Sidibe v. Sutter), a jury trial took place in February 2022 and after almost ten years of litigation, the jury found that Sutter did not engage in anticompetitive conduct. While the plaintiffs are likely to appeal the decision, the case could send a message to other health care systems that these anticompetitive contracting practices are difficult to prove in court.

Although state attorneys general may be able to prosecute anticompetitive behavior, legal action is costly and challenging to pursue. Relying on state or federal antitrust enforcement is not a sustainable solution. As Emilio Varanini, deputy attorney general in the antitrust section of the California Department of Justice, has argued, “while litigation can blaze the way for addressing such anticompetitive conduct, ultimately legislation may be a far more effective tool for carrying out competition as a policy goal.”

Federal Overlap, Policy Limitations, and Complementary Tools

Federal Overlap and Importance of State Action

The federal Consolidated Appropriations Act (CAA), passed in 2020, prohibits insurers and group health plans from entering into agreements that include a “gag clause” or restrict insurers from making price or quality information available to patients. Compliance with the federal ban on gag clauses will be enforced through an annual attestation by insurers and group health plans. While the federal law offers an important backstop, several federal policies aimed at transparency have seen lackluster compliance. Creating additional state oversight through this law is important to hold insurers and providers accountable. Further, NASHP’s model allows individuals impacted by anticompetitive behavior to sue under a state’s unfair and deceptive acts and practices (UDAP) laws and to recover damages caused by these contract clauses. Various other federal proposals have considered prohibiting anticompetitive contracting terms, such as Sen. Klobuchar’s Competition and Antitrust Law Enforcement Reform Act of 2021, but it did not move past introduction. States can’t wait for the federal government to protect consumers.Other Policy Tools to Hold Insurers Accountable

- Network adequacy requirements

- Medical-Loss-Ratio (MLR) requirements

- Stronger premium rate review through Affordability Standards

- Requiring greater transparency and notification on provider networks

Policy Limitations and Complementary Tools

Common questions that state legislators raise regarding the anticompetitive prohibitions: Will this policy give too much power to insurers? Will prohibiting anticompetitive contracting give health plans the authority to create “skinny” networks or leave consumers without adequate access to providers? Since the business practices of many insurers are well regulated on the federal and state level, this policy aims to create more equitable standards for negotiating hospital prices that will impact overall health care costs for employers, employees, and consumers generally. Insurers are already required to meet certain network adequacy requirements which detail which types of providers (both in number and geographic location) a plan must contract with to ensure enrollees have sufficient choice and access. Network adequacy requirements contribute to the dynamic that allows health systems to leverage certain providers to force insurers to contract with less desirable providers. However, they’re also an important backstop to ensure appropriate consumer access, as long as state insurance commissioners have adequate authority and resources to enforce the requirements. States may also consider strengthening or updating network adequacy requirements to most effectively protect consumers.

Additionally, insurers are subject to certain requirements under the Affordable Care Act (ACA) to have their plans and premium rates reviewed annually. While rate review was ongoing on the state-level before the Affordable Care Act (ACA) was enacted, the ACA created a floor for review of “unreasonable” increases or a 10 percent increase in the individual or small-group market. The ACA also added in the medical loss ratio (MLR) requirement, which limits the amount of premium dollars that insurers can spend on administration, marketing, and profits. The ACA requires most individual and small-group market insurers to spend 80 percent of premium income on health care claims and limits other expenses to the remaining 20 percent of premium income. The effectiveness of these provisions at overseeing insurer behavior may depend on an insurance departments’ authority, resources, and ability to enforce these requirements.

Limiting anticompetitive behavior and contracting can reduce powerful, consolidated health systems’ market power, but it cannot unroll it. Efforts to reduce anticompetitive behavior could be coupled with policies that limit hospital prices or contain price growth. Additionally, states could consider policies like a public option that would increase insurer competition while also creating a more level playing field for contract negotiations. NASHP has other model legislation including on using insurance rate review to control costs, increase hospital financial transparency, prohibit unwarranted facility fees, and increase oversight of proposed health care mergers.

Acknowledgments

This brief was coauthored by Katherine L. Gudiksen, PhD, MS, The Source for Healthcare Price and Competition and Erin Fuse Brown, JD, MPH, Center for Law, Health & Society at Georgia State University College of Law.

This policy brief and the accompanying model legislation were produced with support from Arnold Ventures.