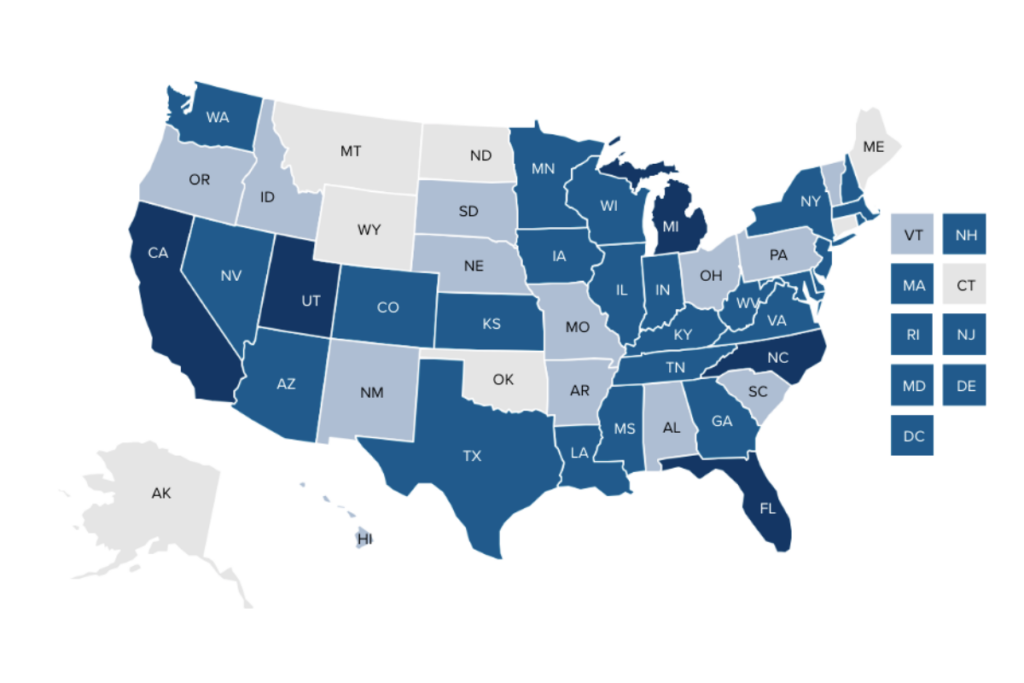

Almost half of the over 14 million children and youth with special health care needs (CYSHCN) in the U.S. are covered by Medicaid, and all of them have health care needs beyond that required by children, generally. In the past, states typically served children and adults with disabilities in Medicaid fee-for-service arrangements, but that trend has changed significantly in the last decade. In 2023, 48 states and Washington, DC enrolled children into Medicaid managed care programs. All but one of those states enroll at least some CYSHCN, along with other children, into managed care entities (MCEs) that also serve adults — most of these have done so since at least 2017. Forty states enroll at least some CYSHCN into comprehensive risk-based managed care organizations (MCOs).

Given that the trend for states to serve CYSHCN in MCOs continues, it is important to know how states structure their health care delivery system for CYSHCN. In early 2023, the National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP) analyzed the state Medicaid waivers, state plan amendments, and managed care contracts in all 50 states and Washington, DC to identify key provisions for CYSHCN. (The full results of the analysis are provided in this map and chart.)

A Few States Enroll CYSHCN into MCEs that Serve Only Children

Although almost all states enroll CYSHCN into the same MCEs that serve other children and adults, a few have also established specialized MCEs that serve only certain groups of children. This approach can help ensure that the unique health care needs of the group are met by enabling states to establish contractor performance standards targeted to meet the needs of the children the MCE will serve and by contracting with MCEs with specialized expertise and, often, experience. Eight states enroll various groups of children, including those CYSHCN who are members of the group, into such specialized MCEs.

- Tennessee, Texas, and Washington, DC enroll some or all children who qualify for Medicaid due to disability into specialized MCEs.

- Georgia and Kentucky enroll children involved with the juvenile justice system, along with those in foster care and/or receiving adoption assistance, into specialized MCEs. (A separate analysis conducted in early 2022 identified an additional eight MCEs serving only children in foster care.)

- Wisconsin and Wyoming enroll children with complex behavioral health needs into specialized MCEs that have responsibility for the delivery of both primary and behavioral health care.

- Florida enrolls CYSHCN who qualify for the state’s Title V CYSHCN program into a specialized MCE.

Some States Have Special Managed Care Enrollment Policies for CYSHCN

Many of the states that require children and adults to enroll into managed care allow various subgroups of these beneficiaries, such as those participating in a home- and community-based services waiver, to choose whether they will enroll in a managed care program or receive Medicaid services through another delivery system. That other delivery system is either fee-for-service or a different managed care program. Other states exclude some subgroups of beneficiaries from enrollment in a managed care program, choosing instead to serve these Medicaid beneficiaries through another delivery system.

Among the 48 states and Washington, DC, 14 have specialized enrollment policies for CYSHCN who are “receiving services through a family-centered, community-based, coordinated care system that receives grant funds under section 501(a)(1)(D) of Title V” (the state’s Title V Maternal and Child Health Services Block Grant program). Eight of these 14 states allow children receiving services from the state’s Title V CYSHCN program to choose whether they will enroll in the managed care program or receive Medicaid services through a different delivery system. The other six states exclude members of this group from managed care enrollment; they receive Medicaid services through another delivery system.

Most States Define CYSHCN in Their MCE Contracts

Clarity about which children are considered CYSHCN can enable states to measure (or require MCEs to measure) the care provided and can help ensure that measures will be comparable across MCEs and over time. It can also help clarify who gets served and help identify which MCE members may receive other specialized services the state establishes for CYSHCN. Over half of states with MCEs (26 of the 49 enrolling CYSHCN into MCEs) include a definition of CYSHCN in their contracts. Of the states that define CYSHCN, most (15 states) used the same, or a close variation of, as the federal Maternal and Child Health Bureau of the Heath Resources and Services Administration’s definition of CYSHCN. Nine states did not define CYSHCN specifically but did define individuals or members with special health care needs more broadly.

Most States Establish Quality Requirements in Their MCE Contracts for Members with Special Health Care Needs

All states with MCEs have a minimal level of quality provisions for all enrollees in their contracts. However, few states have established CYSHCN-specific provisions, in addition to the minimum quality requirements under Medicaid managed care required by federal statute. States with contract language specific to CYSHCN quality provisions may be more likely to include services and care that meet the unique needs of CYSHCN, which often greatly differ from the level of care needed by other children and adult populations served by the same MCE. Most states (31) have contracts that include language regarding quality provisions that are broadly inclusive of individuals or members with special health care needs. Ten states specifically include contract language regarding quality provisions for CYSHCN. For example, California’s MCO contract stipulates, “Contractor shall implement and maintain a program for children with special health care needs (CSHCN) which includes, but is not limited to, the following …

- Methods for ensuring and monitoring timely access to pediatric specialists, sub-specialists, ancillary therapists, and specialized equipment and supplies

- Methods for monitoring and improving the quality and appropriateness of care for children with special health care needs …”

Many States Require MCEs to Partner with the State Title V CYSHCN Program

Many states include contract provisions requiring that MCEs partner with state Title V Maternal and Child Health Block Grant programs, a federal program that plays a critical role in assuring comprehensive, coordinated systems of care for CYSHCN. Federal Title V statute requires that 30 percent of all state Title V Block Grant funds be used specifically for services for CYSHCN. In 2020, Title V programs supported 50 percent of all CYSHCN nationwide. Both Title V and Medicaid provide significant support for CYSHCN, and there are federal statutory requirements for Title V and Medicaid coordination. Eighteen states have contracts that include language describing some level of partnership requirement between the MCE and the state Title V agency or program. For example, West Virginia’s MCO contract includes the following provision:

“Bureau of Medical Services (BMS); the Bureau for Public Health’s Office of Maternal, Child and Family Health (OMCFH); and the MCO will establish a Memorandum of Understanding to implement coordination strategies to better serve children under the age of twenty-one, including those individuals with special health care needs, who are eligible for Medicaid managed care services. The MCO must collaborate with OMCFH care coordinators to share plans of care for children with special health care needs. The MCO must ensure that they do not duplicate services provided by OMCFH.”

Most States Include Special Contract Provisions as They Continue to Enroll CYSHCN in MCEs

States serving CYSHCN in Medicaid managed care is a trend that is clearly here to stay. Most states continue to enroll CYSHCN into the same MCEs that serve other children and adults. Inclusion of specific provisions for CYSHCN in contract language — such as definitions, quality provisions, and Title V partnerships — can help ensure certain services for CYSHCN are being provided. Five states (California, Florida, Michigan, North Carolina, and Utah) have MCE contracts that include language incorporating each of these provisions. Some states have more provisions than others, and most have established at least one provision targeted to CYSHCN. NASHP will continue to track state approaches to serving CYSHCN in Medicaid managed care.

Acknowledgements

Several NASHP staff contributed to this blog through input, guidance, or draft review, including Karen VanLandeghem and Heather Smith. NASHP wishes to thank officials at the Health Resources and Services Administration, Maternal and Child Health Bureau, for their review.

This project is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under grant number UD3OA22891, National Organizations of State and Local Officials. This information or content and conclusions are those of the authors and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by, HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. government.