by Establishing a Prescription Drug Affordability Board

In 2017, the National Academy for State Health Policy (NASHP) released model legislation to enable states to address high drug costs by creating a Prescription Drug Affordability Board (PDAB). Since then, six states have enacted laws to establish PDABs, and PDAB bills continue to be introduced and considered in legislatures each session. NASHP provides technical assistance and policy support to legislators and executive agencies interested in PDABs, and regularly convenes the six states that have established PDABs to share experiences and lessons learned.

State policy makers and NASHP have learned a lot since NASHP released the first model, and this new model PDAB bill reflects the best practices and experiences from the six PDAB states. It also incorporates experience from states that have implemented transparency laws. The new NASHP PDAB model legislation includes improvements such as:

- Mandating data reporting by health plans to provide the PDAB with actionable, state-specific data;

- Aligning health plan reporting with federal law to minimize reporting burden;

- Clearly defining and simplifying the information required to identify potential drugs for affordability review;

- Focusing on health equity concerns and the impact on underserved populations; and

- Specifying mechanisms to fund the Boards operations.

What is a PDAB and what is its purpose?

A PDAB is an independent board charged with assessing which prescription drugs present affordability challenges to a states health care system and to consumers of prescription drugs. Drug costs are high and continue to rise each year. This drives up the cost of insurance and causes consumers to pay more in out-of-pocket costs and premiums. A complex supply chain, opaque pricing practices involving rebate agreements, and general economic inefficiencies each contribute to the rising cost of prescription drugs. A PDAB is designed to identify unaffordable drugs, help assess the causes of high prices for particular drugs, and to identify appropriate policy solutions. Importantly, the NASHP model bill gives a PDAB the ability to set an upper payment limit for specific drugs within a state when it determines that a drug is unaffordable.

What are the primary tasks of a PDAB?

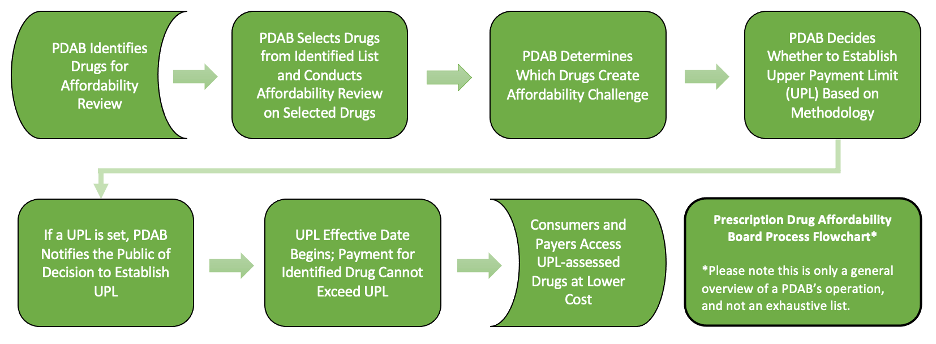

The primary tasks of a PDAB are 1) identification of high-cost drugs; 2) a determination, based on defined criteria and data analysis, whether an identified drug presents an affordability challenge; and 3) when deemed necessary, the establishment of an upper payment limit. The workflow is summarized in the following chart:

How is a PDAB structured?

The model legislation provides that a PDAB consist of five members, appointed by the states governor and confirmed by the state senate. The Board will operate as an independent unit of state government. The Board shall include members with expertise in health policy, health care economics, or clinical medicine. The Board also has the ability to contract with a qualified third party for additional support.

How is a PDAB funded?

The PDAB is funded through an annual assessment paid by stakeholders in the prescription drug supply chain, including prescription drug manufacturers, health plans and carriers, pharmacy benefit managers, and prescription drug wholesale distributors that sell or offer to sell prescription drug products to persons in the state. Funds are deposited in the Prescription Drug Affordability Fund, a non-lapsing account that provides the PDABs funding source. The Board can also receive grants or direct appropriations. The model legislation provides that the state legislature make an initial appropriation to fund the Boards start-up costs and operations.

How does the PDAB select drugs for review?

Because there are so many high-priced prescription drugs currently on the market, the model bill provides guidance to the Board with respect to selecting drugs for affordability review. The model bill directs the PDAB to consider drugs (including biologics) that meet certain price thresholds (or price increase thresholds). It also requires commercial insurance carriers to provide annual reports to the Board listing the top 50 drugs in terms of overall expenditures, price increases, utilization, and consumer out of pocket costs. To minimize reporting burdens, NASHP aligned health plan reporting requirements with those that are included in the Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2021. Stakeholder advisory groups can also recommend drugs to the Board for review.

What data can support the Boards analytical work?

Those states that already operate an all payer claims database (APCD) (30 states as of June 30, 2021) or have access to similar data sources are well-positioned to implement a PDAB. Those states may use those assets to access state-specific claims data, such as granular views related to drug spend and utilization. The model bill also directs the Board to consider publicly available pricing data or information acquired through a data-sharing agreement with another state. Manufacturers with drugs under review are invited to submit information to the Board, and the Board should also consider publicly available international pricing information.

What does it mean for a PDAB to set an upper payment limit?

An upper payment limit is the maximum reimbursement rate above which purchasers throughout the state may not pay for prescription drug products. An upper payment limit does not set the price that a manufacturer can charge, but does create a ceiling on what a payer can pay for a drug. For high-priced drugs affected by upper payment limits, rebates should no longer be necessary.

How many prescription drugs should a PDAB review and/or set upper payment limits for in a calendar year?

The model legislation does not prescribe the number of upper payment limits a PDAB may set in a given year. However, some states that created PDABs have imposed limits. For example, the Washington and Colorado enabling legislation caps the number of upper payment limits its PDAB may set to twelve each year. Marylands legislation does not include a limit on the number of reviews or upper payment limits its Board may set. Savings analyses conducted by NASHP indicate that a relatively small number of drugs drive a great deal of spending, and the data required by health plans on prescription drug spending will help PDABs focus on those drugs to maximize savings through upper payment limits.

What additional support is available to states interested in PDABs?

NASHP understands that states have limited budgets for staff, purchasing large datasets, and/or hiring contractors to assist in PDABs work to conduct drug affordability reviews and establish upper payment limit processes. States need access to centralized resources, including educational materials, data sources and analyses, and consulting expertise. In order to ensure that states enacting PDABs have the resources they need, NASHP will contract with a partner who has the background and expertise to provide technical assistance to PDABs.

Is there legal precedent for a PDAB?

Determining maximum payment levels for health care and other public goods is a state practice that has existed for decades. States regulate insurers and other public goods and services in markets with little or no competition. A PDAB builds on these various regulatory precedents, but for prescription drugs that create affordability challenges.

Unlike the 2017 anti-price gouging bill that was struck down in the Fourth Circuit, a PDAB wouldnt encounter the same legal challenges if it defines its jurisdiction over only drugs sold in the state.

Will states that implement PDABs face legal challenges?

PDAB legislation has been enacted in six states, and to date no state has faced a formal legal challenge. During the legislative process, however, manufacturers and business interests have strongly opposed the creation of PDABs, arguing that rate-setting in the form of upper payment limits is not permitted under the Dormant Commerce Clause and federal patent law. As it has with other model bills, NASHP has designed its model PDAB bill to withstand these anticipated legal challenges and is providing its underlying legal analysis to states interested in moving forward with PDABs.

Will upper payment limits hamper innovation and the development of new drugs?

Manufacturers routinely argue that efforts to reduce the cost of drugs will hurt new product research and development, and ultimately result in fewer innovative products coming to market. However, according to research from the USC-Brookings Schaeffer Initiative for Health Policy, empirical evidence suggests that the relationship between R&D spending and new drugs is modest. The new drug discovery pipeline has shifted away from large companies with sizable R&D budgets, and towards smaller companies driving innovation. Moreover, R&D spending at drug companies is primarily directed at extending patents for already profitable product lines rather than investments in the development of truly innovative new drugs.

What enforcement provisions are there for states that implement a PDAB?

Any manufacturer that attempts to withdraw a drug from a state because the PDAB has set an upper payment limit will be subject to a fine of $500,000, unless they provide notice of withdrawal at least six months in advance to the PDAB, the Insurance Commissioner, the Attorney General, and any entity in the state with which the manufacturer has a contract for the sale or distribution of the drug.

However, many factors make withdrawal unlikely:

- It would require major shifts in the supply chain to prevent drugs from reaching one state;

- The pharmaceutical industry already sells the same drug at many price points to different payers and in different distribution channels in order to maximize sales; and

- Manufacturers will be hesitant to abandon a market to its competitors.

How does the model legislation integrate health equity considerations into its design?

Affordability challenges in the prescription drug market heighten existing health disparities and exacerbate inequitable outcomes across communities, such as race, ethnicity, gender, disability status, or geographic location. People with disabilities, for example, are particularly affected by rising prices of prescription drugs. Many in this community may live on a fixed income, but still must deal with rising costs, increased out-of-pocket expenses, and rising deductibles. Historically disadvantaged communities are disproportionately impacted by chronic illnesses and certain health conditions, such as diabetes, HIV/AIDs, hepatitis B and C, hypertension, cardiovascular diseases, obesity, and asthma. Not only are they more likely to suffer from chronic illness, but they are also more likely to be uninsured and are therefore disproportionately hit hardest by ongoing rises in the list prices for prescription drugs.

The revised model legislation provides a new tool for states to help rein in disparate health outcomes and promote equity for their residents. First, by slowing the rising cost of prescription drugs, a state could provide meaningful relief to those communities that most acutely feel the pain of unaffordable prescription drugs. PDABs would also be required to consider whether the cost of a drug contributes to inequities to underserved communities when performing an affordability review, and to incorporate how an upper payment limit may prevent or alleviate health disparities across communities.

State officials who are interested in the Prescription Drug Affordability Board model legislation can contact Jennifer Reckwith questions or needs for technical assistance at jreck@nashp.org.