States are taking steps to provide additional prevention, treatment, and recovery services to higher-risk individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD), including those in contact with the criminal legal system. These individuals often require specialty services, intensive care coordination, and other interventions that go beyond traditional OUD services. These resources detail some of the strategies states are employing to move these individuals into treatment as rapidly and effectively as possible and avoid costly incarceration using the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM) developed by the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

States are taking steps to provide additional prevention, treatment, and recovery services to higher-risk individuals with opioid use disorder (OUD), including those in contact with the criminal legal system. These individuals often require specialty services, intensive care coordination, and other interventions that go beyond traditional OUD services. These resources detail some of the strategies states are employing to move these individuals into treatment as rapidly and effectively as possible and avoid costly incarceration using the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM) developed by the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration.

Individuals who are incarcerated have a disproportionately high rate of substance use disorder (SUD), as evidence suggests about 58 percent of local jail and 65 percent of state prison inmates meet diagnostic criteria for SUD. As the opioid epidemic continues, it poses significant challenges to corrections systems that are not designed nor resourced to provide the intensive medical and psycho-social treatment necessary to address opioid use disorder (OUD) and other SUD.

Continuing to arrest and incarcerate individuals with OUD also potentially exacerbates inequitable systems in which Black Americans are imprisoned at over five-times the rate of their White counterparts, despite their lower rates of illicit drug use. Arresting and incarcerating people with OUD creates forced abstinence from substance use, but it simultaneously increases the risk of overdose death following release because of the resulting reduction in tolerance. State prisoners serve an average of 2.6 years under state custody, a period of abstinence that does not negate the chronic, relapsing nature of SUD, but instead increases the risk of death from it. Former prison inmates have been shown to be 8.3-times more likely than the general population to die from an opioid overdose. Within the first two weeks after release, that risk is 40-times higher than in the general population. Abstinence reduces tolerance to opioids, but it does not reduce their effects, nor does it treat SUD. Re-entry from incarceration is, therefore, a risk factor for overdose death rather than a protective factor.

Fatalities on the rise:

Recent provisional overdose fatality data from the Centers for Disease Control (CDC) highlights the urgent need for states to expand access and explore no-wrong-door approaches to treatment, as overdose deaths continue to increase nationwide, peaking again in 2020.

Recognizing these challenges, states are developing policies to divert individuals with OUD into treatment rather than incarceration. States are:

- Embedding treatment services into corrections settings – an emerging practice that is costly to states in the absence of Medicaid reimbursement for incarcerated populations, and

- Diverting individuals to treatment by leveraging any OUD-related interaction – from crisis intervention to court programs and re-entry – as an opportunity to provide prevention and treatment services.

This approach requires significant coordination among policymakers from across state systems – behavioral health, Medicaid, courts, and corrections – to share resources, align policies, and develop clear protocols for programming. These coordinated state efforts, often formalized in governor’s task forces, cross-agency workgroups, and legislative commissions, are predicated on an ideological shift away from solely punitive responses and toward integrating treatment into the criminal legal system. This emerging policy perspective suggests that engagement with the corrections system for someone who has overdosed and/or is in possession of substances can result in arrest, incarceration, and subsequent withdrawal – or it can result in a potentially life-saving connection to treatment.

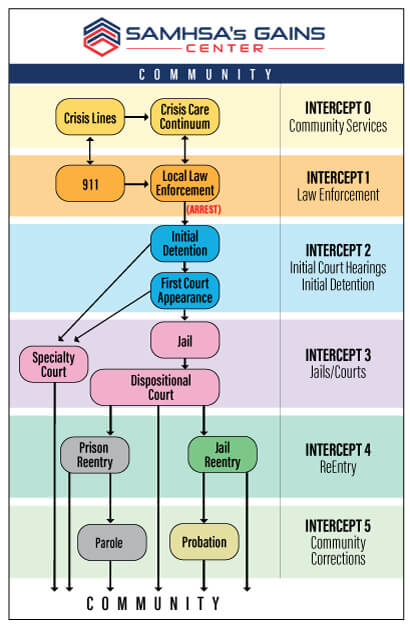

Viewing these approaches through the lens of the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM), originally developed by the US Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) as a conceptual framework for community-based interventions for individuals with mental illness, can help state policymakers identify opportunities for cross-agency interventions.

The SIM is most effective when used to assess available resources, determine gaps in services, and plan for community change from multiple systems, including mental health, substance use, law enforcement, pretrial services, courts, jails, community corrections, housing, health, social services, people with lived experiences, family members, and many others. States can use SIM to understand how people with mental and substance use disorders flow through the criminal justice system along six distinct intercept points:

- Community services

- Law enforcement

- Initial detention and initial court hearings

- Jails and courts

- Re-entry, and

- Community corrections programs.

At each intercept point, the stakeholders identify gaps, resources, and opportunities for adults with mental and substance use disorders and develop recommendations to improve system and service-level responses for adults with mental and substance use disorders.

This toolkit, informed by interviews with key leaders across several states, examines state policy actions at each of the intercept levels defined in the SIM framework, and explores opportunities for states to successfully integrate treatment and prevention services across the behavioral health and criminal justice continuum.

Across states, drug violations have led to most arrests in recent years. At the same time, hospital emergency departments have experienced a 37.2 percent increase in non-fatal overdose visits for all drugs, accelerated by the opioid epidemic. Creating effective and rapid-response community-based crisis intervention services can deflect individuals from the criminal legal system and reduce costly emergency department usage.

Additionally, arrest and incarceration rates reinforce racial inequities reflected in overdose rates – middle-aged Black Americans, in particular, have experienced disproportionate increases in fatal overdoses with rates doubling between 2015 and 2017.

Recent research shows that overdose calls to police are a predictor of possession arrests of Black individuals in low-income, urban areas. These coinciding trends highlight the cross-system impact of the opioid overdose epidemic. Crisis intervention services in community settings can help states:

- Address these kinds of inequities and prevent criminal legal system interactions for all people with opioid use disorder (OUD), and

- Reduce reliance on costly hospital emergency department care by connecting individuals to immediate resources and treatment.

Emerging best practice guidelines from the federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Agency (SAMHSA) identify community-based resources, such as crisis lines, mobile crisis teams, and dedicated crisis facilities, as services that can help to stabilize individuals with acute behavioral health needs and connect them to treatment. For individuals with OUD, the connection to treatment is a particularly important component. States are developing policies and programs, often in partnership with local leaders, to respond to overdose events and OUD-related crises by prioritizing behavioral health interventions and minimizing or removing the threat of arrest altogether.

Develop crisis lines for immediate connection to treatment. Crisis warmlines and hotlines present opportunities to prevent a crisis event altogether. In partnership with the Rhode Island Department of Health, emergency medicine physicians and addiction specialists at Alpert Medical School of Brown University in Rhode Island established a 24 hour-a-day, 7-day-a week buprenorphine induction hotline in response to both surging overdoses and lower utilization of emergency departments during the COVID-19 pandemic. The hotline, supported by both a federal Overdose to Action grant as well as the state’s CARES Act behavioral health funding, takes advantage of SAMHSA’s modified regulations during the public health emergency, providing immediate access to tele-induction of buprenorphine and linkage to continued outpatient treatment.

Integrate peers into crisis response teams. Instead of an arrest following the immediate life-saving intervention of first responders, overdose response programs provide a connection to services designed to prevent the next overdose and offer treatment resources. States are developing practices that dedicate a team of co-responders to provide post-overdose support, including peers with lived experience, to better meet the needs of individuals experiencing an overdose crisis. Engagement with peers as part of care teams, an emerging practice that utilizes the unique experiences of people in recovery from SUD, is associated with reduced substance use and better treatment retention. North Carolina made this kind of team response to overdoses a priority in its Opioid Action Plan. In order to support localities as they develop these Post-Overdose Response Teams (PORT), the state’s Office of Emergency Medical Services partnered with the Division of Public Health to provide in-person regional trainings on team composition and creation. The state followed these trainings with the publication of a PORT Toolkit that defines the major components of successful program implementation, placing significant emphasis on ensuring that a peer is both consulted in program development and included on active teams. The state’s toolkit includes directives for localities on developing community assessments, community-led program design, referral protocols, and data collection for program evaluation. Toolkit guidance also stresses that North Carolina’s Local Management Entity-Managed Care Organizations (LME-MCO) are important PORT support network partners. While the outreach and referral services provided by the PORTs are not Medicaid-reimbursable, many medical, treatment, and other behavioral health services provided by the LME-MCO providers under the state’s 1915(b) waiver are covered.

Rhode Island hospital licensure regulations for SUD, OUD, and chronic addiction discharge planning (216-RICR-40-10-4.6.1(D) et seq.):

Peer recovery: The hospital shall offer all patients the opportunity to speak with a peer recovery support specialist, if those patients are diagnosed with SUD or OUD using the evaluation protocol required by section 4.6.1(D)(1) of these regulations, or are treated for an opioid overdose.

Treatment services: The hospital shall provide information to patients about appropriate inpatient and outpatient services, including but not limited to medication-assisted treatment and biopsychosocial treatment, if those patients are diagnosed with SUD or OUD using the evaluation protocol required by section 4.6.1(D)(1) of these regulations, or are treated for an opioid overdose. Hospitals must make a good faith effort to assist the patient in obtaining an appointment with a qualified licensed professional.

Rhode Island also implemented procedures that maximize an emergency department interaction when individuals are transported to a hospital following an overdose by integrating peer services in overdose incidents. Directed by the legislature, the state’s health department promulgated regulations for comprehensive discharge planning, requiring that individuals who are diagnosed with an SUD or treated for an overdose be presented with information to support connections to treatment and recovery services. Hospitals must ensure that these patients are offered the opportunity to speak with a certified peer recovery specialist, and that they are given information about inpatient and outpatient treatment, including access to medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD). This peer intervention, called AnchorED, has not only led to ongoing engagement with treatment services after overdose, it has also helped the state to train and dispense naloxone to overdose survivors. A pilot for peer services through commercial insurance in Rhode Island through Blue Cross and Blue Shield resulted in higher engagement and adherence to treatment post-overdose and projected a 67 percent reduction in long-term health care costs for participants.

Establish non-hospital sites for crisis service delivery. In 2017, states experienced more than 800,000 opioid-related hospitalizations, and Medicaid was the most frequent payer for these services. Hospitalization is costly to states and not always medically necessary to stabilize an individual experiencing an overdose. To avoid hospital utilization when safe to do so, states are investing in dedicated sites for behavioral health crisis intervention. Alabama recently committed $18 million in state funds to pilot three Crisis Diversion Centers across the state, bolstering Gov. Kay Ivey’s and the Alabama legislature’s commitment to creating a crisis continuum of care. The pilot seeks to divert individuals experiencing an SUD or mental health crisis from hospitalization or arrest, by facilitating handoffs from law enforcement, first responders, and/or hospital staff. Those responding to crisis situations are able to transport individuals needing care directly to the crisis diversion centers. At a center, individuals can immediately access Medicaid-reimbursable stabilization services on-site, including medically monitored detox and MOUD prescriptions, and receive necessary treatment referrals. This approach provides law enforcement with an alternative to arrest and reduces reliance on hospitalization, while clinically addressing an individual’s care needs with urgency.

Working with stakeholders and policy leaders, Alabama developed comprehensive standards for the care environment, staffing, and protocols in these crisis centers, and released a Request for Proposals (RFP) that outlined requirements for care delivery in 2020. Notably, the RFP required the establishment of a community collaborative composed of mental health and SUD treatment providers, and hospital leaders alongside law enforcement, judges, and advocates. Alabama cites the state’s existing Stepping Up initiative, a jail and emergency department diversion program for people with mental illness and/or SUD that is operational in 21 of Alabama’s 67 counties, as instrumental to this crisis services continuum and the development of crisis centers. Stepping Up Alabama, implemented by the Alabama Department of Mental Health (ADMH) in 2018, relies on community behavioral health centers to provide crisis intervention. Support for 11 of these centers was provided through one-time $50,000 competitive grant awards, released over two years, by ADMH to set up both behavioral health service provision and wraparound supports for individuals in crisis. Community behavioral health centers used funds to incorporate intensive case management, mental health services that include court advocacy, social services to address social determinant needs, and the development of local planning committees and community outreach programs.

As part of initiatives to reduce emergency department utilization, New York integrated crisis services into multiple Medicaid reforms under a Medicaid Section 1115 demonstration waiver, creating an opportunity for behavioral health crisis service reimbursement through managed care. The New York Mobile Crisis Services approach relies entirely on behavioral health interventions, and while it requires close collaboration with law enforcement, licensed clinicians – alongside non-licensed support staff – lead mobile services, removing law enforcement from crisis events unless they are called in for co-response.

Through a pilot program with the Baltimore Department of Health, Maryland began operating a Crisis Stabilization Center with partners at Tuerk House in 2018 that offers round-the-clock access for both withdrawal management and connection to immediate treatment. Staffed by both nurses and peer recovery specialists, the center provides beds, showers, and meals to individuals in crisis, as well as medical evaluations, case management, and connections to buprenorphine induction and other MOUD treatment. In 2018, the state legislature mandated a Behavioral Health Crisis Response Grant Program for services statewide, establishing two years of general fund appropriations for localities to apply for funding to develop or expand integrated mental health and SUD intervention services designed to divert individuals from emergency departments.

Community Services and Prevention (Intercept 0) – Key Highlights

- Consider diversion from both emergency department care and incarceration as equal, interconnected goals.

- Develop partnerships with leaders from both hospitals and law enforcement to align program components and establish protocols.

- Include people with lived experience and advocates when building crisis intervention models. Crisis response teams delivering services and community coalitions that help to steer them benefit from the perspectives of individuals who have experienced OUD crisis and personally navigated systems.

- Develop crisis services facilities and infrastructure to ensure that individuals are efficiently stabilized and connected to treatment by behavioral health and SUD specialists.

Seek opportunities to optimize Medicaid reimbursement in those settings.

Additional Resources

- NASHP Webinar: Using Crisis Intervention and Prevention to Divert Individuals with OUD into Treatment and Supportive Services

Arrests are costly, leading to average court fees exceeding $13,000 per incarcerated individual and an estimated annual total of $65 billion expended nationwide across court systems. Additionally, arrests do not address the behavioral health needs that may drive criminal behavior. Treatment for opioid use disorder (OUD), on the other hand, has been shown to produce savings – every dollar spent on treatment generates an estimated criminal legal system savings of $4 to $7.

Law enforcement officers arrest people as a routine part of their jobs, and individuals who are arrested undergo a booking process to set bail and determine if, when, and under what conditions, they will be released. While this process may serve the immediate interests of public safety, arrests can be dangerous for people with OUD and can lead to unexpected detoxing and subsequent withdrawal in a custodial setting unequipped to provide necessary medical supervision. In the absence of careful monitoring by a medical professional, withdrawal can be risky and in some cases, life threatening. Pregnant women with OUD who are arrested, incarcerated, and forced to withdraw without immediate medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) are at high risk of miscarriage and other serious complications. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) recommends against opioid withdrawal during pregnancy.

Encounters with police can be deadly even if they do not result in unexpected detox. One in every 1,000 Black men is killed by the police, and Black women, Indigenous Peoples, and Latinx men are killed by police at rates higher than White people.

In order to avoid the arrest process altogether, states are building programs in which law enforcement officers and first responders are co-leading interventions with behavioral health partners that, instead of arrest, connect individuals to case management and treatment services.

Develop pre-arrest diversion programs. In Washington State, the King County Department of Community and Human Services and local law enforcement collaborated in 2011 to create the Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) model that has since been adopted by other states and localities, particularly for people with OUD. LEAD targets individuals involved in low-level drug and other crimes who have been arrested multiples times. To disrupt this drug use-arrest cycle, officers have discretion to connect these individuals to intensive case management instead of arrest and booking.

Case managers, who partner directly with local prosecutors on LEAD cases, are often provided through community behavioral health organizations. These staff are able to bill Medicaid for treatment and develop connections to other necessary services. LEAD participants and their communities benefit from this approach – participants demonstrate 60 percent lower recidivism rates than those with similar charges who did not participate. Given this success, Washington State is expanding the LEAD program, creating new sites and appropriating $4.8 million in general funds for their development. Washington municipalities can also leverage funding from local mental illness and drug dependency (MIDD) tax revenues that support LEAD and other SUD intervention and treatment programs.

Relying on cross-agency partnerships, West Virginia implemented LEAD in 17 counties, focusing solely on diverting individuals with OUD into treatment services. The West Virginia Department of Health and Human Resources (DHHR), along with the state’s Office of Drug Control Policy and DHHR’s Bureau for Behavioral Health, developed partnerships with five local Comprehensive Behavioral Health Centers, issuing funds from a federal Comprehensive Opioid Abuse Site-based Program (COAP) grant. Colorado similarly adopted the LEAD approach, allocating $2.3 million per statutory directive from marijuana sales to the state Office of Behavioral Health to support four local programs through behavioral health-law enforcement partnerships. Colorado specifies that law enforcement officers have the discretion to refer individuals whose repeated violations are “driven by unmet behavioral health needs.” The program offers trauma-informed intensive case managers who can connect individuals to a range of resources including treatment, housing, and vocational services.

“What we do all the time is create another task force to go after the supply side. What we don’t do very much, from the law enforcement standpoint, is deal with demand, which is really the individuals who are struggling with addiction … As opposed to putting all of our eggs in the supply basket of trying to disrupt the flow of narcotics coming into our communities, we can make great strides not only in saving people’s lives, but hopefully lowering crime rates.” –

Rhode Island State Police Captain .

Leverage law enforcement partners for outreach initiatives. The Rhode Island State Police (RISP) funds and coordinates the HOPE initiative in partnership with municipal police departments and local behavioral health providers. This statewide initiative was driven by the recognition among RISP agency leadership that targeting the supply of narcotics alone was not sufficient to address the high rate of overdoses and drug-related crime across the state. The initiative recruits local police officers to participate voluntarily while off-duty from patrol in their localities. The HOPE Initiative pairs officers with mental health clinicians to conduct outreach after police departments report an overdose. The team arrives in plainclothes and rides in unmarked vehicles to minimize the fear that can be associated with police visitation. The initiative, supported by the same federal COAP funding used for LEAD programs in West Virginia, pays officers overtime out of these funds in the RISP budget, so as to not rely on local police budgets. The program is structured as an opt-in model to ensure that officers participating are enthusiastic about the initiative and less likely to carry stigma about SUD.

Reflecting the trend across states to better train and engage law enforcement officers in crisis intervention, the Portland, Oregon, Police Bureau has dedicated a unit to behavioral health, which responds to behavioral health crises at four tiers of action depending on the severity of the crisis. The unit includes a Behavioral Health Response Team, composed of a police officer and a licensed mental health clinician, who conduct proactive follow-up with individuals and work to connect them to resources. The Service Coordination Team within this unit has the sole responsibility of coordinating with treatment and housing providers to connect individuals with services that address the underlying factors that contribute to criminalized behavior.

Transform police and fire departments into treatment access points. Massachusetts trailblazed the concept of arrest-free take-back stations that connect individuals to immediate treatment. In 2015, Gloucester’s chief of police committed to providing OUD treatment and not charging any person who presents at the police station, turns over any remaining drugs or paraphernalia, and asks for help. Named the ANGEL program, this approach pairs individuals with a volunteer “angel” – often a peer – who assists in connecting them to care. In its first year, Gloucester’s ANGEL program connected over 400 people to treatment. The program quickly spread to other police stations in Massachusetts and other states, propelled by the Police Assisted Addiction and Recovery Initiative (PAARI) that provides support to local police stations for these programs, some of which have seen decreases as high as 25 percent in drug-related crimes after implementation. Maryland’s Safe Stations programs, developed and funded under the Department of Behavioral Health’s Maryland Opioid Recovery Response (MORR) initiative, similarly designates certain fire and police departments as sites to turn in drug wares and request access to treatment. These sites provide immediate medical evaluation, peer recovery support, and transportation to appropriate treatment facilities. If an individual has an outstanding warrant, the Office of the State’s Attorney will review and recommend treatment if the warrant is for a nonviolent offense before the case proceeds.

Law Enforcement and Avoiding Arrests (Intercept 1) – Key Highlights

- Consider models that empower law enforcement to divert individuals with OUD into programs that support their connection to comprehensive treatment and services, encouraging a shift that considers low-level drug crimes the result of behavioral health needs rather than criminal activity.

- Use existing law enforcement crisis intervention training to develop partnerships and cross-systems outreach among behavioral health agencies, law enforcement, and providers.

- Utilize traditionally authoritative settings like police and fire stations to allow individuals to seek and be connected to treatment.

In addition to a decreased risk of re-conviction and re-arrest, pretrial diversion programs may deliver larger systems benefits – preserving judicial resources and reducing associated costs. A study of one county’s pretrial diversion programs calculated over $1 million in annual savings in court costs and legal fees, and more than $600,000 savings for prisons and jails. The initial booking, intake, and arraignment process upon arrest offers an opportunity to screen individuals for substance use disorder (SUD), and with the right policies in place, divert them from incarceration and into treatment and other pre-trial services.

Jail personnel and health screeners are presented with early opportunities to assess individuals and identify when additional evaluation is warranted. Pretrial service staff or clinicians then conduct more in-depth assessments in order to determine eligibility for pretrial diversion, an approach that offers a voluntary, community-based alternative to incarceration and the potential for the dismissal of criminal charges if the participant completes program requirements.

It should be noted that for all their successes, pretrial diversion opportunities have not always been applied equitably. Black defendants are less likely to be diverted at the pretrial stage than their White counterparts. They are, consequently, more likely to receive a criminal conviction and bear the consequences of having a criminal record. Resources such as the Institute of Justice’s Prosecutor’s Guide to Advancing Racial Equity can assist states in understanding and mitigating discriminatory impact on communities of color.

Here are steps for implementing pretrial diversions:

Screen individuals upon arrest. An initial screening for SUD is key to ensuring that individuals who need treatment can be identified early post-arrest, though intoxication and withdrawal can be challenging to screening processes. Several validated screening tools that can be used by both clinical and non-clinical staff are available to help determine if an individual has an SUD and requires further assessment:

- The Texas Christian University Drug Screen 5

- The Adult Substance Abuse Subtle Screening Inventory-4 (SASSI-4), and

- The Addiction Severity Index (ASI).

Establish cross-systems processes to determine appropriate levels of care. State behavioral health agencies and courts can partner to better shape treatment and behavioral health interventions necessary for an individual who has been arrested. Participants in Connecticut’s pretrial drug education and community service program (DECSP), operated by the state Department of Mental Health and Addiction Services (DMHAS), are referred into the program by the court after being charged with drug or drug paraphernalia possession. A clinical evaluation determines recommendations to the court, which ultimately decides the level of intervention and makes connections to contracted providers for individual and group psycho-social services. Additionally, for those assessed to have an immediate need for clinical treatment, Connecticut DMHAS administers a Jail Diversion Substance Abuse (JDSA) Program, connecting individuals directly to detox and/or inpatient residential programs on the day of arraignment. If, upon assessment, the court finds that an individual was under the influence of a substance at the time of an arrest, and that underlying SUD is a driver of the criminal behavior, a judge can place that individual in treatment as opposed to incarceration. The JDSA program includes additional coordination and supports for ongoing treatment and housing, and it facilitates reporting and monitoring with the court.

Collect and share data. The federal Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) has identified the effective use of drug court and treatment data as a key component of Intercept 2, recognizing that connecting corrections and court-related data within an individual’s records from behavioral health providers in the community can help to assess current treatment needs. To support these efforts, SAMHSA has published Data Collection Across the Sequential Intercept Model (SIM), a manual that addresses many of the steps needed to collect and use data to better understand and improve the outcomes of people with mental illness and/or SUD who come into contact with the criminal justice system. Sharing information across systems can also help states and localities understand how treatment resources are being used in drug court settings and how that treatment is impacting outcomes.

Virginia takes a locality-by-locality approach to data sharing in support of behavioral health and corrections data integration. In 2018, the state legislature directed the creation of a state chief data officer (CDO) position, requiring that the CDO focus initial attention on data issues related to SUD, with particular attention to OUD and overdose. The office of the CDO was able to leverage a 2017 partnership between the state’s Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services and the Department of Criminal Justice Services, the latter of which had received a federal Technology Innovation for Public Safety (TIPS) grant to build data infrastructure for a single-locality pilot. The initial pilot brought together de-identified data from community behavioral health centers, hospitals, forensics, law enforcement, and other community sources into one platform to visualize the data and analyze the interactions of these systems. With these data tools the pilot locality was able to identify:

- Patterns in substances associated with various types of arrests;

- Criminal charges that indicated a need for treatment; and

- Other trends in systems engagement among individuals who overdosed or were arrested.

The state used federal State Opioid Response (SOR) grant dollars to continue funding to expand the platform, now known as the Framework for Addiction Analysis and Community Transformation (FAACT). FAACT has expanded to include new regions of the state and officials anticipate continued growth statewide.

Oregon requires Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) to coordinate data with local jails to share the behavioral health diagnoses, medications, and support services accessed by members who are incarcerated. Per contract language, MCOs also agree to coordinate with jails and local law enforcement to strategize on ways to decrease engagement with law enforcement and mental health-related arrests, as well as reductions in admissions to and lengths of stay in jails.

Allow individuals to formally request treatment through court systems. Ohio’s approach to pre-trial diversion reflects an understanding that SUD is often a factor in criminal behavior. This is clearly borne out in a 2014 report from the Ohio Office of Criminal Justice Services that showed a 600 percent increase in the rate of opioid-related crime between 2004 and 2014. Per a recent amendment to the state’s long-standing intervention in lieu of conviction statute, prior to entering a guilty plea, an individual may request treatment in place of incarceration from the court, and that request must include a statement summarizing how substance use contributed to commission of the charged crime. Following an assessment from a community addiction services provider, who recommends treatment and intervention options, the court can grant the request and create an intervention plan that requires the defendant to refrain from illegal drug and alcohol use, engage in treatment and recovery services, and participate in regular screenings for at least one year, in addition to other conditions the court may impose. The same amendment also allows for sealing of certain felony conviction records a year after the conclusion of probation, making social supports like housing and employment less challenging to access. Notably, an earlier 2018 language amendment for the program added “promotion of effective rehabilitation” to stated purposes of the bill, emphasizing the behavioral health aspects of this approach while minimizing the punitive aspects.

Pretrial Diversions Reduce Costs and Improve Access to Treatment (Intercept 2) – Key Highlights

- Validated screenings and intake processes can help identify candidates who would benefit from SUD treatment. Given the very short period of time for attorneys to assess the needs of a client prior to arraignment, screenings can help to level-set and connect individuals to behavioral necessary services.

- Data collection and sharing across health care and corrections systems allows states to more efficiently identify individuals with SUD, connect them with their treatment records, manage their treatment needs, and refer them to appropriate treatment upon release.

- Leverage courts as access points to treatment by providing alternatives to sentencing coupled with behavioral health clinical assessments.

Jail-based treatment programs and drug courts use the criminal legal system infrastructure to offer intensive opioid use disorder (OUD) treatment to high-needs individuals who have been sentenced. These programs are designed and resourced by policymakers in order to retool traditional public safety settings to become access points for treatment. Jail-based treatment programs and drug courts both rely on administrative protocols to ensure coordinated operations, specially trained staff and leaders, and relationships with community clinical providers.

Although drug courts have proven effective in decreasing recidivism as compared to the traditional prosecutorial process, drug court participants who are Black are less likely to successfully complete drug court programs than their White counterparts. Because drug court programs generally require a guilty plea in order to participate, participants who do not graduate from the program may be sentenced immediately.

How Chesterfield County’s jail takes advantage of Virginia’s behavioral health policies

Individuals participating in the Helping Addicts Recovery Progressively (HARP) program in the Chesterfield County jail have access to a range of services and activities to support treatment and recovery. These include training through Virginia’s Department of Behavioral Health and Developmental Services’ (DBHDS) REVIVE! naloxone program and medication-assisted treatment provided by the jail’s in-house physician. Additionally, through an opportunity unique to program participants, the jail offers the state’s Peer Recovery Specialist (PRS) certification course for those interested in obtaining that credential. The 72 hours of didactic work required by DBHDS is provided by the jail, and a partnership with a local recovery community organization offers the required 25 hours of supervised practicum experience (of a total 500). Program participants are able to leave the jail with peer certification, which provides a connection to the recovery community and a pathway to employment as a certified PRS.

State support for jail-based treatment. While many states have implemented treatment for OUD in prisons, including evidence-based medications, implementation in jails is driven by localities. (View a NASHP chart detailing treatment options in state prisons here.) States are, however, able to support jail-based treatment, particularly through state budgets. Lawmakers in Colorado mandated that jails receiving Jail-Based Behavioral Health Services (JBBHS) funding must have specific policies in place to provide medications for OUD (MOUD) treatment, tying state funding to evidence-based interventions. Jail-based treatment provides evidence-based interventions, including MOUD, to individuals while they remain incarcerated in local and regional/county jails. These programs have been implemented in only about 5 percent of jails nationwide, though legal action is emerging that may compel growth. Jails are administered in most states by municipalities or counties, while states operate prisons through their departments of corrections. Neither incarceration setting can use Medicaid to fund treatment due to the “inmate exclusion” – federal statutory language that prohibits Medicaid payment of services for individuals who are inmates of public institutions.

Drug courts offer supervised programming for individuals for whom SUD is an underlying factor in criminal charges, but they do so while an individual lives in the community, though jail stays may be used for initial monitoring and sanctions. Supervised by judges and staffed by multidisciplinary teams of defense attorneys, prosecutors, community corrections officers, and behavioral health clinicians, these programs target low-level criminal defendants. Drug courts are designed to prevent both recidivism and return-to-use, relying on interventions and approaches to ensure that behavioral health treatment and courts systems are working strategically in support of treatment for participants.

Drug court teams frequently enter into agreements that define the roles and responsibilities of each team member as well as the goals of the team as a whole. For example, by signing New Hampshire’s Memorandum of Understanding (MOU), drug court team members commit to “collaborate in an effort to reduce substance abuse and drug-related criminal activity in their jurisdictions by supporting a comprehensive program of services to meet the needs of the drug court participants.” The MOU also explicitly defines the role and lists the duties of the drug court judge, coordinator, case manager, probation officer, prosecutor, defense attorney, treatment provider, and law enforcement officer, while leaving open the option for inclusion of additional team members from housing agencies, community corrections, etc. All team members also agree to preserve the confidentiality of information learned about drug court participants and must sign a non-disclosure agreement.

Establish standards for training and education of drug court judges and court officers. The Oregon drug court program is the second-oldest in the country and was initially developed to serve people charged with drug possession but recently its focus has shifted to high-need, high-risk individuals diagnosed with treatable substance use or mental health disorders and a high probability of re-offending if they go through the traditional criminal legal system. Until recently, the governing standards for drug courts were administered by the state’s Criminal Justice Commission, a small state agency that oversees criminal legal policy and research and assesses and administers grants to support specialty court programs. Previously, the commission has enforced standards based on those created by the National Association for Drug Court Professionals (NADCP). However, the chief justice of the state’s highest court recently created the Oregon Judicial Department’s (OJD) Behavioral Health Advisory Committee to advise her and the OJD on behavioral health issues that pertain to the work of the courts. Now, Oregon’s specialty court program and its staff will receive state-specific guidance, education, training, and peer review, among other quality improvement strategies. Specialty court standards will also be customized based on the type of each court, with different components for family treatment, mental health, etc.

Support drug court budgets with cross-systems resources. The collaborative nature of drug courts is reflected in how they are funded. In addition to state funding to support administrative programming costs, two federal agencies provide significant funding for drug courts, available to both states and localities – the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) provides drug court grants as does SAMHSA, whose grants are specific to growing collaborative approaches to the treatment components of the courts. The US Department of Justice also maintains a resource list for drug courts, which includes links to currently available federal funding sources. States also use State Opioid Response (SOR) funding to support treatment costs in drug courts. Minnesota dedicated SOR dollars to support several drug courts, including allocating more than $200,000 to a health system to serve as the MOUD provider for a local drug court. California is using SOR funds to support a learning collaborative that is expanding access to MOUD in drug courts and other criminal legal settings. In its Medicaid managed care contracts, Oregon includes language directing health plans to provide specialized SUD services specifically designed for justice-involved individuals and to ensure member access to appropriate SUD services, including drug courts.

“It is important to bring an understanding of the nature of SUD to the bench, explained an Oregon Drug Court Judge. SUD is not a legal excuse for criminal behavior, he acknowledged, but does present an opportunity to, “…help a person get well so that they never again commit a crime and never again find themselves in the criminal justice system. To me, it’s the difference between achieving a short-term public safety improvement by incapacitating this person, and achieving a durable, long-term solution to the public safety problem by holding the person accountable while giving them access to treatment.”

Leverage policy to support MOUD. Providing MOUD to participants can present a challenge for drug court leaders, as the diverted medications themselves can be a driver of drug-related charges. While most diverted buprenorphine is used in ways that are consistent with therapeutic purposes, judges may perceive prescribing that same kind of medication as counterintuitive – or even counterproductive. Despite the efficacy of MOUD and a resolution statement from NADCP in support of its use in drug courts, almost half of drug courts nationwide did not use MOUD in their programs as of 2012.

In order to incentivize use of MOUD, the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) requires that drug courts applying for funds make the medications available to participants and does not allow programs to discontinue treatment for individuals who were on it when entering a program. SAMHSA’s funding is designed to support MOUD in drug courts, and the agency published guidance to disseminate best practice approaches to providing it effectively. States are also incentivizing MOUD use through policy. Oregon did not allow MOUD in drug treatment court as recently as five years ago, but a 2020 state law now prevents specialty courts from denying participation in the program solely because the individual is taking MOUD. A similar law was approved in New York in 2016 with Missouri following suit in 2017 – both states prohibit use of MOUD as a reason to remove a participant from a drug court.

Drug court cost savings. As compared to individuals who go through the conventional criminal legal system, drug court participants experience lower rates of recidivism, which yields cost savings. Each dollar invested in a drug court yields $3.36 in averted criminal legal costs. Cost savings may be even greater if other indirect costs, such as health care, are considered.

Coordinate services and providers for evidence-based treatment quickly. New York’s pre-plea Opioid Treatment Courts (OTCs) were created as a way to prevent overdose deaths among individuals as they waited for a hearing in the state’s drug treatment courts. The state operates two models across 14 OTCs in the state, one originating in the Bronx and the other in Buffalo. In the Bronx court system’s OTC, staff redirects candidates to a treatment coordinator, who is in the courtroom at all times. The coordinator connects participants with a treatment program, which, if successfully completed, leads to dismissal of criminal charges. Under the Buffalo model, jail staff perform simple screenings on program candidates and explain how the OTCs work. If an individual decides to participate, jail staff connect with the court to suspend prosecution and the individual is given a clinical assessment by a state-certified treatment program to determine and provide treatment needs, including medication induction – through a mobile MOUD van parked outside the Buffalo courthouse – and treatment supports. The state uses SOR dollars to offer assessment and peer services to OTC participants, as well as treatment services through partnerships with local OTPs. After 90 days of treatment, an individual is either diverted to the drug treatment court or charges are dropped altogether. New York reports that preliminary findings from a recent study by NPC Research, funded by the BJA, show that New York’s first opioid court in Buffalo is succeeding in its primary goal of saving lives, as participants were half as likely to die of a drug overdose within one year.

Many of New York’s OTCs employ a SOR-funded certified peer and clinician, both of whom provide Medicaid-reimbursable services. Opioid treatment and rehabilitation services, including peer services, may be provided outside of the four walls of a facility and within the community, which includes criminal legal settings. While these courts are currently operational, the state’s recent passage of bail reform means that people can no longer be held on bail for most misdemeanors and nonviolent felonies. While the goal of the legislation was designed to mitigate poverty as a factor for people remaining in custody pending trial, it may have also decreased opportunities for OTCs to engage individuals who previously would have been detained overnight. New York state is actively exploring creative ways to more rapidly engage individuals who may have an SUD before they are released.

Jail-Based Treatment and Drug Courts (Intercept 3) – Key Highlights

- Develop training and standards for judges and other court staff that addresses OUD and evidence-based methods of treatment. When court employees work with clinicians, including community behavioral health staff, a shared perspective can help ensure that all team members are supporting best clinical practice.

- Provide MOUD to participants who have been clinically assessed to benefit from this type of intervention.

- Engage individuals who need treatment immediately in services by coordinating staff to identify and connect to providers.

The period immediately following release from an incarceration setting is a particularly vulnerable time for people with opioid use disorder (OUD). Re-entry to the community, especially during the first two weeks after release, presents a significantly increased risk of mortality from overdose due to decreased drug tolerance resulting from incarceration. The chronic nature of OUD, in addition to the stresses of re-entry and attendant challenges finding employment, securing housing, and reconnecting with family and social circles, can often trigger urges to use, particularly when OUD remains untreated.

Mortality risk upon re-entry is lower for individuals who have participated in evidence-based treatment that includes MOUD while incarcerated – especially those who have had access to all three US Food and Drug Administration-approved forms of medications for OUD (MOUD). Continuity of care through structured community-based treatment programs, mutual aid groups, and social supports are all protective factors in reducing overdose after incarceration.

States can mitigate some of the components that increase overdose risks by developing policies and structures that encourage or even require system intersections among corrections, health, behavioral health, and other support services.

Provide naloxone training and access to naloxone upon release. Given the established risk of overdose upon re-entry, access to the opioid-overdose reversal drug naloxone is critical (it has saved thousands of lives yearly), and can be facilitated by jail and prison staff with state support. Both large and small jail systems in locations such as Cook County, Illinois and Plumas County, California, as well as several counties in Maryland, have begun providing naloxone and naloxone trainings to all incarcerated individuals. Maryland’s state heroin and opioid task force recommended this approach in its 2015 report, and the state responded by developing a pilot in three localities that has since expanded. New York began providing naloxone and naloxone training through a 2015 pilot at one facility that was administered by the Department of Corrections and Community Supervision (DOCCS), with train-the-trainer support for corrections officers provided by the state’s Harm Reduction Coalition. As part of the effort to make naloxone more widely available for this program and in DOCCS overall, the agency became a state Opioid Overdose Prevention Program, a designation authorized by the New York Department of Health (DOH). As of 2021, naloxone for re-entering individuals is available at all 54 state prison facilities as part of the statewide distribution program, and correctional officers are required to initiate naloxone rescue in all correctional settings if overdose is indicated. Lawmakers in New Mexico passed a bill directing the state’s Department of Corrections to provide naloxone training and two doses of the drug to all re-entering individuals who have SUD diagnoses. Virginia’s Department of Corrections has indicated plans to implement a naloxone take-home initiative for all eligible individuals, which it will obtain through a partnership with the state’s Department of Health, which currently supplies naloxone for correctional officers.

Establish and strengthen cross-agency relationships to ensure systems and state-local coordination. Mitigating overdose risk requires coordination of services and providers both pre- and post-release, which means that disparate systems at both state and local levels must work collaboratively. Washington State’s Division of Behavioral Health and Recovery (DBHR) administers the long-standing Offender Re-entry Community Safety Program (ORCSP) that supports individuals both pre- and post-release (up to 60 months) from DOC facilities with services not covered by Medicaid. They include:

- Pre-release engagement

- Intensive case management

- Specialized treatment services (including SUD)

- Housing assistance

- Basic living expenses

- Transportation assistance

- Educational and vocational services

- Employment services

- Unfunded medical expenses, and

- Other non-medical treatment supports

Individuals are screened and recommended by DOC for program eligibility. A review committee co-chaired by DOC and DBHR and composed of representatives from the state Department of Social and Health Services, law enforcement, and other state stakeholders and treatment providers uses established program protocols to determine participation. The committee then refers participants to the appropriate community behavioral health resource to initiate care. The state maintains contracts with 12 community behavioral health providers and one behavioral health organization to provide these services. In a 2017 meta-analysis, the ORCSP had the most significant impact on reducing recidivism among all programs that support re-entering individuals in Washington State.

The Virginia Attorney General’s Office coordinates the state’s re-entry councils, which are guided by four primary principles: pre-release planning, interagency/governmental coordination, integrated service delivery, and positive links to community with family and community support. Having a state coordinating body creates some uniformity in composition and goals, while allowing individual councils to determine local needs and how they work with jails and prisons. Councils are composed of both public and private agencies that provide linkages to housing, employment, and health and behavioral health services, as well as faith-based resources and other wrap-around service needs. Virginia’s Department of Corrections currently reports the lowest recidivism rate for state responsible individuals in the country at 23.1 percent, and services and resources provided by these councils are cited by state leaders as contributing factors in re-entry success.

Connect individuals to health care access prior to release. Ensuring that Medicaid coverage is active for individuals who are re-entering assists in connections – not only to OUD treatment services – but also to primary care and other wrap-around services. This is an approach supported by the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS), as outlined in its 2016 guidance to states that responded to state questions about the challenges of coverage for the incarcerated population. Because they are statutorily prohibited from receiving Medicaid reimbursement for OUD treatment nor any other in-house medical services, most jails and prison correctional facilities rely on contracted providers paid through set state budgets and/or grants for treatment.

Forthcoming recommendations: The 2018 Substance Use-Disorder Prevention that Promotes Opioid Recovery and Treatment (SUPPORT) for Patients and Communities Act requires the establishment of a Medicaid Re-entry Stakeholder Group, the announcement of which was posted in mid-2020. The group will provide advice and recommendations to the Secretary of Health and Human Services on Medicaid policy supports for people who are incarcerated.

While states currently cannot use Medicaid to pay for services for incarcerated individuals, they can facilitate enrollment for those who are approaching release. This presents an opportunity to ensure that care is coordinated post-release, and that individuals who need to be connected to OUD treatment services are able to access treatment without payment barriers, particularly in Medicaid expansion states. In states that suspend (rather than terminate) Medicaid while an individual is incarcerated, coverage can be quickly re-instated upon release – a process made more efficient in states such as Arizona that foster a data exchange between the state department of corrections and the agency that administers Medicaid. Arizona requires contracted Medicaid managed care plans to have contacts in correctional settings for this purpose and provides a template for suspension of services.

States can also use managed care contracts to administer Medicaid “in-reach” programs or care continuity requirements that work with currently incarcerated individuals pre-release, forging inter-agency partnerships in conjunction with contracted health plans to facilitate enrollment. Ohio’s managed care contract agreements include a provision that plans must engage in the “development, implementation, and operation of initiatives for early managed care enrollment and care coordination for inmates to be released from state prisons,” a requirement that also applies to state psychiatric hospitals and the state’s juvenile facilities. This is in support of the state’s Pre-Release Enrollment Program, the result of a cross-agency partnership between the Ohio Department of Medicaid and the Ohio Department of Rehabilitation and Correction that began in order to develop processes for inpatient hospitalization coverage. This partnership grew over time, leading the agencies to create a first-of-its kind approach that serves all Medicaid-eligible inmates, allowing them to select a managed care plan prior to release. The plan then assesses their needs and identifies potential providers, coordinating care upon re-entry.

New ideas are emerging from states to use Medicaid as a lever to ensure treatment continuity. Utah has also taken this one step further, submitting a waiver proposal to CMS that would provide coverage for individuals with OUD and other chronic and behavioral health conditions 30 days prior to their release. The proposal notes that service reimbursement for inmates during pre-release is anticipated to reduce emergency department use and hospitalizations, resulting in reduced costs to Medicaid for care in the community. The state poses this as an opportunity to create a policy environment in which treatment initiated in correctional facilities can remain essentially uninterrupted, continuing seamlessly into the community.

At the direction of the state legislature via budget bill language in 2020, Kentucky has submitted a similar 1115 waiver proposal specific to incarcerated individuals with SUD. This proposal caps the number of program participants over each year of the demonstration and proposes a weekly bundled payment for services. Approval of this approach would represent a significant shift in both treatment and payment opportunities for states.

Release from Incarceration – the Critical Re-entry Period (Intercept 4) – Key Highlights

- Provide re-entering individuals with naloxone by establishing partnerships among jails, state and local public health agencies and agencies that provide training.

- Formalize relationships among stakeholder and government entities necessary to develop responsive re-entry policies and to ensure that the right services are available to address the needs of re-entering individuals with OUD.

- Optimize Medicaid processes to help individuals who are incarcerated gain or re-establish health care coverage that is able to be accessed immediately upon their re-entry.

Continue OUD treatment that was initiated during incarceration by developing protocols for treatment stability in the community.

Most people who are corrections-involved are supervised in the community by local agencies – about 80 percent through probation programs and 20 percent by parole programs. Similar to incarceration rates, inequities by race persist within these groups as well – recent data from the Bureau of Justice Statistics indicates that 30 percent of individuals in probation and 37 percent of those in parole programs were Black, despite composing only 13 percent of the US population.

Community corrections services support individuals on both margins of incarceration – as a diversion strategy to keep people from incarceration and for those who have re-entered the community. A high rate of substance use disorder (SUD) among individuals under community corrections oversight indicates that this population can benefit from targeted, evidence-based treatment, and intensive support services that can prevent criminal violations and at the same time address the underlying SUD. Incorporating treatment into community corrections, especially through collaborative systems of care that integrate both supervision and a range of SUD and behavioral health interventions, is effective in reducing both substance use and criminal behavior. Creating those systems, however, can be challenging for states, as community corrections services are administered by public safety or judicial entities with the authority to sanction individuals for violating the terms of their release – including substance use. States are working to bridge this cultural and procedural disconnect by integrating policies and programs that emphasize treatment access and supportive services.

Provide training on evidence-based treatment for probation and parole officials. SUD-focused training for community corrections officers can support connections to treatment by addressing:

- Gaps in knowledge about evidence-based treatment;

- The relationship between SUD and criminal legal system involvement; and

- The community-based options for treatment.

Recognizing the need for cross-systems collaborations to address the factors that foster SUD, the American Probation and Parole Association (APPA) advocates for a training approach that includes intentional coordination with treatment partners and education for specialized SUD officers.

Use of medication for opioid use disorder (MOUD) as a treatment component has been shown to reduce recidivism, a core goal of community corrections. Stigma or lack of information about MOUD can sometimes undermine corrections officers’ support for medications as part of supervision. Officers may also see medications as a potential diversion risk. A majority of probation department leaders, however, report receiving little to no training on MOUD, indicating that education and training such as the Residential Substance Abuse Treatment (RSAT) Training Tool on MAT for Offender Populations, published with funding support from the Bureau of Justice Assistance (BJA) SUD intervention grant program, may help support treatment to this population.

Develop protocols for probation violations that emphasize treatment when necessary. A breach of an individual’s conditions of release can lead to sanctions that include incarceration or re-incarceration. This is exceedingly common, a 2019 analysis of the financial impact to states of supervision violations showed that 45 percent of state prison admissions were for new offenses or “technical violations,” which include positive drug screens. These supervision violation admissions contribute to more than $9.3 billion in incarceration costs incurred annually across states. In addition to leading to a costly cycle of re-incarceration for states, prison admissions that result from positive drug screens may also indicate a need for treatment to disrupt that cycle. One approach that addresses this need is to sanction individuals with violations into a drug court program (see Intercept 2) or an incarceration setting that specifically provides treatment to this population.

Pennsylvania’s Department of Corrections (PA DOC) implemented this approach in 2019 to a limited group of sanctioned individuals who were clinically indicated for induction on buprenorphine. While some form of MOUD has been available across the state’s incarceration system since 2018, injectable buprenorphine was first provided specifically to individuals on community supervision who were reincarcerated as a result of an opioid-related technical violation. Under a single-site pilot implemented in 2019, Pennsylvania introduced injectable buprenorphine in this population, providing oral buprenorphine followed by the long-acting injection prior to release. Participants continue on treatment in the community on release to community supervision in either an inpatient or outpatient treatment program.

Build dedicated residential treatment programs into community corrections. Intensive treatment supports in non-secure facilities and stepped-down release programs are a strategic way to integrate treatment into correctional programs for individuals on supervision. Delaware’s residential treatment program, formerly called Key-Crest and revised in late 2020 as the restructured program, Road to Recovery (R2R), follows three “tracks” to streamline treatment depending on individuals’ SUD severity. Delaware’s approach begins treatment while individuals are incarcerated, moving through community corrections, and ultimately to community recovery and aftercare. Behavioral health services along this continuum are provided through a contract with Centurion of Delaware, a correctional health care organization that contracts separately with the Delaware Department of Corrections (DDOC) for medical services. The three-year behavioral health contract, signed in April 2020, specifies that individuals participating in SUD programming will receive treatment that aligns to the American Society of Addiction Medicine (ASAM) criteria for levels of care, requiring ASAM Level 3 services for residential treatment, ASAM Level 2 services for intensive outpatient treatment, and ASAM Level 1 services for outpatient treatment in aftercare programs. Transitional services including recovery housing referrals, connections to medical coverage, and continued MOUD treatment are stipulated as necessary components of care to be delivered to Delaware’s treatment program participants. In order to further develop peer service integration, the contract also directs that Centurion will plan and implement a forensic peer program in which currently incarcerated individuals are trained to provide peer support while part of the program.

Provide naloxone to probation and parole officers. While this is not a direct treatment strategy, making naloxone available to community corrections officers and in community corrections settings can be lifesaving for people with OUD, as supervising officers are in regular contact with individuals who are at higher risk of overdose.

Supplying their offices with naloxone and training officers on how to use it can help those officers intervene in the event of an overdose. In 2019, Virginia’s legislature added probation and parole officers to the statutory list of professionals designated to be trained and in possession of naloxone, a law that includes immunity in the event of an injury. The state’s Department of Corrections (VA DOC) subsequently issued policy procedures requiring probation and parole offices to develop plans to outline implementation and operational procedures for the administration of naloxone. The VA DOC pharmacy purchases naloxone via an agreement with the Virginia Department of Health and supplies offices once all staff can show proof of training.

Community Corrections (Intercept 5) – Key Highlights

- Train community corrections officers on the nature of SUD and the evidence-based options for treatment to increase the use of MOUD and treatment supports as part of community supervision.

- Recognize substance use-related treatemtn violations as indications that an individual requires a higher level of SUD intervention and treatment.

- Develop residential programs for community supervision that integreate SUD treatment into the community corrections continuum.

- Provide naloxone to community corrections officers.

Treatment for Incarcerated Individuals

People with opioid use disorder (OUD) who are incarcerated are often abstinent from substances upon their release, though without evidence-based treatment, they are over 12-times more likely to die of an overdose within two weeks of release than the general population. Re-entry is itself a risk factor for people with OUD – and many jails and prisons are releasing individuals early due to the pandemic, increasing the need for people to receive evidence-based treatment while incarcerated.

- Opioid Use Disorder Treatment: How Vermont Integrated its Community Treatment Standards into its State Prisons

Many with opioid use disorder (OUD) are incarcerated for drug-related crimes, without access to treatment, which increases their risk of overdose death following release. Vermont extended its statewide Hub and Spoke treatment model into its corrections system to provide best OUD treatment practices, which includes medication-assisted treatment. - Litigation Prompting State and Local Correctional Systems to Change Opioid Use Disorder Treatment Policies

Recent litigation involving state and local jails has contributed to mandates for access to medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) for people who are incarcerated. Incarceration-based MOUD programs are associated with taxpayer savings, lower crime rates, and lower drug-related incarceration costs. - Q&A: How Maine’s County Jails Collaborated with the State to Develop a Shared Substance Use Disorder Treatment Model

As part of the state’s opioid crisis response, Maine has prioritized providing OUD treatment to its incarcerated population. Maine’s county jails, which are separate from the state prison system, worked with the state Department of Corrections to develop a medication-assisted treatment (MAT) model now used by all county jails. - State corrections leaders are increasingly embracing models of treatment that include medications for opioid use disorder (OUD) in incarceration settings, recognizing that treatment for individuals with OUD is effective and contributes to reductions in overdose deaths. This NASHP report, Three Approaches to Opioid Use Disorder Treatment in State Departments of Correction, highlights incarceration-based treatment programs in Maine, Kentucky, and Pennsylvania.

- NASHP Webinar: State Approaches to Incarceration-Based Treatment for Opioid Use Disorder. This webinar recording features state correctional leaders from Maine and Pennsylvania who implemented incarceration-based treatment for OUD programs.

- NASHP Chart: Medications for Opioid Use Disorder (MOUD) Provided in State Prisons, March 2021. Many states provide medications for opioid use disorder (MOUD) to individuals incarcerated in their state prisons. The three current MOUD options approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) include methadone, buprenorphine, and naltrexone. This chart shows what MOUD each state provides. Please email updated information to emette@nashp.org.

Acknowledgements: The National Academy for State Health Policy is providing this toolkit with the ongoing support of the Foundation for Opioid Response Efforts (FORE) and thanks FORE Project Officer Ken Shatzkes and FORE President Karen Scott for their continued guidance and direction. The authors would also like to thank state leaders from Maryland, New York, North Carolina, Oregon, Rhode Island, Vermont, and Virginia for sharing their expertise and state experience implementing innovative health policy initiatives, as well as state officials from Alabama, Ohio, Pennsylvania, and Washington State, who generously shared their time and insights in reviewing this material.