You are viewing one section of the Public Health Modernization Toolkit. Please check out the other two sections:

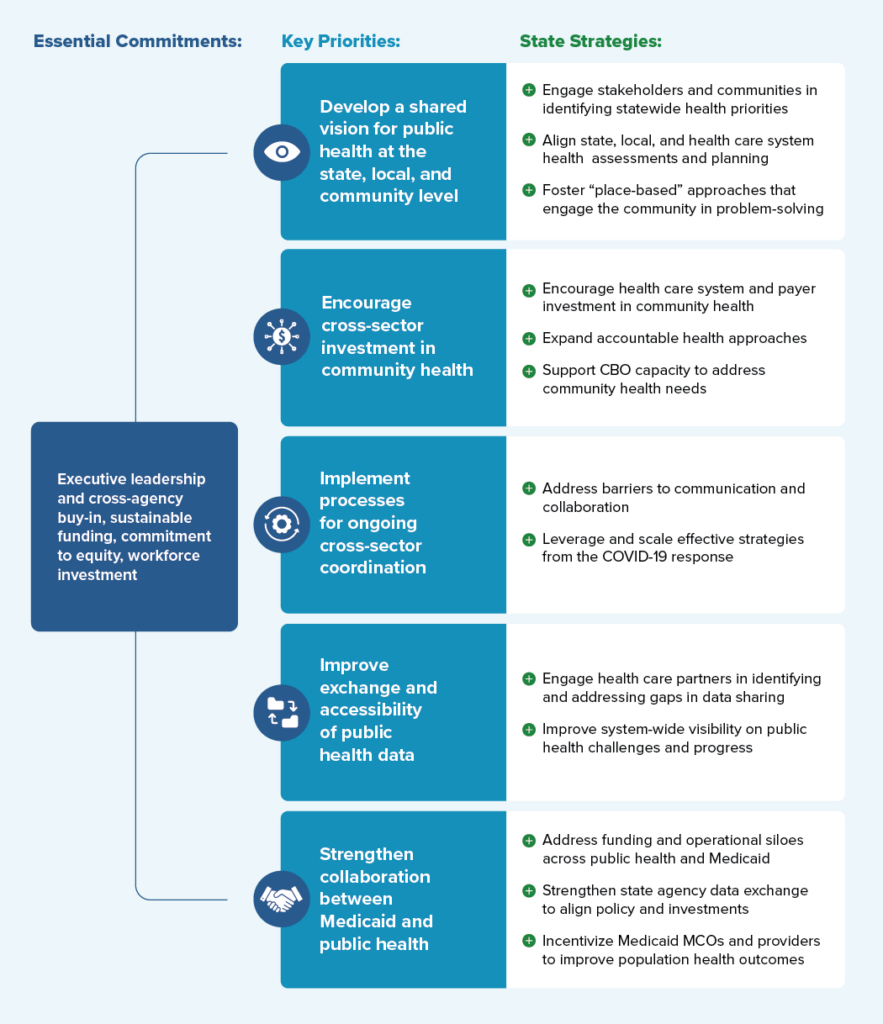

Drawing on interviews with cross-agency state leaders and public health experts, local leaders, and scientific and grey literature, this toolkit provides a framework for understanding essential commitments, key priorities, and policy strategies for fostering collaboration among public, private, and community partners to improve population health outcomes.

Figure 1 displays a consolidated overview of the “Framework for Public Health-Health Care System Collaboration.” Specific examples taken from a variety of states will be examined in greater detail throughout the toolkit.

Figure 1: Public Health-Health Care System Collaboration Framework

Essential Commitments for Supporting a Modernized and Connected Public Health Care System

Robust partnerships between public health and health care systems — capable of sharing information that enables effective population health interventions to stop the spread of disease, increase access to care, or prevent injuries — are a vital part of the public health infrastructure needed to meet community needs. A precondition of sustaining these partnerships is sustained investment in state and local public health capacity. Policymakers and public health experts have widely acknowledged the longstanding challenges in the current public health system stem from both chronic underinvestment and cycles of “panic and neglect” in reaction to public health crisis. Funding for state and local health departments decreased 17 percent between 2009 and 2019, while experts estimate that an additional $4.5 billion per year is necessary to ensure access to basic public health services.[1] On a federal level, experts continue to call for a re-envisioned national public health system supported by sufficient, predictable, and flexible public health funding to support core programming and basic public health capacity.

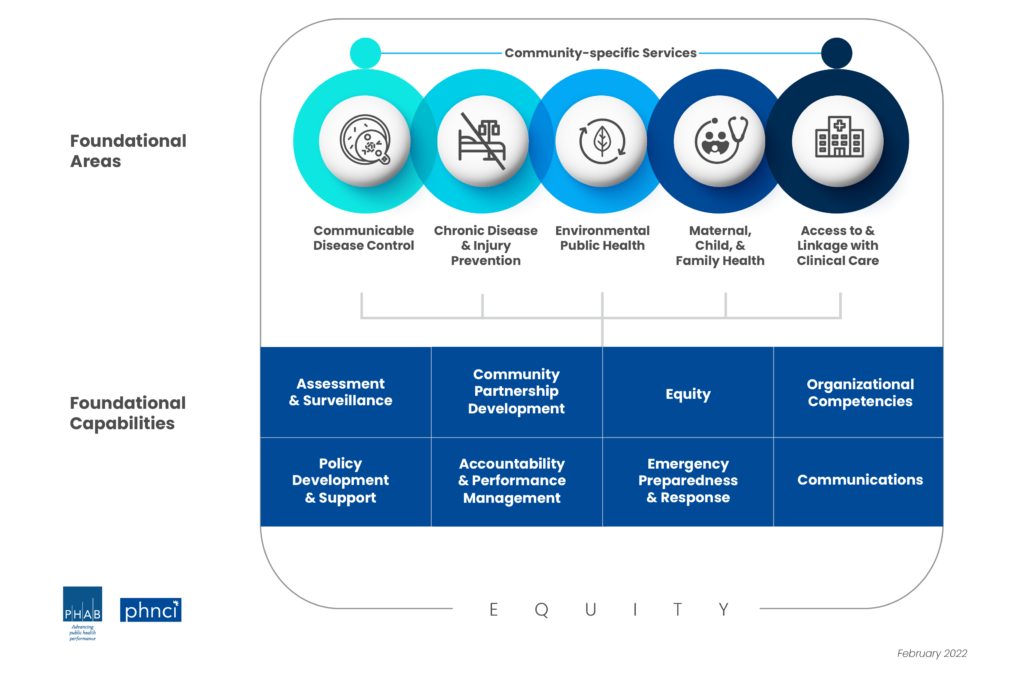

The minimum set of foundational public health capabilities and programs that should be available in every community are defined by the Public Health National Center for Innovations (PHNCI) Foundational Public Health Services (see Figure 3).

Figure 3: PHNCI's Foundational Public Health Services (FPHS)

Source: PHNCI

On a state level, effective leadership with a sustained commitment to public health is equally important to ensuring that progress and investments made in public health systems in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic are sustained. According to interviewed state leaders and experts, the following are essential commitments necessary to ensure that effective strategies and bridges built between cross-sector partners can be sustained into the future:

- Leadership: Governors and health agency leadership play important roles in setting priorities, convening persons or groups who have an interest in a project, targeting resources, and overseeing implementation and progress of initiatives over time.

- Funding: Commitment to sustainable funding approaches at the federal and state level are necessary for agencies to operationalize foundational capabilities, thereby ensuring organizational excellence, building public trust, and delivering on essential public health services.

- Workforce: With an estimated 80,000 additional state and local health agency positions needed to deliver a minimum level of public health services, it is crucial to develop long-term plans to recruit, train, hire, and retain a future public health workforce with the skills needed to address future challenges. Creative workforce solutions that focus on bridging health care and public health can emerge from comprehensive workforce assessments that map on to effective interventions.

- Equity: A commitment to prioritizing health equity and reducing health disparities includes actively partnering with communities in the policy and decision-making process to ensure that a modernized public health system not only reaches every community, but also meets its needs.

While these essential commitments are a necessary pre-condition to sustain basic public health system capacity, specific priorities and strategies for better engaging healthcare system partners on shared public health priorities are outlined in the sections below.

Building and Sustaining a Robust Public Health Workforce

Public health workforce assessments such as the de Beaumont Foundation and the Public Health National Center for Innovations (PHNCI)’s Staffing Up Initiative and the Public Health Workforce Interests and Needs Survey outline many of the ongoing challenges for the public health workforce, including underinvestment, difficulties in recruiting and retention, and burnout and mental health challenges.

Through the CDC’s Strengthening U.S. Public Health Infrastructure, Workforce, and Data Systems grant program, the CDC will award more than $4 billion to states, localities, and national partners over five years to strengthen public health systems with a focus on workforce, strengthening foundational capabilities, and data modernization. The Association of State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO), National Network of Public Health Institutes, and Public Health Accreditation Board, in partnership with NASHP and other public health partners, will provide technical assistance to states and local jurisdictions receiving infrastructure funding.

Additional tools and resources at the national level that states can leverage to support public health workforce include:

- The Council on Linkages between Academia and Public Health Practice: Core Competencies for Public Health Professionals and Public Health Agency Toolkit.

- PHNCI: The 21c Learning Community supports states with identifying the foundational public health services, assessing and costing their provision, and implementing actionable transformation frameworks and models.

- Staffing Up Workforce Calculator allows agencies to model existing expenditure and staffing data to determine public health workforce needs.

- Public Health Foundation: TRAIN Learning Network is a large-scale learning management system specifically tailored for the public health workforce.

Key Priority: Develop a Shared Vision for Public Health Priorities at the State, Local, and Community Level

Whether states are re-envisioning their public health systems, implementing a State Health Improvement Plan (SHIP), or crafting an interagency approach to a specific health challenge, governors and health agency leadership can help articulate and elevate public health priorities, as well as ensure meaningful engagement processes that promote shared ownership of goals. State leaders play a critical role in convening key internal and external partners, implementing engagement and input processes that foster shared ownership and accountability toward goals at the state and community levels. The following strategies are examples of how states have worked to meaningfully engage partners and communities in developing a “vision” for public health at the state, local, and community level; how states have worked to better align state, local, and health care system-led community assessment and planning efforts; and how states are supporting models for engaging communities in identifying and addressing health priorities.

State Strategy: Engage Partners and Communities in Identifying Statewide Health Priorities

As outlined in State-Level Examples of Engaging Partners and Impacted Communities in the Development of Public Health Priorities, there are a variety of existing processes at the state level for identifying statewide population and public health priorities, each with their own methods for integrating existing data as well as input and feedback from interested partners and impacted communities. In many states, SHIPs serve as the driving mechanism for engaging health care systems and communities in statewide planning, implementation, and evaluation efforts. Many state and community health planning efforts use the Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships (MAPP) framework, a strategic planning process that emphasizes broad partner and community engagement, systems change, and the alignment of community resources toward shared goals.

Building in processes for meaningful, culturally informed engagement and ongoing bi-directional communication with diverse partners and impacted communities can help facilitate buy-in and trust and contribute to policies that are more effectively tailored to community needs. Promising examples of processes to engage partners in state health planning and decision-making include:

- The Indiana Governor’s Public Health Commission livestreamed all proceedings, maintained a public comment website, held seven public “listening tour” meetings in geographically diverse location and conducted more than 30 “stakeholder meetings” to gather input and maintain transparency for the Commission’s final report and recommendations.

- At the center of the Washington State Department of Health’s (WSDOH) transformational plan are five priority policy areas: health and wellness, health systems and workforce transformation, environmental health, emergency response and resilience, and global and one health. With a goal of supporting robust networks of information-sharing, strategy development, and engagement across governmental and public health system partners, WSDOH sought feedback from partners prior to developing these priorities. Feedback from internal and external partners allowed the department to build out six key strategies for each priority based on information from partner conversations and internal strategy sessions. The WSDOH’s transformational plan is a framework to foster continued conversation and collaboration on initiatives and projects that move the strategies to action.

- Through Michigan’s Public Health Advisory Council, the state facilitated structured interviews with a large range of invested partners (both traditional and non-traditional) to inform decision-making around state public health priorities. Interviewees shared a range of perspectives, including those of local health departments, the state’s sheriff’s association, the state medical society, community health centers, hospital and primary care associations, funders, a CBO, aging and assisted living partners, consumer advocacy groups, and legislators.

- Oregon convened over 60 partner organizations as part of its SHIP development process and contracted with CBOs to collect community feedback. This feedback, along with state-collected health data, helped shape Oregon’s five priority areas: institutional bias; adversity, trauma, and toxic stress; behavioral health; access to equitable preventive services; and economic drivers of health.

State-Level Examples of Engaging Partners and Impacted Communities in the Development of Public Health Priorities

State Health Improvement Plans (SHIPs): 48 states currently develop their own SHIPs through collaborative, multi-stakeholder processes designed to set the state’s health priorities, target resources, guide programs and policies, and drive collaborative efforts. State health assessments, such as those conducted by Ohio, Alaska, and Pennsylvania, help inform the development of SHIPs and the assessment of progress on state health priorities by providing an overall picture of state health and well-being across key health metrics.

Public health transformation: In states such as Ohio, Oregon, Washington, and Kentucky, public health transformation efforts have driven collaborative processes to define core public health services, assess existing and needed capacity to deliver these services, identify financing and implementation strategies, and define accountability metrics.

Governor and agency-led initiatives: Governors, first spouses, and other statewide leaders have wide authority to elevate key issues and convene partners around common goals. In Indiana, Governor Eric Holcomb charged a Public Health Commission with assessing Indiana’s public health system capacity and developing recommendations for improving capacity, preparedness, equity, and sustainability. Nurture New Jersey, First Lady Tammy Murphy’s office initiative on improving maternal and infant health outcomes, brings together the office, leadership from 18 state agencies, and a broad coalition of maternal and child health partners to reduce maternal and infant mortality, particularly for women of color.

State Strategy: Align State, Local, and Health Care System Health Assessments and Planning

Several states have worked to harness public and private investments in community capacity by aligning hospital community benefit activities with goals identified through SHIPs and Community Health Improvement Plans (CHIPs). Under the Affordable Care Act, the IRS requires nonprofit hospitals to conduct a community health needs assessment (CHNA) and develop a community benefit implementation plan every three years. Such efforts can ensure that community health planning does not occur in silos; that public health, community, and health care systems are all at the decision-making table; and that partners work together to maximize investments. Some key examples of aligning hospital and health care system investment with community needs include:

- Ohio’s participation in a multi-year State Innovation Model initiative spurred discussions between the Governor’s Office of Healthcare Transformation, Ohio Department of Health (ODH), and public health and health care system partners around strategies to address upstream social determinants of health. Partners identified the misalignment of local health districts’ five-year community health planning cycles with hospital systems’ three-year CHNAs and planning cycles as a barrier to coordination on health goals. State leaders worked with the legislature to align local health district and hospital community planning efforts on three-year cycles. Following this legislative change, ODH issued guidance to local health districts and nonprofit hospitals to support improved coordination, planning, and investment across state and local health department and hospital community health activities.

- New York requires that nonprofit hospital community benefit plans address and report investments in community health interventions tied to the state’s Prevention Agenda 2019–2024.

- The Virginia Department of Health (VDH) partnered with the Virginia Hospital & Healthcare Association (VHHA) on a Partnering for a Healthy Virginia initiative, which coordinates efforts between VDH, VHHA hospitals and health care systems, local health departments and jurisdictions, and other health care partners to prioritize and develop strategies for improving population health needs as identified by CHNAs.

State Strategy: Foster “Place-Based” Approaches that Engage the Community in Problem-Solving

Communities are typically in the best position to understand and develop solutions to their own health challenges. Partnering with communities can result in increased efforts at a state level to support “place-based” approaches that engage communities in taking a holistic look at community needs and leveraging investments across multiple domains to maximize impact. A collective impact approach provides a model for bringing public health, community members, civic leaders, businesses, health care systems, and other invested partners together to identify community needs and work together toward systems level change. Within a collective impact model, an empowered backbone entity (often a local health department, charitable organization such as United Way, or community-based organizations) plays a central coordinating role in convening and engaging this wide network of community organizations and partners to develop a collectively defined agenda and support ongoing communication, coordination of efforts, measurement, and accountability toward goals.

Such approaches can be powerful tools, helping communities engage with public health and health care system partners to address health concerns and needed interventions such as improving access to high-quality preventive services and addressing social, economic, and environmental factors that affect community health. Although many collective impact models operate on the local or community level, states can play an important role in convening partners, supporting and providing technical assistance to backbone entities, and giving the financial support needed to sustain such approaches.

Innovative approaches such as Health Equity Zones (HEZ) can provide models for empowering place-based, community-led strategies to address community-identified problems and priorities and set the signal for cross-sector collaboration. The Rhode Island Department of Health (RIDOH), in collaboration with state agency and community partners, identified 15 indicators of health equity. A braided funding model, leveraging both categorical public health funding and private and philanthropic investments, allows community collaboratives to have flexibility in identifying and addressing community priorities.

Through dedicated project officers, RIDOH supports community collaboratives with ongoing resources and technical assistance for implementing the HEZ model, including support for the “backbone organization” that manages the ongoing planning, implementation, and financial management of HEZ activities. With Medicaid covering 55 percent of children and 28 percent of adults in Rhode Island, the state is examining strategies to support the scaling and sustainability of HEZs — including aligning with Medicaid and accountable entities approaches with their continued emphasis on braided funding to address health-related social needs and community health. Centering community voices, aligning sectors, and fostering partnerships to support transformational change is also at the heart of the Accountable Communities for Health model (discussed in subsequent sections of this toolkit). Financing mechanisms, including blending and braiding funding streams and accountable health approaches, are often central to bringing together diverse partners and community members to implement and sustain place-based approaches.

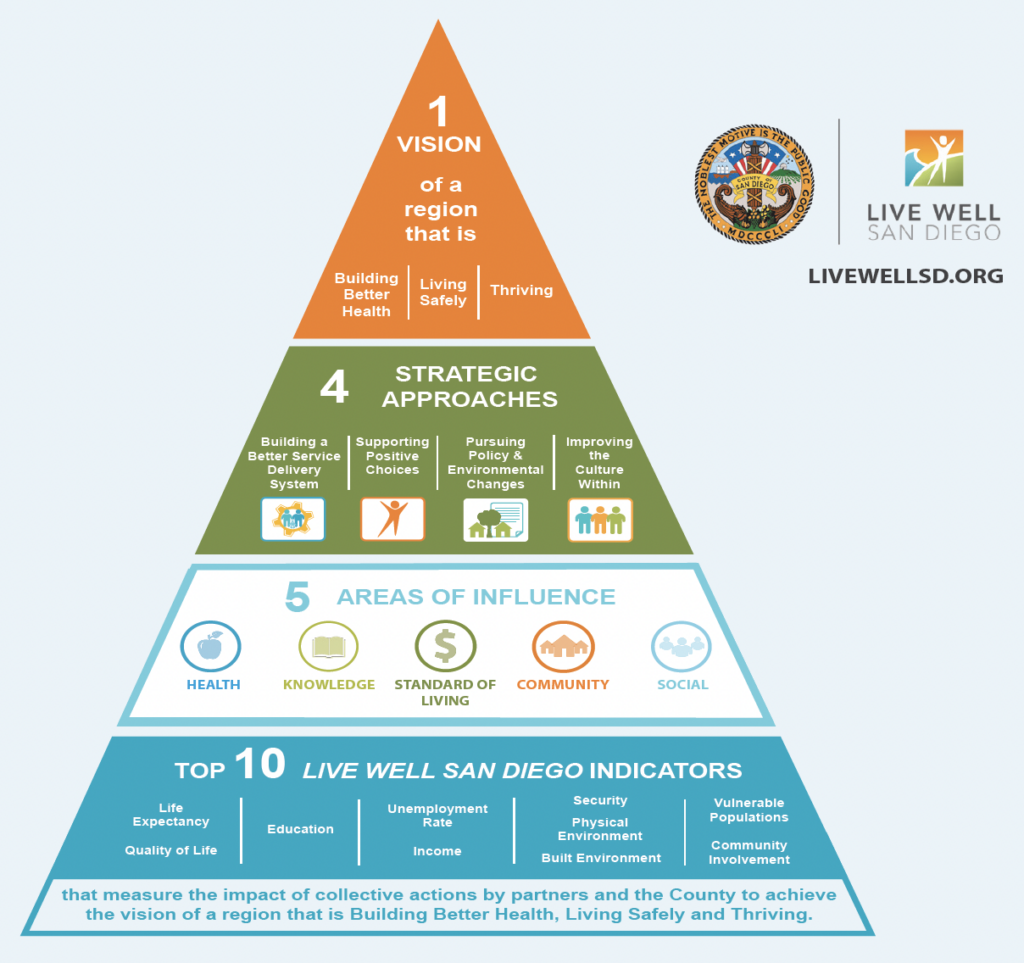

A Local Collective Impact Model for Improving Health Outcomes

The collective impact model has been implemented to address a variety of environmental, educational, and social challenges, and it has also been successfully implemented across jurisdictions to align public health, health systems, business, and community leaders around common population health goals. One example is Live Well San Diego. Through the backbone entity of the County of San Diego, Live Well San Diego aligns cross-sector stakeholders from over 500 organizations, governments, businesses, school districts, and other community partners around a shared vision of helping all San Diego County residents live healthy, safe, and thriving lives. Collectively partners address behaviors, policies, and environmental conditions that contribute to the four diseases (cancer, heart disease and stroke, Type 2 diabetes, lung disease) that account for 50 percent of deaths in San Diego County. Through coordinated efforts to track progress and advance programs and initiatives to improve quality of life in the region, Live Well San Diego was able to drive a 12 percent reduction in the percentage of deaths associated with preventable health threats between 2007 and 2019 among San Diego County residents.

Resources

- CMS: Opportunities in CHIP and Medicaid to Address Social Determinants of Health (SDOH)

- Funders Forum on Accountable Health

- NACCHO: Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships

- NAM: Assessing Meaningful Community Engagement: A Conceptual Model to Advance Health Equity through Transformed Systems for Health

- Rhode Island Department of Health: Health Equity Zones: A Toolkit for Building Healthy and Resilient Communities

- SHVS: Transformational Community Engagement to Advance Health Equity

Key Priority: Encourage Multi-Sector Investment in Community Health

Public health services are often delivered at the local and community level. Both Public Health 3.0 and the Commission on a National Public Health System’s “Meeting America’s Public Health Challenge” report envision a future for public health in which state and local health departments (LHDs) “engag[e] multiple sectors and community partners to generate collective impact.” In keeping with “partnership development capacity” as a foundational capability of public health, LHDs are often well-positioned to know their communities, develop relationships, and serve as backbone entities/connectors to bring partners and community voices together. Public health transformation efforts in several states have provided a framework for strengthening the ability to assess local public health’s capacity to deliver foundational health services, along with strategies to address financial gaps or programmatic challenges.

In addition to the importance of strengthening local public health capacity, COVID-19 made clear that community-based health care providers and CBOs are themselves a critical part of the public health infrastructure required to meet the needs of communities. As health care payers and systems increasingly invest in upstream, community-level interventions to improve population health outcomes, states can both encourage multi-sector investment into this community health infrastructure and play a coordinating role in making sure these efforts are aligned. The following are strategies that states are using to encourage and align investments across the public and private sectors to strengthen community public health infrastructure and capacity.

State Strategy: Encourage Health Care System and Payer Investment in Community Health

As discussed in the previous section on integrating health care system partners into health assessments and planning, states have a variety of legislative and regulatory levers to encourage community investment from health care systems and payers and to ensure that those dollars are directed toward community-identified needs. To promote accountability for community investments and encourage health care system partners to better engage public health and community partners on spending priorities, states have employed a number of strategies, including setting a minimum level of community reinvestment from Medicaid managed care organizations (MCOs) or community benefit spending from nonprofit hospitals.

With new CMS guidance on innovative options for managing Medicaid managed care programs to address health-related social needs, states are implementing different strategies to reduce health disparities and invest in community supports. One example is the inclusion of specific “in-lieu-of” services options in MCO contracts as a substitute for services or settings covered in the state plan. For instance, as part of California’s Medicaid transformation initiative, CalAIM, health plans can reimburse for asthma remediation services as one of 14 community supports. Medicaid programs can also use contracting levers to encourage health plans to cover additional services by providing guidance on value-added services. States also may offer flexibility, allowing MCOs to include community benefit activities as covered services in calculating their medical loss ratio. By federal law, health plans are required to spend no more than 15 percent of total capitation revenue on activities such as administration, reserves, and profit. Allowing MCOs to count community investment activities as covered services rather than administrative can incentivize these activities.

Several states use contract provisions that require MCOs to partner with specified community entities and align with Community Advisory Councils or Community Health Improvement Plans. Some examples of leveraging Medicaid contracting to support community investment include:

- In Pennsylvania, physical health MCOs are limited to 3 percent excess revenue annually with the option to retain a portion of additional revenues by investing in approved projects that directly benefit communities, including initiatives that address social determinants of health (SDOH).

- In Ohio, the Department of Medicaid requires MCOs to contribute 3 percent of their annual after-tax profits to community reinvestment, and the percentage of contributions must increase by 1 percentage point each subsequent year (max of 5 percent). MCOs must prioritize community reinvestment opportunities generated from community partners. Additionally, MCOs are required to collaborate with other MCOs and evaluate impact of community reinvestment efforts.

- Through Oregon’s SHARE initiative (Supporting Health for All through Reinvestment), coordinated care organizations (CCOs) must spend a portion of their net income on social drivers of health (SDOH) and equity efforts in their community. Investments with community SDOH partners must be based on priorities in the CCO’s current Community Health Improvement Plan (CHP), include a role in spending decisions for the CCO’s community advisory council (CAC), fit into one of four domains (economic stability, neighborhood and built environment, education, and social and community health), and address the Oregon Health Authority-designated Statewide priority (currently housing).

State Strategy: Expand Accountable Health Approaches

Amidst the shift toward greater accountability for patient outcomes, accountable health payment models have emerged as promising tools. Such models can incentivize health, public health, and social service partners to work collectively to address health-related social needs and work to improve population health outcomes. States interested in expanding accountable health approaches have a variety of strategies at their disposal, including the Accountable Communities for Health (ACH) model and accountable care organizations (ACOs).

The ACH model (also referred to as coordinated care organizations, or accountable health communities) creates “multisector partnerships that seek to improve health outcomes by addressing health-related social needs at the individual level and social determinants of health (SDOH) at the community level.” Over 100 ACH or ACH-like entities exist in the U.S., and models are being tested in 21 states, with the goal of promoting clinical-community linkages to address health-related social needs, improve outcomes, and reduce costs. By design, ACHs generally create a governance structure inclusive of community members and organizations and share data across sectors to measure progress for communities. Typically, ACHs are guided by a common vision developed through community engagement and partnership and led by a backbone organization responsible for community engagement, strategic planning, and program evaluation.

ACHs are both publicly and privately funded and often are part of payment and delivery system reforms that aim to achieve whole-person care. States can finance ACHs through a variety of mechanisms, including blending and braiding federal and philanthropic funding, use of Medicaid state plan benefits, utilizing MCO contracting authorities, and proposing Medicaid 1115 waiver demonstrations. Some states have taken on health care transformation through State Innovation Models (and built on these foundational initiatives)[2], Medicaid waivers, or other mechanisms, with accountable health entities providing a framework and means to integrate population health priorities into health care. Key examples include:

- Washington state established nine regional Accountable Communities for Health. Washington’s ACHs are independent local collaboratives that bring together local and tribal leaders, health care providers, payers, CBOs, social service providers, schools, and the justice system to address community-identified challenges through cross-sector collaborations and investments. This system grew out of a State Innovation Model planning and testing grant and a 2017 1115 DSRIP Waiver that allowed designated entities to earn hospital incentive payments by implementing projects that support care transformation. Since their inception, ACHs have invested over $225 million into local clinical and social service providers, with a focus on integrating physical and behavioral health, reducing the overuse of emergency departments, improving community-based care coordination, and meeting the demands of the COVID-19 pandemic.

- New Jersey operates Regional Health Hubs, which are nonprofit organizations that work closely with regional constituents and are dedicated to improving health care delivery and health outcomes. Health Hubs grew out of the state’s Medicaid Accountable Care Organization Demonstration Project. In 2020, state legislation established four hubs: Camden Coalition, Trenton Health Team, Greater Newark Healthcare Coalition, and Health Coalition of Passaic County. Each Regional Health Hub operates its own health information exchange, supports care management, convenes community partners to determine priority initiatives, and advises the state on regional needs. Recent hub priorities include addressing maternal health outcome disparities, improving access to cancer screening and treatment, and preventing tobacco use, among other focus areas.

Resources

- Braiding and Blending Funds to Support Community Health Improvement: A Compendium of Resources and Examples

- CMS SDOH Guidance

- CMS Quality Improvement Initiatives

- Center for Health Care Strategies: Advances in Multi-Payer Alignment: State Approaches to Aligning Performance Metrics across Public and Private Payers

- Funders Forum on Accountable Health

State Strategy: Support Community-Based Organization Capacity to Address Community Health Needs

Both state and health care system leaders have increasingly recognized the importance of CBOs and a community-based workforce, such as community health workers (CHWs), as providing important linkages with communities to address unique local needs. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, CBOs were engaged as a part of the community public health infrastructure for delivering vaccines, testing, and treatments. Engaging CBOs that had a footprint in and knowledge of the community promoted equity, helped garner trust, and reduced barriers to care for individuals who may be distrustful of public health or health care officials or otherwise lacked access to services. In an increasing number of both public health and health care delivery system initiatives, CBOs are integrated as service providers delivering a range of clinical and health-related social supports.

CBOs eager to participate in these efforts may face structural barriers to participating as full partners and therefore can benefit from state investment in capacity building. Many CBOs face small operating margins and limited financial reserves, as well as limited capacity to invest in the technology infrastructure and workforce needed to support marketing, contracting, and billing for health-related services. Most operate on grants and other prospective payment as opposed to reimbursement models (such as Medicaid billing). Cultural and language divides, as well as a history of distrust between mission-driven CBOs, governmental public health, or for-profit health care systems, may also complicate integration of CBOs into these efforts.

To support the growing role of CBOs as part of the public health and health care system infrastructure, states have developed a number of approaches for providing CBOs with technical assistance and capacity-building support:

- Oregon is working to build trusted relationships with CBOs and elevate community health priorities as part of the state’s commitment to eliminate health inequities by 2030. Building on CBO partnerships developed through the COVID-19 response and to advance the goals of public health modernization, the Oregon Health Authority (OHA) announced a new funding opportunity for CBOs, using braided funding from eight programmatic areas to support CBOs in addressing community-identified goals. As part of OHA’s “partnership development” work, OHA supports participating CBOs with continuous learning opportunities by contracting with the Oregon Nonprofit Association to provide technical assistance and support for common challenges in nonprofit management, including human resources, fiscal management, and grant writing.

- Officials administering Kentucky’s State Opioid Response grant contracted with a nonprofit partner that provides training, technical assistance, and support for CBOs delivering overdose prevention and harm reduction services to communities at the highest risk of opioid overdose. The Foundation for a Healthy Kentucky works with the state to lower barriers for CBOs to compete for and utilize state funding.

- California’s Providing Access and Transforming Health (PATH) initiative supports the goals of California Advancing and Innovating Medi-Cal (CalAIM) in transforming California’s Medicaid (Medi-Cal) program to provide more equitable, coordinated, and person-centered care. Specifically, PATH supports CBOs, public hospitals, county agencies, tribes, and other community partners to develop the infrastructure and capacity to deliver housing services, medically tailored meals, sobering centers, and other services included in Medi-Cal’s Enhanced Care Management (ECM) and Community Supports As part of PATH’s Capacity and Infrastructure Transition, Expansion, and Development initiative, CBOs that contract with MCOs can receive funding for activities such as purchasing new billing and data reporting systems and recruiting, hiring, and onboarding staff. Medi-Cal also provides CBOs with technical assistance and planning support for contracting and billing. Local public health departments providing ECM and community supports are also eligible for funding, and local public health officials are among the required participants in local PATH collaboratives.

Key Priority: Implement Processes for Sustained Cross-Sector Coordination

Whether through the SHIP process, public health transformation, pandemic response, or ongoing partnerships on public health challenges such as the opioid crisis, states have built relationships and infrastructure to communicate and collaborate with health care systems and other key partners on health priorities. Mobilized by the “all hands on deck” nature of the COVID-19 emergency response, states were forced to think beyond antiquated and siloed communication strategies to rapidly exchange information across public health, health care, and community partners and develop real-time responses to limit outbreaks, respond to surging demands on the health care system, and mitigate risks for medically underserved communities.

Sustaining these efforts beyond the public health emergency and applying lessons learned to addressing ongoing health challenges requires sustained funding and focus, as well as consistent efforts to reduce operational silos, facilitate bi-directional dialogue and exchange, and overcome logistical and cultural barriers that inhibit coordination. The following are strategies that states have used to support greater exchange and communication across public and private sectors, as well as examples of how states adapted innovations borne of the COVID-19 pandemic to address other public health challenges.

State Strategy: Address Barriers to Communication and Collaboration

Building relationships with partners from different sectors or disciplines with different missions, priorities, cultures, and capacities requires intentionality. Many states described a lack of understanding or need for “translation” across public health and health care system partners as a primary challenge to collaboration, along with often overlapping but distinct missions and business models.

States are pursuing several strategies for building relationships and communications channels across sectors, including establishing formal mechanisms for collaboration and communication and creating opportunities for private sector experts to temporarily deploy to support public sector policy efforts. Some promising examples include:

- Michigan is creating the infrastructure to sustain long-term relationships across health care system partners by organizing quarterly grand rounds focused on infectious diseases. Each meeting will include presentations from state and local health departments, as well as clinicians, with a broad focus on any issues relating to infectious diseases. These grand rounds are meant for non-urgent emerging issues, but this existing infrastructure can also be used to call emergency meetings when time-sensitive issues emerge, such as with COVID-19.

- The Connecticut Department of Public Health (DPH) was able to bolster capacity in its Epidemiology and Emerging Infections Program by funding the co-appointment of an infectious disease expert at the Yale School of Public Health through a DPH-CDC cooperative agreement. Such arrangements create opportunities for public health agencies to leverage additional clinical and academic expertise and build relationships across these entities, provided that such agreements are carefully designed to promote mutual goals while avoiding confidentiality issues and conflicts of interest. Such a model could function through other funding streams and be expanded to support a network of states.

- To more effectively engage private sector resources and expertise in the COVID-19 vaccination effort, the Washington State Department of Health stood up the Vaccine Action Command and Coordination System (VACCS) Center, which provided a single point of contact and coordination for engaging over 50 partners from across the state to support an efficient and equitable vaccine rollout. By effectively partnering with Washington companies such as Starbucks and Microsoft, the VACCS Center was able to rapidly deploy tools such as a Vaccinate WA’s vaccine appointment scheduling tool and a COVID-19 assistance call center, coordinate free transportation to appointments, and improve upon processes such as supply logistics and vaccination site efficiencies.

Resources

- Frameworks Institute: Strategies for Communicating Effectively about Public Health and Cross-Sector Collaboration with Professionals from Other Sectors

- Frameworks Institute: Public Health Reaching Across Sectors: Mapping the Gaps between How Public Health Experts and Leaders in Other Sectors View Public Health and Cross-Sector Collaboration

- Public Health Reaching Across Sectors: Resources and Expertise to Impact Public Health

State Strategy: Leverage and Scale Effective Approaches for Cross-Sector Coordination from the COVID-19 Pandemic

To support a coordinated public health response during the COVID-19 pandemic, states stood up interagency and multi-sector task forces, instituted regular webinars or calls to communicate and hear from health sector partners, and expanded the reach of partnerships with community groups, schools, daycares, businesses, and other sectors impacted by the pandemic. Through these collaborations, states were able to provide critical resources and expand access to vaccination, testing, and treatment services for communities that have traditionally been disconnected from public health services.

States can build upon relationships and successful models established during the pandemic and work to apply innovative strategies to address other disease conditions. Many of the successes of the COVID-19 community-based vaccination efforts are already being applied in other contexts such as with mpox (previously called monkeypox) vaccination campaigns targeted to populations at highest risk. Without these previously established relationships, state officials may have had more difficulty in reaching at-risk populations that have faced stigma in traditional health care settings. Similarly, strategies and partnerships with provider associations and health care systems to dispel vaccine myths and disinformation continue to be applied to improve confidence in COVID-19 and routine immunizations. For example, the Maryland Department of Health (MDH) supported primary care practices through data that enabled targeted outreach to unvaccinated patients, coordinated resource distribution and regular communication between MDH and practices, and financial support. Beneficiaries in the Maryland Primary Care Program experienced lower case rates, hospitalizations, and a 27 percent lower COVID-19-attributed death rate.

While states described a decreased frequency of regular partner communications as the pandemic slowed, they also noted that many task forces and calls have continued and expanded to emerging issues. In Minnesota, weekly dedicated COVID-19 teleconferences between the Department of Health and infectious disease physicians have transitioned to monthly opportunities for the state to communicate updates and solicit clinician feedback on a variety of COVID-19 and non-COVID-19 infectious issues. Leaders from the state National Guard, government agencies, health care systems, education institutions and associations, nonprofit and non-governmental organizations, and public health officials convened by the West Virginia Joint Interagency Task Force are now focusing on leveraging lessons learned from COVID-19 to address health challenges across the state. Brown University’s State and Territorial Alliance for Testing network, originally formed to expand state purchasing power for COVID-19 testing supplies, has evolved to support a regular exchange of information around ongoing health challenges across public health and education.

Key Priority: Improve Exchange and Accessibility of Public Health Data

The COVID-19 pandemic pressure-tested antiquated data systems and revealed a system badly in need of investment, vision, and coordination, which the Healthcare Information Management Systems Society anticipates will cost $37 billion to modernize. The lack of interoperability and data sharing, however, isn’t always about lack of infrastructure and technology. It’s also about trust, stewardship, and ownership. Understanding the individual needs, challenges, and impact of potential changes on public health and health care systems alike can help prioritize limited resources, avoid unintended consequences, and break down various barriers to implementation.

While the federal government continues to advance broad-scale initiatives to improve public health data systems and exchange of health information across health care partners (see Federal Efforts to Improve Public Health Data Systems), states have opportunities to leverage federal investments to make more immediate infrastructure improvements, while also bringing critical partners together to address logistical, technological, or coordination challenges that might hinder information-sharing between public health, Medicaid, and other key health care system partners on common priorities. Seamless, bi-directional exchange of data across public health and health care system partners will be critical to achieving a “system-wide environment of innovation” capable of both responding to emerging threats and improving community health (see Envisioning a 21st Century Surveillance System). Working toward a unified, shared governance approach and improving data exchange with health care system and community partners in the near term is also necessary for driving collaborative, data-informed interventions on public health priorities.

Federal Efforts to Improve Public Health Data Systems

Understanding the role of the federal government and its efforts to promote data interoperability across health system partners (including public health data and surveillance systems) can help states prioritize strategies and investments to promote the exchange of real-time linked data between public health and health system partners that can support timely public health responses to emerging threats.

- The 2020–2025 Federal Health IT Strategic Plan from the Office of the National Coordinator for Health Information Technology (ONC) includes goals to advance individual and population-level transfer of health data and support research and analysis of that data. The plan promotes interoperability of electronic health information, makes it possible to exchange large datasets for use in research, and supports a common agreement for nationwide exchange of health information that supports federal strategies and promotes effective governance.

- The CDC’s Data Modernization Initiative (DMI), launched in 2020, is a multi-year investment of more than $1 billion to modernize core public health data and surveillance infrastructure. DMI priorities include the strengthening and unifying of critical infrastructure; accelerating data into action to improve decision-making and protect health; developing a state-of-the-art health IT, data science, and cybersecurity workforce; supporting and extending partnerships; and managing change and governance.

- As part of the DMI, the CDC and ONC are developing the North Star Architecture, a cloud-based platform for public health data-sharing. Through a joint governance model, the North Star Architecture is intended to provide a flexible range of supports to state and local public health jurisdictions through a common platform and shared infrastructure, tools, applications, and data repositories that will allow state and local jurisdictions to remain in control of their data.

State Strategy: Engage Health Care Partners in Identifying and Addressing Gaps in Data-Sharing

To effectively leverage disconnected data sets to respond to the immediate demands of the COVID-19 response, states raced to fill immediate data interoperability gaps through strategies such as moving to cloud-based systems, automating manual reporting processes, and establishing data lakes that could support linkage of bulk data sets. States have also continued to make investments in data capacity, exchange, and analytics across the U.S. Public Health Surveillance Enterprise Core Data Systems, including syndromic surveillance, electronic case reporting, notifiable diseases, electronic laboratory reporting, and vital records.

Envisioning a 21st Century Surveillance System

In 2020, a group of state and territorial health agency leaders convened by the Association for State and Territorial Health Officials (ASTHO) identified a core set of priorities for building a 21st century public health surveillance system that:

- Coordinated policies, consensus-based standards, and decision-making across states, CDC, and federal partners to develop interoperable systems that allow for efficient data exchange.

- Developed enterprise-level information technology and data infrastructure that supports cloud-based platforms and real-time data automation.

- Enabled a system-wide environment of innovation among new public-private partnerships with health care providers, technology companies, and other entities to create new tools that empower communities, patients, and consumers.

As states pursue additional opportunities to improve bi-directional data exchange with health care systems, engaging with health care systems, payers and other health care system partners is critical. With the right leadership and invested partners involved from the beginning, states may prioritize modernization projects according to criteria such as cost, impact, and urgency of the challenge, as well as the potential feasibility and return on investment. In developing strategic priorities for improving public health information exchange across key partners, some key steps include:

- Engage partners in identifying challenges, priorities, and solutions: Bringing all partners to the table — public health, Medicaid programs, health and human services systems, community-based organizations, information technology experts — and keeping their priorities in mind when negotiating the terms of data-sharing and governance agreements can help to move the process in a positive direction.

- Build on existing data infrastructure: States have developed unique infrastructures that allow for secure exchange of health information across authorized public health agencies, public and private payers, providers, hospitals, and electronic health record (EHR) systems. Data exchange infrastructure such as state and regional health information exchanges, all-payer claims databases, and Medicaid data warehouses can be augmented to better support information exchange across key partners and provide state health leadership with data to inform population and public health interventions.

- Assess gaps and build capacity: The CDC’s Data Modernization Initiative Strategic Implementation Plan outlines five key priorities for developing a “connected, resilient, adaptable, and sustainable ‘response-ready’ system.” Through investments provided by the American Rescue Plan and CARES Act, many states have already taken steps to identify data modernization leads, conduct gap assessments, and implement data modernization plans.

CDC Data Modernization Initiative: Five Key Priorities

- Build the Right Foundation: Strengthen and Unify Critical Infrastructure for a Response-Ready Public Health Ecosystem

- Accelerate Data into Action to Improve Decision-Making and Protect Public Health

- Develop a State-of-the Art Workforce

- Support and Extend Partnerships

- Manage Change and Governance to Support New Ways of Thinking and Working

In its Data Modernization Initiative Project Planning, Washington state has taken initial steps to improve its data infrastructure through alignment of internal structures, assessment of gaps in its data ecosystem, and plan development. To address the more than 50 different surveillance data systems (with duplicative data structures, formats, standards, and legacy processes and protocols), Washington contracted with the University of Washington to conduct an assessment and gap analysis of the state’s infrastructure, systems, and workforce. Resulting recommendations will drive modernization efforts over the next five years, with an emphasis on shared vision, efficiently transitioning away from siloed systems.

Resources

- Creating an Interoperable and Modern Data and Technology Infrastructure, Lights, Camera, Action: The Future of Public Health National Summit Series: Summit 2

- CDC: Public Health Data Modernization Initiative

- CSTE Driving Public Health in the Fast Lane: The Urgent Need for a 21st Century Data Superhighway

- PHII: Data Modernization Planning Toolkit

- Network for Public Health Law: Checklist of Information Needed to Address Proposed Data Collection, Access, and Sharing

- ASTHO Data Linkage Webinar Series

- Data Across Sectors for Health (DASH): Advancing Community Health Through Equitable Data Systems

- All In: Data for Community Health

State Strategy: Improve System-Wide Visibility on Public Health Challenges and Progress

The COVID-19 pandemic has demonstrated the importance of providing the public with data that can be used to make informed personal, organizational, and population-based decisions. Health departments, universities, government agencies, and others have produced and published publicly available dashboards that have informed about COVID-19 case, hospitalization, and death rates on local, state, national, and international levels, and they have relied on those sites to communicate important and timely information to the public vaccine and treatment availability. Dashboards can also provide visualization of health disparities, and states have made significant improvements in capturing demographic data that can help provide a clearer picture of what those disparities look like and which populations are most impacted by them.

- New Jersey Department of Health is using lessons learned around the need for rapid data access and reporting to build the Department of Health’s Centralized Data and Analytics Hub, a growing repository of data collected from within and outside of government and shared with partners to drive public health decisions.

- Virginia Department of Health publishes online dashboards on a number of topics, including communicable diseases, drug overdoses, and maternal-child health. The communicable diseases dashboard includes trends of the top 10 communicable diseases over time, incidence of those diseases by state region, and the rates of those diseases per 100,000 population.

- North Dakota Health publishes online dashboards on Alzheimer’s mortality (by county), communicable diseases, immunization rates, opioids, and other conditions. The Alzheimer’s dashboard projects Alzheimer-related Medicare claims through 2040.

- California Department of Public Health’s Maternal, Child, and Adolescent Health Division publishes indicator-specific dashboards organized according to Title V health domains, including dashboards on women, infants, children, children and youth with special health care needs, and adolescents.

- Hawaii Department of Health and the Hawaii Health Data Warehouse partnered to develop a website that provides state and county level data on a variety of topics, including chronic conditions, health behaviors, behavioral health, and health care access and quality. The site also allows users to build custom dashboards based on location, population, topic, and other criteria.

Key Priority: Strengthen Collaboration between Medicaid and Public Health

Public health, state Medicaid programs, and health care partners share common goals of improving health outcomes for people with complex, and often high-cost, health conditions such as heart disease, diabetes, asthma, chronic communicable diseases, and other chronic diseases. This common mission is accompanied by goals for good stewardship of resources and incentivizing cost-effective approaches across health care purchasers, including public payers/funders and the commercial market. While public health and health care business models diverge, aligning and leveraging expertise toward common public health goals at points of intersection can help drive investments upstream. State policymakers have a range of options to leverage these intersection points and shape policy, delivery, and purchasing approaches across state agencies and incentivize health care system partners to invest in improving public health.

Building linkages and collaboration across public health and state Medicaid programs is a particularly powerful tool for mounting effective strategies to address high-burden, high-cost health conditions. Covering over 80 million individuals across the U.S., Medicaid and CHIP programs can leverage purchasing power, MCO contracting, and provider requirements to drive improvements across key health priorities in collaboration with public health agencies. The following are strategies to increase collaboration and align financing approaches between Medicaid and public health.

State Strategy: Address Funding and Operational Silos across Public Health and Medicaid

Fragmented funding streams are a mainstay in the U.S. health care and public health systems, with siloed federal funding streams (and associated accountability requirements) flowing to various state agencies and local partners. These funding recipients are poorly aligned with public and private health insurance programs that operate under a reimbursement approach. Within states themselves, Medicaid programs and public health agencies can function in funding and operational siloes, with little coordination on policies or resource allocation across public/population health-level efforts and clinical care delivered at the individual level. To leverage resources more effectively at the intersection of public health and the health care system, many states are taking steps to review the funding streams currently available to them, reorganize current program structures, and establish processes to bring various public and/or private funding streams together. High-burden health conditions with strong evidence-based intervention lend themselves to public health and health care collaborations. Through participation in the CDC’s 6|18 Initiative, many states implemented successful strategies for health care providers, public health, insurers, and employers who purchase insurance to collaborate on proven interventions to reduce tobacco use, control blood pressure, reign in antibiotic use, control asthma, prevent unintended pregnancy, and prevent type 2 diabetes.

With a shared mission to improve health outcomes for underserved, high disease-burden individuals and communities, state Medicaid programs and public health agencies’ increased collaboration at the leadership and operational levels can support data-driven interventions that efficiently leverage the whole of the health care system to address the key drivers of cost and mortality. Examples of efforts to break down barriers across Medicaid and public health include:

- Missouri’s Asthma Prevention and Control Program in the Department of Health and Senior Services partnered with MO HealthNet (the state Medicaid Agency) to reimburse for asthma in-home assessment and education visits.

- Maryland’s Medicaid agency collaborated with the Environmental Health Bureau and the Department of Housing and Community Development to secure CHIP administrative funds in support of environmental case management and in-home education programs to reduce the impact of asthma and lead poisoning in children enrolled in Medicaid or CHIP.

- Although the cornerstone of Louisiana’s “Hep C Free Louisiana” is a “modified subscription model” that caps spending on direct-acting antivirals for treatment of hepatitis C for Medicaid-enrolled and incarcerated individuals, the state’s hepatitis C elimination plan seeks to align resources and efforts across agencies, payers, and other partners to expand screening for priority populations, promote prevention, improve surveillance, and expand access to services. Within the Department of Health, Medicaid and the Office of Public Health leveraged public health resources to support the hepatitis C elimination plan through provider trainings, public awareness campaigns, direct outreach, screening activities, and collaborations with syringe service programs.

State Strategy: Strengthen Information Exchange between Medicaid and Public Health

The matching of data between public health databases and Medicaid claims can be a powerful strategy for both shaping population health initiatives and working with MCOs and providers to identify populations that could benefit from targeted outreach. Data can also be used to monitor the impact of interventions and may guide efforts around continuous quality improvement.

Data-sharing between Medicaid (and its managed care partners), immunization programs, and providers to support resource allocation and targeted outreach efforts for COVID-19 vaccination has been one of the most successful and widely adopted examples of cross-agency data exchange. Many state immunization programs have entered into agreements with their state’s Medicaid agency to match immunization administration data housed in the immunization information systems (IIS) with Medicaid claims data. This collaboration has resulted in more complete IIS data (including race and ethnicity information that may have otherwise been incomplete) and the ability of Medicaid programs to provide outreach to unvaccinated individuals. Here are a few examples:

- Minnesota created a data-sharing arrangement between its immunization program and the state’s 10 largest EHR systems, resulting in more complete data collection, reducing duplicate data entry, and providing immunization forecasting to providers to reduce missed opportunities to provide vaccinations.

- To support more accurate reporting of vaccine coverage rates to CMS, the North Dakota Department of Health executed a data use agreement with its Medicaid office that enables sharing of IIS and Medicaid data to calculate immunization coverage rates for children insured by Medicaid and compare them with immunization coverage rates of children who are privately insured.

There are numerous examples of how alignment of data across public health and Medicaid systems has informed interventions to address public health challenges that are also major cost-drivers to the Medicaid program. Some examples include:

- Improving outreach and care for individuals with HIV: Medicaid programs and MCOs often lack sufficient information from claims to identify individuals who have tested positive for HIV but who may not be receiving adequate treatment services. Because HIV and other infectious diseases such as hepatitis C are reportable conditions, this information is housed in state surveillance systems. Better integration of Medicaid and surveillance systems can provide public health, Medicaid, and providers with a more complete picture of populations that may benefit from improved access to treatment, as well as support quality improvement programs and targeted efforts to connect individuals covered by the Medicaid program to health care. With measures of HIV viral load suppression included in the Medicaid Adult Core Measure Set, a number of states have made efforts to support data-sharing across Medicaid and state surveillance systems to enable more robust reporting. In Louisiana, the Medicaid program implemented a quality measure that requires MCOs to report the percentage of patients with a diagnosis of HIV and a viral load below a threshold of 200 copies/ml. Medicaid MCOs use data provided by the state’s Office of Public Health to identify members who have not achieved viral suppression. The MCOs’ regional clinical practice consultants work with clinicians caring for those patients, connecting them to resources that can help their patients achieve viral suppression.

- Addressing infant and maternal mortality: In partnership with a data analytics company, Indiana identified 22 datasets (vital statistics, immunization information system, birth defects registry, newborn screening program, Medicaid claims, and others) from a range of agencies and programs to identify risk factors driving the state’s infant mortality rate. Of those datasets, nine were determined to hold predictive power to drive intervention. An advanced data analytics platform was created to securely store data that was accessible to analysts across agencies within and outside of state government. Using machine learning, the state created a predictive tool to calculate the risk of infant mortality for certain geographic areas and subpopulations and tailored programming to provide education and prenatal care in at-risk areas.

Building the Data Infrastructure for Medicaid and Commercial Payer Alignment on Shared Priorities

As purchasers of health care for over 88 million Americans, state Medicaid programs play an important role in shaping health policies and priorities within states. However, with over half of the population enrolled in employer-based or non-group insurance, states can also look to engage commercial payers and state health plans to widen the reach and impact of initiatives to advance state health priorities. Through North Carolina’s Medicaid transformation efforts, the state has prioritized building a sustainable infrastructure that can support continued alignment and engagement of commercial payers in the goals of the state’s health care transformation efforts. Although North Carolina’s Section 1115 Medicaid Demonstration waiver provides for specific coverage of several categories of health-related social needs for Medicaid enrollees, the state also has encouraged and facilitated coordination among providers and other payers to coordinate with social service providers to address a common set of health-related social needs.

Like many states and local jurisdictions, North Carolina uses a statewide closed-loop referral system, NCCARE360, to connect clinical providers with community-based organizations and other social service providers and to connect social service providers to each other. The platform is supported by public and private funding and is free for providers and CBOs to use. To support connectivity of these efforts across agencies, providers, and payers, the state developed standardized screening questions focused on individuals’ social needs, which MCOs are required (and providers and commercial payers are encouraged) to use. The state uses a variety of data feeds to interpret the screening results and is undertaking steps to connect with the state’s health information exchange to further build out the data infrastructure. In the absence of this state coordination, it is likely that different payers and communities would have developed their own social needs assessments and technology platforms, with limited consistency or connectivity across systems.

To ensure long-term sustainability of the system, NCCARE360 is a public-private partnership between the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services and the Foundation for Health Leadership and Innovation (FHLI). FHLI administers the system and holds the contract with NCCARE360 implementation partners: United Way, UniteUs, and Expound. Initially supported solely through philanthropic funding, NCCARE360 is now using a combination of Medicaid dollars, federal COVID-19 funding (e.g., CARES Act), and other federal grant dollars, including the CDC Health Equity grant and a preschool developmental grant. As the platform becomes more robust and shows value to providers, it is expected that health systems will also contribute to its funding. Through this gradual shift, the state has encouraged all private and public health plans to adopt NCCARE360 and share this foundational tool.

State Strategy: Incentivize Medicaid MCOs and Providers to Improve Population Health Outcomes

Many states rely on Medicaid MCOs for the delivery of health care for Medicaid enrollees, and contractual agreements with MCO partners are an important vehicle for achieving desired health outcomes. Working closely with public health leaders, Medicaid programs can promote state public health goals by ensuring access to a full range of services to support chronic disease prevention, detection, and interventions; reduce the spread of infectious diseases; and address preventable causes of death and injury, such as accidental drug overdoses and maternal mortality. State Medicaid programs can work in partnership with public health agencies to identify population health priorities and incentivize MCOs to improve associated outcomes among their enrollees.

A key strategy states are using to improve population health outcomes is the establishment of benchmarks and quality incentives that encourage providers and MCOs to undertake certain activities or achieve population health targets. Medicaid programs can establish incentive payments for MCOs that perform above certain quality benchmarks. For example:

- In New York, multiple partners, including the New York State Department of Health’s (NYSDOH’s) AIDS Institute, the state Medicaid agency, and MCOs, worked collaboratively to improve quality of care for people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA). In alignment with a state public health department’s roadmap to end the AIDS epidemic, Medicaid added HIV-specific metrics to MCO contract requirements aimed at reducing patient viral load and ensuring treatment is provided to individuals testing above certain viral load thresholds. The AIDS Institute receives a list of members enrolled in each health plan who have data in the NYSDOH HIV surveillance system and who have Medicaid claims and shares a list of members who have not achieved viral suppression with health plans to ensure these members receive adequate treatment. Health plans that perform exceptionally well on these metrics are eligible to receive an incentive payment of up to 3 percent added to their negotiated payment rates. Plans are compared to their peers and awarded points for performing above the 50th, 75th, or 90th percentiles; points awarded to each plan determine their incentive payments. These efforts have led to improvements in the quality of care for PLWHA, and viral load suppression rates have increased over time.

- In partnership with public health and state partners in the executive branch, the Michigan Medicaid program established a temporary bonus pool to support vaccinating providers and reward the health plans that reached certain benchmarks for COVID-19 vaccinations. Benchmarks were set based on milestones in Governor Gretchen Whitmer’s “MI Vacc to Normal” plan, which aimed to vaccinate 70 percent of state residents age 16 and older. Medicaid health plans that vaccinated 55 percent of their members were eligible to receive a 30 percent share of bonus pool funding, and plans that vaccinated 70 percent of that population were eligible to receive a 100 percent share of funding. If a plan did not meet either benchmark, its share of funding was returned to the pool for distribution to plans that met benchmarks.

Endnotes

[1] These estimates do not account for funding needed to update information technology systems.

[2] Through the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Innovation’s State Innovation Model demonstration projects in 2013 and 2014, 38 states have worked to develop and test strategies to accelerate health care transformation.

You are viewing one section of the Public Health Modernization Toolkit. Please check out the other two sections: