State policymakers are presented with a unique set of challenges when addressing the provision of behavioral health crisis services in rural areas, including:

- Higher rates of unmet behavioral health needs

- Higher (and increasing) suicide rates

- Severe behavioral health workforce and resource shortages

- Longer distances between providers and patients

- Stigma

To assist states in their work to improve rural behavioral health crisis services, NASHP hosted a 12-month State Policy Academy on Rural Mental Health Crisis Services with five state teams selected through a competitive application process (Montana, South Carolina, South Dakota, Texas, and Wisconsin). State teams were composed of leaders in Medicaid, behavioral health agencies, rural health agencies, and other state officials involved in advancing cross-agency approaches.

The policy academy included technical assistance through multi-state convenings, individual state support, and best practices shared by subject matter experts in the field. Federal action on the national 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline as well as the enhanced Medicaid reimbursement rate for mobile crisis services informed state policies and financing strategies.

The Rural Behavioral Health Crisis Continuum: Considerations and Emerging State Strategies

Policy Academy Lessons, Successes, and Next Steps

Lessons learned by the participating states along with successes and ongoing challenges are summarized below and may provide insight to other states seeking to improve the behavioral health crisis care continuum in their rural areas.

Prioritizing Data-Informed Strategies

- South Dakota conducted a statewide needs assessment to identify the gaps and opportunities for reform in their rural behavioral health crisis continuum. They used these findings to inform their focus on telehealth, 988 implementation, and mobile crisis services in rural areas.

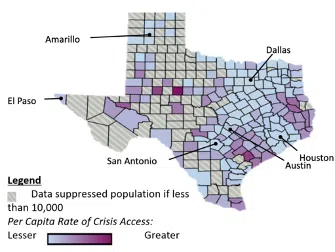

- Texas completed an in-depth data review on mental health crisis service utilization across the state. Between 2017 and 2021, people in rural areas were accessing crisis services significantly more on a per capita basis than those in urban areas. Rural youth (under 18 years old) accessed crisis services 150 percent more than urban youth, and rural adults (18 years and older) accessed crisis services 45 percent more than urban adults. The findings from this data review led the Texas Health and Human Services Commission to create a community engagement pilot project in three areas of the state with above average crisis utilization. The pilot project includes focus groups and interviews with community stakeholders, a community member survey, and research into the social determinants of health in these communities.

Source: All Texas Access Report, Texas Health and Human Services

- Wisconsin surveyed county-level crisis administrators throughout the state, finding notable interest in enhancing mobile behavioral health crisis responses and associated challenges securing staffing for such teams. In response, the team has redesigned Medicaid billing codes to reflect and differentiate components of the full continuum of crisis response modeled on the Crisis Now framework — adding the option to use a mobile crisis teaming response, expanding the provider types that can be reimbursed by Medicaid, and including three new billing codes (for crisis line services, for crisis response service, and for crisis linkage and follow-up to complement existing codes for stabilization services). This differentiated billing approach also provides more granular data for continuous improvement and tracking regional variation.

Advancing Cross-State and Key Stakeholder Partnerships

- The South Carolina Department of Mental Health (DMH) and the South Carolina Office of Rural Health (SCORH) strengthened their partnership around a set of concrete goals to expand access to crisis services in rural South Carolina. DMH and SCORH established routine meetings to exchange information and opportunities for collaboration. Examples of ongoing collaborations include:

- Highway to Hope. All 16 community mental health centers in South Carolina (which cover the 46 counties) are currently rolling out mobile mental health clinics to increase physical access, in addition to virtual options in some of the more remote locations in their service areas.

- SAMHSA Cooperative Agreements for Innovative Community Crisis Response Partnerships in 10 rural counties. As part of a Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) funding opportunity for Community Crisis Response Partnerships, DMH received a grant of $3 million to expand mobile crisis services in 10 rural high-need counties. Investments include $750,000 annually for four years to expand DMH’s existing mobile crisis program by adding certified peer support specialists to co-respond with master-level clinicians to individuals experiencing a mental health crisis and provide follow-up. In addition, at least one law enforcement agency in each of the 10 counties will receive funding for tablets and data service plans, which will increase law enforcement’s options for including mental health professionals when they respond to incidents with mental health components.

- Following the award of a 988 Planning Grant from SAMHSA, South Dakota policymakers formed the Behavioral Health Crisis Response Stakeholder Coalition (BHCRSC) in February 2021 to discuss implementation efforts of the 988 hotline and additional planning around mobile crisis services. The coalition includes individuals with lived experience, crisis center representatives, state suicide prevention coordinators, mobile crisis service providers, peer support providers, advocacy group leaders, 911 workers, and law enforcement. Coalition focus areas include developing crisis response strategies, 988 marketing and communication, and needed statute and policy review. Going forward, the the coalition plans to address the need to foster more local, in-person providers in rural areas and build more sustainable funding for the crisis continuum with the help of the two-year, SD 988: Building Local Capacity Grant.

- Texas plans to leverage its new team dedicated to rural behavioral health to collaborate with select communities in eastern and southern regions of the state to share data and identify causal variables and associated strategies to differential crisis service utilization across the regions. In addition, the team will aim to connect rural Texans with regional and statewide behavioral health providers, link rural behavioral health providers with local and national expertise, develop relationships across different types of behavioral health providers, elevate the perspective of rural behavioral health providers to state policymakers, and continue the work of the All Texas Access Initiative (a legislative mandate for the Health and Human Services Commission to partner with rural authorities to increase access to behavioral health services).

Identifying and Implementing Financing/Funding Approaches

- South Dakota applied for the SAMHSA Innovative Community Crisis Response Partnerships cooperative agreement. Though South Dakota was not awarded the cooperative agreement, the state leveraged the application planning process and SAMHSA allocated one-time funding to South Dakota’s Department of Social Services in the amount of $131,592 to pilot mobile crisis response strategies adapted for rural and frontier settings. The pilot builds capacity for dedicated trained crisis care case managers employed by two community mental health centers in the state’s rural regions. Notably, South Dakotans recently voted for Medicaid expansion to begin in July 2023 in their state. State policymakers are considering how to leverage the expansion of Medicaid eligibility in support of South Dakota’s behavioral health crisis continuum.

- The Wisconsin Division of Medicaid Services received a one-year planning grant from the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) to develop an enhanced, sustainable, mobile crisis teaming model. Wisconsin is finalizing an update to its Medicaid state plan amendment (SPA) to support the provision of behavioral health services, including crisis hotlines. In addition, the state will focus on securing long-term, sustainable funding for the new 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline to enhance early intervention opportunities and decrease unnecessary use of emergency rooms, law enforcement, and more restrictive settings such as hospitals and jails during behavioral health crisis situations.

- South Carolina DMH and the State’s Medicaid agency, the South Carolina Department of Health and Human Services, are collaborating to use state funds to increase the number of crisis stabilization units.

Bolstering the Workforce

- South Carolina DMH is approaching workforce development through pipeline, scholarships/internships, and hiring and retention approaches. The state has multiple collaborations with South Carolina technical colleges and universities to build the pipeline and certification programs. The DMH deputy director for community mental health services meets quarterly with the training directors in social work and counseling from these institutions to develop and grow partnerships, including the behavioral health technician certification program and the University of South Carolina school mental health services internship. The agency is offering paid internships for nursing, social work, counseling, and psychology and has started an accredited Forensic Psychology Fellowship. The state is also supporting a new psychiatric residency program in Orangeburg. The state notes that the biggest challenge to building an adequate behavioral health workforce is building capacity to pay competitive salaries.

- Texas is launching a learning collaborative focused on increasing the hiring and retention of peer specialists in rural-serving local mental health authorities (LMHAs). Achara Consulting, an organization of national experts on peer support, will meet with participating LMHAs via site visits, webinars, topical calls, and individual consultations for the LMHAs.

- Wisconsin will soon introduce a Medicaid policy that allows counties to bill for certified peer specialists that perform crisis interventions as a part of a multi-pronged effort to reduce the workforce challenges in rural counties.

Leveraging Telehealth

- The South Dakota Department of Health partnered with Avel eCare to implement Telemedicine in Motion for emergency medical services (EMS). This project is the result of policymakers investing $1.7 million (of the governor’s $20 million budget for EMS) to equip ambulances across the state with tablets for telehealth services. These tablets connect EMS directly to a licensed provider in South Dakota to assist them in responding to any emergency, ranging from physical trauma to behavioral health crises. South Dakota is excited for Telemedicine in Motion to expand behavioral health infrastructure in rural areas and support recruitment and retention of their EMS and behavioral health workforce.

- In January 2024, Wisconsin plans to transition to an enhanced mobile crisis teaming billing code that will allow emergency medical technicians in rural areas to connect with county-based behavioral health providers through telehealth devices. To address the lack of staffing in rural areas, Wisconsin will allow for partial staffing of mobile crisis services (i.e., less than 24-hour availability) to receive the enhanced payment.

- South Carolina has opted to continue to reimburse behavioral health crisis services delivered via telehealth given its critical role as a workforce extender in providing crisis services in rural areas.

Relevant NASHP Resources

During the policy academy on rural behavioral health services, NASHP created a series of resources for states, some of which were published. Below are summaries and links to NASHP’s recent public-facing products on behavioral health crisis services, including in rural areas.

Enhanced Medicaid Funding for Mobile Crisis Teams

In December 2021, CMS issued guidance for state officials on how to draw down an enhanced 85% federal medical assistance percentage (FMAP) for mobile crisis services. This enhanced FMAP for mobile crisis was authorized by the American Rescue Plan Act.

See NASHP’s resource Mobile Crisis: Maximizing New Medicaid Opportunities for more information.

Network Adequacy Standards for Behavioral Health in Medicaid Managed Care

In general, states prioritize three key aspects of network adequacy in their Medicaid managed care contracts: service access requirements, provider network requirements, and telehealth utilization.

See NASHP’s resource Map: State Medicaid Managed Care and Access to Rural Behavioral Health Services for more information.

The Role of Peers across the Behavioral Health Crisis Continuum

States have different approaches to incentivizing integration of Medicaid coverage for peer services across the behavioral health crisis continuum, which includes call centers, mobile crisis teams, crisis stabilization units, and follow-up care. To support funding for peers, states have leveraged federal grants like the Community Mental Health Services Block Grant and their Medicaid SPAs.

See NASHP’s resource States’ Use of Peers in the Mental Health Crisis Continuum for more information.

State Legislation to Implement the National 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline

In July 2022, the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline replaced the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline (1-800-273-TALK). To prepare for the anticipated increase in demand of 988, many state legislatures passed 988-related legislation including provisions for telecommunications fees, general fund appropriations, and the establishment of advisory committees.

See NASHP’s resource State Legislation to Fund and Implement the 988 Suicide and Crisis Lifeline for more information.

Future Directions for Rural Behavioral Health Crisis Services

Due to the unique challenges that rural areas face, policymakers and communities in these areas are innovating to bolster the behavioral health crisis continuum moving forward. Lessons from states that participated in NASHP’s policy academy and those described in the accompanying brief provide some paths forward.

In addition, federal support for modernized responses to behavioral health crises in rural areas will continue to be essential. State policymakers noted that advancing state polices and investments in the crisis care continuum would benefit from opportunities to braid federal grant funds targeting overlapping populations and outcomes (such as for people with co-occurring mental health and substance use crises). They also noted a need for technical assistance on aligning behavioral health strategies with broadband policies and resources.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of a financial assistance award under the National Organizations of State and Local Officials (NOSLO) cooperative agreement. The contents are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the U.S. Government. For more information, please visit HRSA.gov.